When the House Speaker Tried to Catechize the Pope

Mike Johnson's "biblical borders" theology meets Aquinas, Pope Leo XIV, and the ugly reality of American immigration enforcement

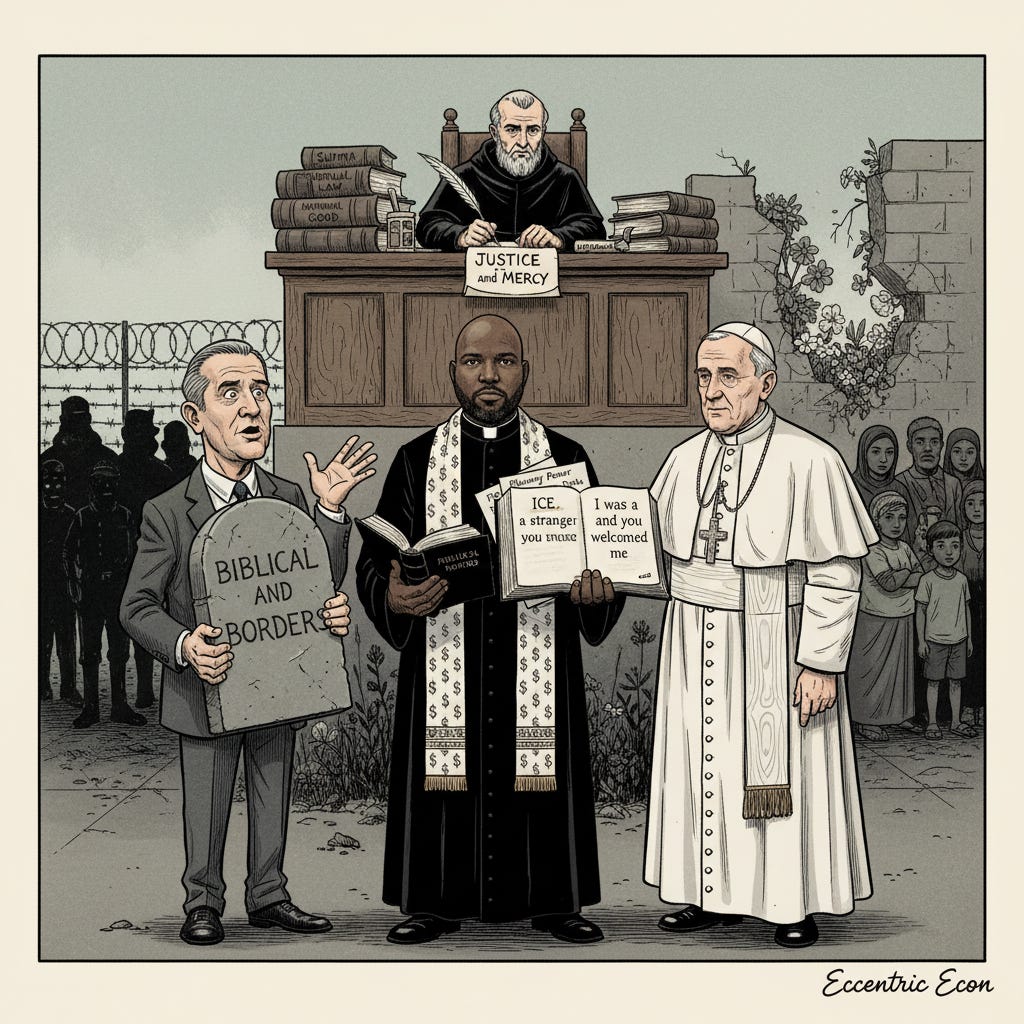

The House speaker of the United States has decided to explain the Bible to the bishop of Rome, and we are all expected to nod along as if this is a normal development in Christian theology rather than a live‑action Babylon Bee sketch. The good news is that Pope Leo XIV is right (oh, how it BURNS for me to admit this), Mike Johnson is wrong, and the actual Christian problem in American immigration policy is not a lack of walls, but a surplus of impunity—legal, bureaucratic, and theological.

