The American Gestapo Is a Budget Line

ICE calls it self‑defense. The incentives say otherwise.

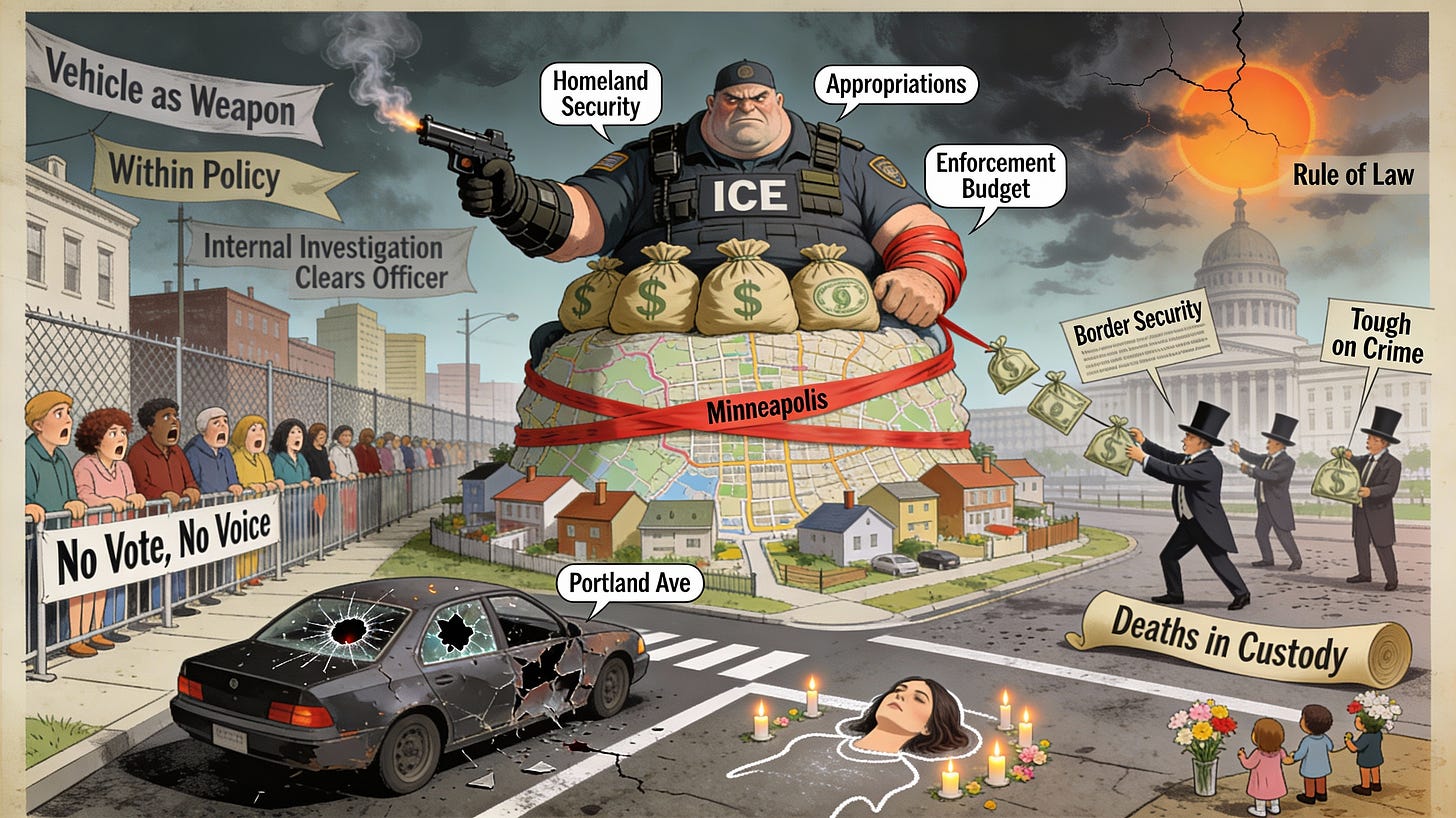

An armed federal officer shot a 37‑year‑old woman in the head on a quiet Minneapolis block and left her to die in a city that never voted for him, never hired him, and cannot fire him. The federal account is by now familiar: the woman, in her car, “used her vehicle as a weapon”; the ICE agent fired “defensive shots”; everything happened in an instant. The mayor’s account is just as blunt: having seen video of the incident, Jacob Frey called the killing “reckless,” rejected the self‑defense story as “bull——,” and told ICE to “get the [expletive] out of Minneapolis.”

