Fear, Paperwork, and the Price of Discrimination

The hidden economics of immigration enforcement—and what it would take to flip the incentives.

Governments routinely promise outcomes they lack the capacity to deliver. Immigration enforcement is an obvious case. You cannot directly police millions of people with tens of thousands of agents.

But limited capacity does not mean limited power. It means substitution.

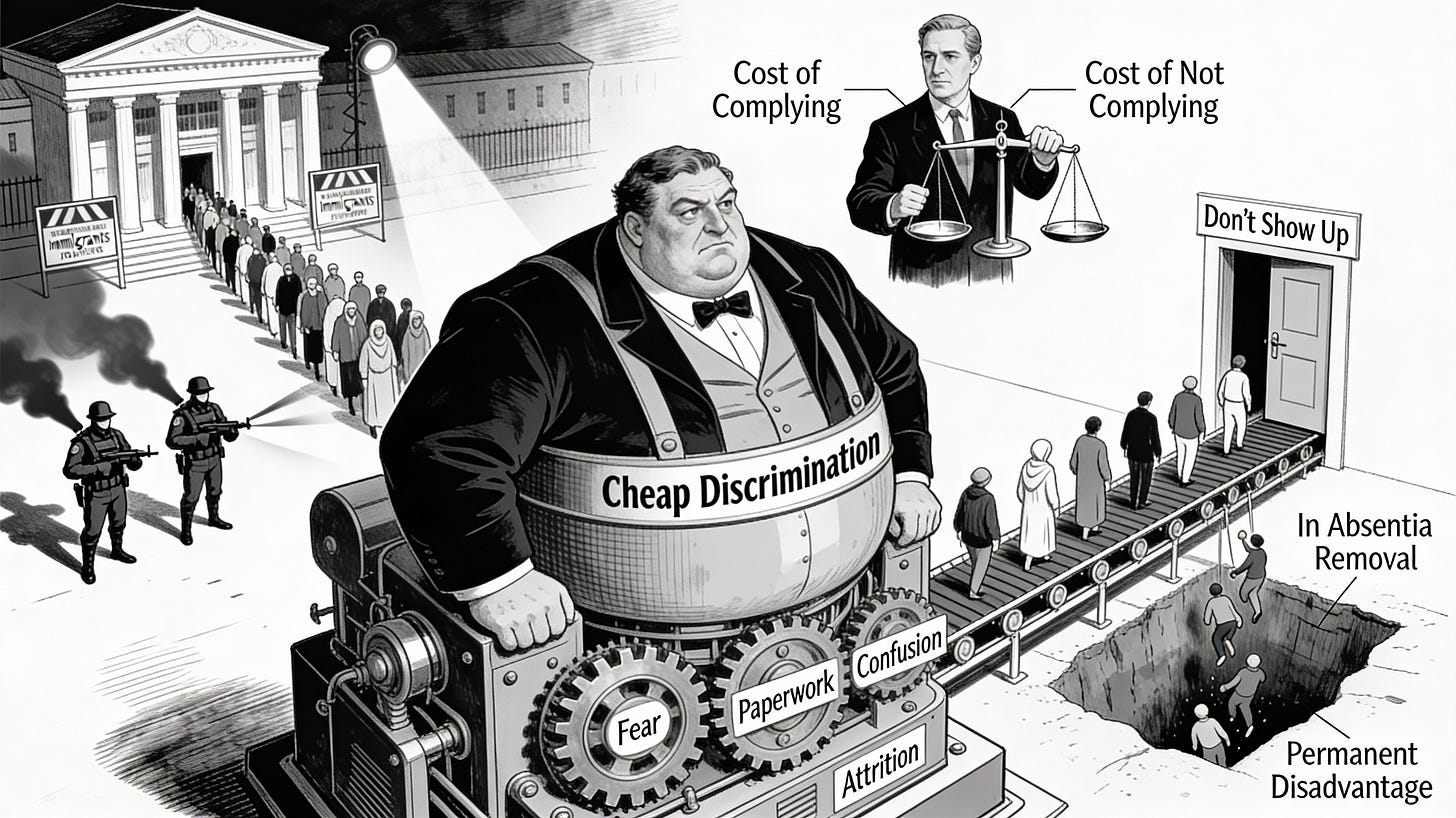

When direct enforcement is scarce, institutions rely on force multipliers—fear, paperwork, salience, and attrition. These tools don’t need to reach everyone. They only need to change expectations. And once expectations change, behavior follows.

That is the core logic of modern enforcement. It is less about catching people and more about pricing behavior.

A simple model

You don’t need a formal equation to see what’s going on. A stripped-down model works fine.