When the Speaker Out‑Bibles the Pope

Johnson’s now‑infamous answer started when a reporter asked him about Leo’s criticism of U.S. immigration crackdowns; he responded with a genial smile and then launched into a theology lecture directed at the man Catholics call the Vicar of Christ. In that exchange, he assured the press that “sovereign borders are biblical and good and right” and that the state’s job is to “maintain the law,” not to get entangled in what he clearly sees as private virtues like mercy.

He has since expanded this into a full “Christian case for deportation,” complete with a “borders are biblical” riff and dark warnings that the pope and the “progressive Left” are twisting Scripture into a radical open‑borders agenda. The whole performance has been gleefully catalogued in pieces with headlines like “Mike Johnson Mansplains Religion to the Pope” and commentators accusing him of trying to “out‑Bible the Pope.“

Leo, by contrast, did something far less theatrical and far more threatening: he quoted Matthew 25’s “I was a stranger and you welcomed me,” asked for “deep reflection” on how migrants are treated, and called the mistreatment of immigrants a “grave crime.” He explicitly backed U.S. bishops who warned against “indiscriminate mass deportation” and “dehumanizing rhetoric,” framing these not as partisan issues but as questions of basic Christian faithfulness. When the pope says, in effect, “maybe don’t brutalize people,” and Washington hears “policy insurgency,” something is badly off.

Aquinas and the Stranger

If we are going to have a Bible fight, we might as well invite someone who actually did systematic theology. Enter Thomas Aquinas. In the Summa Theologiae, Aquinas famously insists that human law is law only insofar as it participates in natural law; when a statute departs from justice—when it systematically violates the claims of persons—it becomes a “perversion of law,” binding in fear but not in conscience.

For Aquinas, the “stranger” is not a spreadsheet category to place between “jobs” and “drugs.” Hospitality and care for the foreigner fall under misericordia—mercy—which he treats as a central component of charity, the virtue that orders our loves toward God and neighbor. The duty of mercy does not evaporate when someone picks up a gavel or a gun; the magistrate is not dispensed from the Gospel simply by being on payroll. The office does not launder cruelty into virtue.

Aquinas also understands that political communities have a right to self‑preservation and can regulate immigration prudently; his reading of Israel’s treatment of foreigners even emphasizes gradual incorporation. But for him, prudence sits beneath justice and charity, not above them. A polity can decide how to welcome; it cannot decide that welcoming is optional. On this point, Leo’s language about rights, duties, and the “grave crime” of mistreating migrants is far closer to Aquinas than Johnson’s neat separation of “state justice” and “private mercy.”

Leo XIV’s Quiet, Dangerous Orthodoxy

One of the more striking things about Leo XIV’s interventions on immigration is how un‑radical they are in Catholic terms. In interviews and addresses, he affirms that states have a right to regulate who enters and how—he talks about borders, procedures, and legitimate security concerns—but he refuses to treat migrants as raw material for national self‑assertion. His emphasis falls on two claims: that migrants possess “spiritual rights” that must be respected, and that nations will be judged on how they treat those who arrive vulnerable and dependent.

That is straight‑line Catholic social teaching: the universal destination of goods, the inherent dignity of the person, the priority of the poor. When Leo calls mistreatment of immigrants a “grave crime,” as he has done in remarks reported by Reuters, he is applying Matthew 25 at the level of peoples and institutions, not just individual consciences. The line between “you did it to me” and “you did it to them in my custody” is thinner than many Christian politicians want to admit.

Johnson’s response is to carve the Gospel up like a zoning map. In his comments, passages about welcoming the stranger are safely spiritualized, addressed to “individual believers,” while Romans 13 and assorted wall‑building texts are treated as the charter of the modern nation‑state. The result is a split personality Christianity: public order gets coercion and exclusion as its sacraments, while compassion is outsourced to churches and charities on the condition that they leave the policy architecture untouched. He is not misreading Leo here; he is rejecting the idea that mercy should ever become institutional design.