It is tempting to process this as one more tragedy in a country saturated with them, to argue over angles and frames, to litigate whether the driver turned her wheel three degrees too far or hit the gas too fast. But the more important question is not whether one agent made the right call in a terrifying moment. It is how a system was built that keeps sending federal tactical teams into city streets with broad discretion, little local control, and every reason to err on the side of lethal force.

Building a Domestic Security Agency by “Accident”

ICE did not arrive as a brown‑shirted militia marching down Pennsylvania Avenue. It arrived as a line in a reorganization chart. After September 11, 2001, Washington fused immigration, customs, and various investigative units into a new homeland‑security bureaucracy, recasting migration from an administrative problem—paperwork, queues, visas—into an internal security threat. Over time, what had been a civil enforcement system governed by deadlines and docket pressures took on the posture of a police force: raids, long guns, tactical gear, joint task forces with local SWAT teams.

Budgets followed the fear. Immigration enforcement outlays climbed under both parties, framed as the price of “border security” and “rule of law,” even as the actual targets were increasingly long‑settled residents pulled from homes and workplaces far from any border. In political markets, the agency sells a simple product—numbers: arrests, detainers, removals. The game is to produce more units of enforcement at the margin, to justify next year’s appropriation. An officer who takes risks is an asset; an officer that admits to error is a liability.

That machinery does not have to be run by ideologues to behave like an internal security organ. It only has to be fed.

Above the City, Inside the City

Minneapolis did not invite the ICE operation that produced Wednesday’s killing. Local officials had no say in its timing, its tactics, or its rules of engagement. When things went predictably sideways—when an ICE officer fired at least twice into a car and hit a woman in the head—Mayor Frey’s first recourse was not to discipline anyone, but to hold a press conference and beg an agency he does not control to leave his city alone.

That is the core structural fact: federal immigration agents operate in a jurisdictional shadow. They work inside cities but outside local chains of command. A police chief who tolerates repeated abuses will face council hearings, budget threats, and electoral fallout. A federal immigration field office that racks up headlines can expect, at worst, a tense call from headquarters and some talking‑point revisions before the next oversight hearing in Washington. The people who bear the risks—immigrants, bystanders, neighbors—do not have a direct instrument to punish failure.

When an organization’s mistakes are paid for by outsiders with no vote in its internal affairs, the phrase “above the law” stops being rhetoric and starts describing a concrete incentive problem.

The Script: “Vehicle as Weapon”

The official narrative out of Minneapolis is almost a template. A DHS spokesperson says the woman “used her vehicle as a weapon,” tried to “run over our law enforcement officers,” and forced an ICE agent to fire “defensive shots.” In press briefings and on cable hits, the words are carefully calibrated: she is recast from a motorist into an “aggressive protester” or “rioter,” the car from an object into an enemy combatant.

This is not new. Federal agencies have learned, over the last decade of viral videos and lawsuit payouts, that justifying force is easier if the target can be folded into an existing category of public fear: the terrorist, the gang member, the rioter who turns a vehicle into a battering ram. Once the frame is set—”officer faced a vehicle attack”—the burden shifts. Any video that shows motion looks incriminating; any hesitation looks like a generosity the officer did not owe.

What matters in institutional terms is not whether this script is true in any given case. It is that the script exists, is rehearsed, and is deployed whenever an operation goes lethal. The more it is rewarded—by sympathetic coverage, by dropped charges, by internal findings of “within policy”—the more it will be used, and the more officers on the ground will come to see any ambiguous movement as license to fire.

When No One Local Can Say “Stop”

The public quarrel between Minneapolis officials and DHS over what actually happened is telling in its own right. Frey and Police Chief Brian O’Hara say they have seen video and that “there is nothing to indicate” the woman was the target of any investigation, and nothing in the footage that makes the federal self‑defense story credible. DHS and ICE, for their part, insist that the footage supports their account and have not rushed to release it in full.

In a healthy federal system, a city that believes a federal officer has killed its resident without justification would have tools stronger than adjectives. It could force disclosure of evidence, convene its own binding inquiry, even bar state or local cooperation with future operations until accountability is achieved. In practice, the levers here are mostly rhetorical and symbolic: protests at the scene, angry statements, maybe a resolution urging Congress to act.