People compare two expected costs: the cost of complying and the cost of not complying. Each cost depends on how bad the outcome would be and how likely it is perceived to be.

Institutions do not need to change the law to change behavior. They only need to change how these costs are perceived.

Becker’s insight, without the jargon

Gary Becker’s core insight was simple: discrimination persists until it becomes too expensive. Markets do not eliminate discrimination because they are virtuous. They eliminate it because indulging discrimination has a price. If discrimination survives, it is because someone has found a way to avoid paying its full cost.

What has changed since Becker is not human nature. It is where the cost is hidden. Today, exclusion often lives inside procedures that appear neutral on paper but feel risky, confusing, or humiliating in practice.

Court attendance as a force multiplier

Immigration court makes this mechanism unusually clear. The state cannot deport everyone. But it does not need to. It only needs to make showing up feel riskier than disappearing.

When a respondent misses a hearing, the court can issue an in absentia removal order. No arrest. No search. No confrontation. Paper substitutes for physical enforcement.

A small number of visible enforcement events can update beliefs across entire communities, producing what researchers describe as chilling effects on court attendance, service use, and labor-market participation.

This enforcement logic mirrors the dynamics described in a recent piece I wrote.

How attrition replaces enforcement

Institutions facing capacity constraints often rely on the same sequence:

First, compliance is made emotionally expensive. Confusion, fear, or perceived exposure raise the psychic cost of following the rules.

Second, noncompliance is made to seem cheap—at least at first. Miss a step. Delay a response. Avoid a building. Nothing immediately happens.

Third, noncompliance is converted into durable disadvantage. Defaults, paperwork, and records lock in harm without proportional enforcement effort.

Finally, expectations do the work. Beliefs propagate socially. Behavior changes system-wide. At that point, the line between “caseload management” and discrimination stops being moral and becomes a matter of accounting: it is cheaper to exclude certain people than to design a system that takes them seriously

Where discrimination enters

Discrimination against immigrants—and against people perceived to be immigrants—often persists for the same reason: it is cheap institutionally, despite formal prohibitions on national-origin discrimination. Employers discriminate because exclusion feels safer than uncertainty. Landlords discriminate because blunt screening is easier than individual assessment. Agencies tolerate discrimination because attrition clears caseloads without confrontation.

This dynamic echoes the status-based exclusion described in Immigration and the New Color Bar

A note on first principles

I should be clear about my own view: I favor open borders. I think the presumption that peaceful movement requires moral justification is backward, and that most immigration restrictions fail any serious cost–benefit test.

But the argument here does not depend on accepting that position. It rests on a simpler claim: even restrictive systems do not operate the way their defenders describe.

Flipping the price

If discrimination survives because it is cheap, the durable solution is repricing.

Detection raises the probability exclusion is noticed. Escalating penalties make repetition expensive. Blocking substitution prevents neutral-looking proxies from laundering discrimination.

Together, these levers flip the expected-cost calculation Becker identified decades ago.

Why restrictionists should care about this

Even if you reject open borders, the incentive logic here still applies.

Restrictive immigration regimes do not eliminate migration. They reprice it in ways that systematically subsidize discrimination, informality, and coercion. In other words, we do not just tolerate discrimination; we subsidize it.

If a policy can only function by making compliance feel dangerous, that policy is already admitting its own administrative failure.

The broader lesson

Immigration enforcement makes the mechanism visible, but the logic is general. The same structure appears in credit markets, housing systems, welfare programs, and policing.

Discrimination is not inevitable. It survives because we subsidize it.

Appendix: What Restrictionist Economists Get Right—and What Their Models Leave Out

Yes, yes; I;m including an appendix. The main essay makes an institutional argument for open borders grounded in incentives, enforcement capacity, and cost-flipping. That argument is compatible with much of what serious restrictionist economists worry about—but it also exposes a structural gap in how those worries are usually modeled.

This appendix focuses primarily on George Borjas, because he represents the strongest labor-market case for restriction, and then briefly situates the argument alongside the work of Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, whose concerns are different and more institutional rather than distributive.

The goal here is not dismissal. It is clarification.

A. Borjas, taken on his own terms

Borjas’s core claim is not that immigration is harmful in the aggregate. It is that distribution matters, particularly in the short to medium run.

Stripped down, his argument is roughly this:

Immigration increases labor supply, especially at the low-skill end.

In competitive labor markets, this puts downward pressure on wages of similarly situated native workers.

Even if total output rises, some workers experience real losses.

Because distributional losses are politically and morally relevant, restriction is justified to protect vulnerable native labor.

This argument has real strengths that are often ignored by immigration advocates.

First, distributional effects are real. Aggregate gains do not eliminate localized losses, and pretending otherwise is analytically sloppy and politically self-defeating.