ICE, Plenary Power, and the American Gestapo

If this were just a matter of interpretive bravado, we could let the theologians fight it out over espresso in Rome. But the theology Johnson is defending has a body count and a line in the federal budget. In my own work—most recently in an SSRN piece, “ICE and the Plenary Power Problem: Extraconstitutional Authority and Interior Enforcement“—I argue that modern U.S. immigration enforcement, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement in particular, rests on a claim of near‑absolute “plenary power” over noncitizens. That doctrine places millions of people in a constitutional gray zone inside the country.

The structure is uglier than the euphemism suggests. Congress writes broad, often harsh statutes; the executive builds a sprawling interior‑enforcement machine with immense discretionary power; and politicians in both parties invoke “sovereignty” and “rule of law” to justify what happens in the shadows between statute and street. ICE operates in what I’ve called a “jurisdictional shadow”: embedded in American cities, but insulated from local democratic accountability, in ways that make abusive tactics and perverse incentives both likely and hard to correct.

In my essay bluntly titled “The American Gestapo Is a Budget Line,” I tried to make this concrete. Enforcement capacity—the number of agents, detention beds, and surveillance toys—grows because it is politically cheap: funding more “security” is easier than confronting the structure that rewards showy raids and high removal numbers over humane, targeted enforcement. As I put it there, and again in “Immigration and the New Color Bar,” we have decided to pay for a taste for exclusion with lower GDP, weaker communities, and a badly distorted sense of justice.

“Plenary power” is the Latin‑scented way of saying that when the federal government deals with noncitizens, especially at the intersection of borders and “national security,” normal constitutional restraints are loosened. When Johnson wraps this in biblical language—”borders are biblical,” “enforcing the law is righteous”—he is not just talking about fencing; he is offering theological cover to a legal regime built to keep one class of people just outside the circle of meaningful rights.

The Theology of Impunity

This is where Aquinas and Leo converge so uncomfortably for Johnson. Aquinas would see plenary power for what it is: a claim that some persons can be treated as means rather than ends in the name of public order. Once the law defines a neighbor as an “illegal,” the temptation is to treat whatever happens to them during “enforcement” as morally incidental—as long as the forms are signed and the box for “procedure followed” is checked.

Leo’s repeated insistence on migrants’ “spiritual rights,” and his willingness to call abuses at the border a “grave crime,” cuts directly across that habit of thought. In his language, sovereignty does not extend to redefining who counts as a neighbor. You may regulate entry; you may not rewrite the roster of the least of these. His call for “deep reflection” on immigration policy is not an invitation to convene a blue‑ribbon commission; it is a pointed question about whether our enforcement institutions have become occasions of structural sin.

Johnson’s theology, by contrast, is custom‑made for impunity. If mercy is not the state’s concern, then the moral evaluation of deportation policy stops at “was a law broken?” and “did the officer follow protocol?” If borders are “biblical” in a way that crowds out every other scriptural imperative, then any crack in the enforcement machine becomes a threat to godly order rather than an occasion for repentance and reform. The entire conversation shifts from “what is being done to these people in our name?” to “are we being tough enough?”

Aquinas will not let rulers off that easily. In his account, they sin not only by promulgating unjust laws but by tolerating unjust customs and institutions. If a practice predictably produces cruelty and disorders the souls of those who carry it out—if it trains officials to see certain bodies as less worthy of care—then the ruler who sustains that practice shares in its guilt, even when each individual act can be papered over with compliance reports and talking points.

The Economics of the New Color Bar

There is another irony that someone like Johnson, who likes to talk about “results,” ought to face: the moral panic driving his theology is built on economic assumptions that collapse on contact with the data. In “Immigration and the New Color Bar,” I argued that modern restrictionism functions like a race‑neutral version of the old color bar: a set of policies that constrict the labor force and slow growth in order to preserve a feeling of control for insiders.