The asymmetry is not an accident; it is how the enforcement system was designed. The agency that controls the guns controls the information, and the agency that controls the information controls the timeline on which the rest of the political system is allowed to react.

Budgets, Unions, and Manufactured Impunity

The institutional shield around ICE is reinforced by three overlapping forces: appropriations politics, organized labor, and fear.

First, the budget: immigration enforcement is one of the rare domains where both major parties have incentives to spend. One coalition demands toughness and numbers; the other, fearing backlash, tries to prove that it too believes in “orderly enforcement” and funds more “humane” cages, more investigative staff, more technology. There is no large, organized constituency for cutting ICE’s budget in half. There are many for keeping it intact or expanding it.

Second, the workforce: federal law‑enforcement unions and professional associations specialize in turning any high‑profile discipline effort into an attack on “front‑line heroes.” When misconduct cases arise—from detention‑center deaths to shootings in Walmart parking lots—they frame them as criminalizing split‑second decisions in dangerous conditions. That message plays well with appropriators, who do not want to be accused of undermining officer morale in an age of polarization and sporadic attacks on federal facilities.

Third, diffuse fear: Americans who are not targets of immigration enforcement are still told, constantly, that they live in a world of porous borders, fentanyl pipelines, and shadowy gangs. An agency that promises to stand between “us” and “them” can cash that ambient fear into both money and deference. Every scandal is an opportunity to remind the public that, whatever happened, the agents were confronting “dangerous people” in “volatile situations.”

Death as a Governance Signal

What the Minneapolis shooting clarifies is not the heart of one officer but the design of the system that put him there. A federal agent, incentivized to treat any deviation as threat, operating in a city where he does not answer to elected leadership, backed by an agency that knows Congress will not seriously cut its budget, faced a fast‑moving situation and chose the option that the institution has repeatedly rewarded: remove the perceived threat, justify later.

From the standpoint of political economy, the killing is not an outlier. It is a data point in a process. Investigations into prior ICE shootings, obtained through public‑records litigation, reveal at least 59 shootings by ICE officers in a six‑year span across 26 states and two territories, with at least 24 people injured and multiple deaths. Many involved cars; many ended with internal findings that cleared the officer or resulted in minimal sanction. In detention, deaths from medical neglect, suicide, and abuse spike, then fade from the news long before policy changes.

When outcomes like this recur under the same set of rules, the rules—not the bad apples—are what need explaining.

What a Different Immigration State Would Require

If the United States wanted an immigration enforcement system that did not look and feel like a domestic secret police to the communities it targets, it would have to do more than retrain officers or issue new talking points. It would have to change the structure.

That would mean, at minimum:

· Drawing a bright line between civil and criminal enforcement, with the armed, tactical deployments reserved for genuinely dangerous criminal suspects, not for serving civil papers on over‑stayed visas or rounding up day laborers.

· Giving cities genuine veto power over federal operations on residential streets, or at least meaningful conditions—advance notice, joint command, clear use‑of‑force rules—that cannot be unilaterally brushed aside.

· Making any death at the hands of immigration agents trigger an automatic, independent investigation with full public release of unedited video by default, and giving families access to civil remedies that bite into agency budgets rather than disappearing into general Treasury funds.

The point is not to leave borders unmanaged or to pretend that all enforcement can be gentle. It is to insist that, inside the country, state power obey the same constraints in immigrant neighborhoods as it does in affluent ones: necessity, proportionality, transparency, and a real chance to contest what has been done.

The Danger of Getting Used to This

Calling ICE an “American Gestapo” is not a historical statement; it is a warning label. The day‑to‑day reality is still far from a one‑party dictatorship with secret prisons and mass extermination. But the institutional logic—the creation of a well‑funded, politically insulated internal security agency that treats some human beings as expendable and some neighborhoods as expendable—points in a direction that history has seen before.

The Minneapolis killing is still under investigation. Full video has not been released. Details will matter for criminal liability and for the family’s pursuit of justice. But even if every contested fact broke in the officer’s favor—even if the car’s movements were more threatening than early reports suggest—the architecture that made this outcome likely would remain. As long as that architecture stays in place, the question is not whether another person will die under federal crosshairs in a city that did not invite them. It is when, where, and how much harder it will be, next time, to call the budget line what it has become.

An excellent piece. Thank you.