Second, adjustment is slow. Capital deepening, occupational mobility, and geographic relocation do not happen instantaneously. Borjas is right to reject frictionless textbook adjustment.

Third, political legitimacy matters. A policy that produces visible losers without compensation will face backlash regardless of its efficiency properties.

Nothing in the main essay requires denying any of this.

B. Where the Borjas framework quietly depends on restriction-induced distortions

The tension between Borjas’s conclusions and the argument in the main essay does not arise from wage arithmetic. It arises from what Borjas’s models treat as exogenous.

1. The strongest negative wage effects appear under partial restriction

Empirically, the largest wage pressures Borjas documents tend to appear in environments where:

workers lack full legal mobility,

labor markets are segmented by legal status,

employers face asymmetric enforcement risk,

and exit options are constrained.

In other words, illegality and legal precarity do much of the causal work.

From a public-choice perspective, this matters. Borjas often evaluates immigration in a world where restriction already exists—and then attributes observed labor-market outcomes to migration itself rather than to the institutional regime governing it.

That is not a moral critique. It is a modeling critique.

Restriction is not simply a reduction in labor supply. It is a restructuring of the labor market, one that systematically weakens worker bargaining power.

2. Restriction creates monopsony power

Legal precarity alters the outside options available to workers:

switching employers becomes risky,

credible exit threats disappear,

retaliation becomes cheaper,

compliance costs rise unevenly.

This gives employers monopsony power, which suppresses wages below marginal product. That effect harms immigrant workers directly and spills over onto native workers competing in the same labor markets.

Borjas’s framework typically assumes competitive or near-competitive labor markets. But restriction makes markets less competitive.

From the cost-flipping perspective, the conclusion is blunt:

If you care about low-skill wages, the worst equilibrium is partial restriction combined with large unauthorized populations.

This is not an ideological claim. It is a comparative-institutional one.

3. Enforcement is not a clean policy lever

Borjas often treats restriction as a binding constraint that operates through predictable channels. The main essay argues that this is not how restriction actually works.

In practice, enforcement is capacity-constrained and operates through:

selective enforcement,

fear-based deterrence,

paperwork traps,

discretionary policing,

and attrition rather than removal.

These mechanisms do not eliminate labor supply. They push it into informal channels. They distort bargaining relationships. They increase uncertainty. They impose costs unevenly.

Those distortions are not side effects. They are the operational core of the system.

Once those costs are priced in, restriction no longer looks like a neutral labor-market intervention. It looks like a subsidy to informality and discrimination.

C. The inversion: if Borjas is right, restriction may be the wrong tool

Once enforcement costs and institutional distortions are taken seriously, Borjas’s own concerns point toward a different policy ranking.

If immigration puts downward pressure on wages, making workers illegal amplifies that pressure by weakening bargaining power.

If the goal is to protect low-skill workers, restoring legal mobility and credible exit options dominates fear-based restriction.

If distributional harms matter, direct labor-market institutions—wage floors, bargaining rights, transfers—are cleaner tools than border coercion.

This does not claim that open borders eliminate all wage effects. It makes a narrower but stronger claim:

Enforcing restriction through fear, informality, and discrimination is a strictly worse way to address distributional concerns than allowing mobility and compensating losers directly.

That is an institutional dominance argument, not a utopian one.

D. Where Acemoglu and Robinson fit

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson are concerned less with wage effects and more with institutional stability. Their work emphasizes that economic outcomes depend on political and legal institutions, and that rapid changes in population or power can destabilize those institutions.

This concern is serious, and the main essay does not dismiss it. It reframes it.

Institutions are most fragile when large populations are governed through exclusion and informality. Shadow populations distort politics, weaken trust, and encourage discretionary rule. Fear-based governance erodes legitimacy.

Legality, by contrast, is stabilizing. Transparent rules with predictable enforcement reduce discretion, lower corruption, and make institutional constraints legible.

If institutions matter—as Acemoglu and Robinson argue—then policies that minimize discretionary coercion and maximize legal legibility should be preferred on institutional grounds alone.

Open borders do not guarantee institutional success. But restriction enforced through opacity and fear is itself an institutional stressor, not a safeguard.

E. The takeaway for restrictionists

You do not need to favor open borders to accept the core claim of this essay.

You only need to accept three premises:

Enforcement capacity is limited.

Incentives matter.

Discrimination survives when institutions make it cheap.

Once those premises are accepted, restrictionists face a hard question:

Why rely on border coercion to solve labor-market and fiscal problems that can be addressed more directly, more transparently, and at lower institutional cost?

That question does not dissolve disagreement. But it shifts the burden of proof.

And that, more than any moral appeal, is where serious policy debate should begin.

Excellent piece.