Gary Becker taught us decades ago to treat discrimination as a “taste” that some actors are willing to pay for, and William H. Hutt showed how white unions in South Africa were happy to shrink industries to maintain their wage premia. In the same vein, contemporary immigration restriction is a national‑scale choice to accept slower GDP growth, demographic stagnation, and persistent skill shortages so that a political coalition can enjoy the psychic return of “keeping them out.”

When I surveyed the empirical literature for that piece, including work cited by the Dallas Fed, the pattern was clear enough: declining immigration is set to drag on U.S. growth, with only fleeting and modest gains for the workers restrictionists claim to protect. In Becker’s language, the country is paying more for the same output; in theological language, we are asking the “least of these” to underwrite our fears with their futures. Johnson’s “Christian” case for deportation, read in that light, looks less like moral seriousness and more like a sermon in praise of negative‑ROI sin.

A Thomistic Politics of Borders

So what would a more Thomistic politics of borders and enforcement look like? It would begin by rejecting the fake choice between “order” and “mercy.” For Aquinas, mercy is not justice’s sentimental opposite; it is justice’s perfection. A political community that refuses to see the humanity of those it punishes is not more just; it is less rational.

In practice, that implies at least three moves.

First, the state’s responsibility to maintain order includes an obligation to discipline its own agents. An ICE field office operating in a jurisdictional shadow with weak external checks is not an embodiment of Romans 13; it is an ongoing temptation to abuse—and therefore a failure of rulers to order the sword toward the common good. Building in independent investigations of deaths in custody, automatic public release of unedited body‑cam footage, and civil remedies that bite directly into agency budgets is not coddling lawbreakers; it is the bare minimum of Christian sobriety about power.

Second, the design of immigration law should reflect the reality of human lives rather than the convenience of enforcement metrics. Leo’s insistence that long‑settled migrants be treated with dignity recognizes that people sink roots—familial, economic, spiritual—into the places where they live. A regime that treats a father of U.S. citizens as a “case” to be closed with removal, twenty years after entry, is not simply enforcing rules; it is engaging in a kind of social vandalism that tears up communities for the sake of statistics.

Third, Christian politicians need to stop pretending that their hermeneutic is neutral. To read Scripture in a way that foregrounds Nehemiah’s wall and Romans 13 while relegating Matthew 25 to the realm of “personal spirituality” is a choice. It is a decision to treat certain texts as politically weighty and others as decorative. Aquinas—who never met a hierarchy of texts he didn’t want to organize—would at least insist on acknowledging when that ordering serves institutional agendas rather than simply falling from heaven.

The Stranger at the Hearing

The most honest test of Johnson’s theology is not a verse‑match with the pope; it is the fluorescent hearing room where a frightened mother listens as an interpreter explains that she is being deported to a country her U.S.‑born children have never seen. It is the funeral after a botched raid. It is the ICE detention facility that most voters could not locate on a map, whose conditions they prefer not to imagine.

In those moments, the question is not “are borders biblical?” but “what, exactly, are we doing to Christ’s ‘least of these’ under color of law?” Leo XIV has already given one answer by calling mistreatment of immigrants a “grave crime” and warning that nations will be judged on how they treat them. Aquinas, if you let him into the room, adds that rulers who willingly sustain institutions that reliably grind the vulnerable are not merely negligent; they are actively deforming the moral ecology of their people.

It is tempting, especially for those of us outside the Catholic Church, to treat papal statements as purely intra‑ecclesial affairs with little relevance to American constitutional structure. That is a mistake. The argument between Leo and Johnson is not about canon law; it is about whether mercy has any claim on the design of public institutions, or whether it must content itself with charity drives after the raids are over.

If you believe, as I do, that the Gospel has something to say about how we structure the agencies that carry guns in our name, then the choice on offer is not “biblical borders versus lawless compassion.” It is a choice between a politics that uses Scripture to sacralize impunity and a politics that treats immigrants—documented or not—as neighbors whose rights do not evaporate when someone says “sovereignty.”

On that choice, Aquinas, Leo XIV, and the available data all land in the same place: the pope is right, the speaker is wrong, and the real crisis at the border is not unauthorized entrants but an authorized theology of exclusion with a very stable funding stream.