Replication Notes: Deportations, Wages, and the Hidden Incidence

Receipts, assumptions, and what would have to be true for "mass deportation helps workers" to be correct.

My latest piece on EconLog regarding the true costs of deportation is written to be readable without turning into a literature review. This post is the scaffolding underneath it: what I’m claiming, what I’m assuming, and what evidence would confirm—or falsify—the argument.

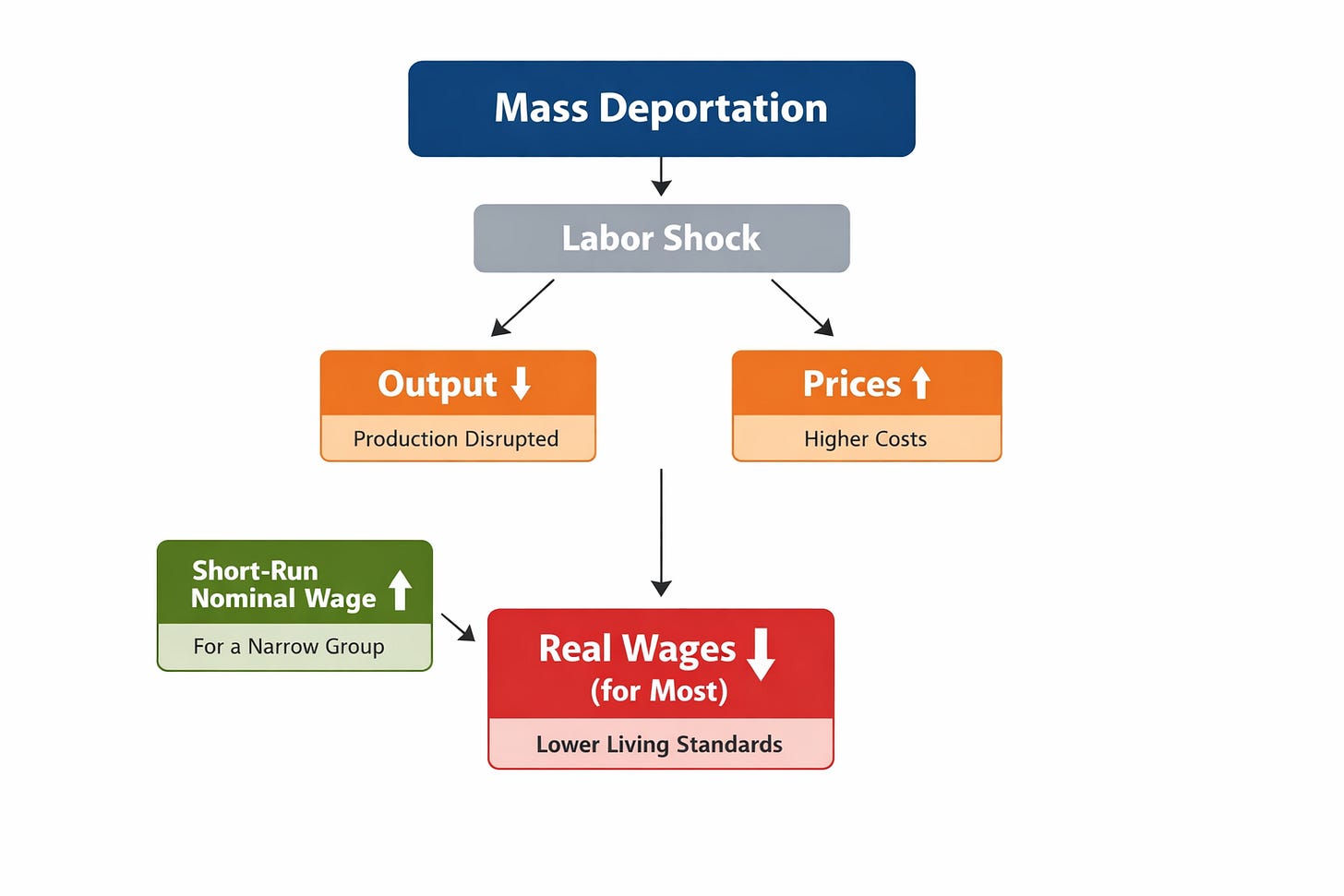

The thesis is straightforward. Removing 8–10 million mostly prime-age workers isn’t a clean “native wages rise” story. It’s a negative labor-supply shock that disrupts production, raises prices in bottleneck sectors, and reduces the productivity of complementary workers. If that’s right, the political promise (“workers win”) fails the real test: real wages and living standards for the majority.

This note does two things:

· Lays out the core claims (directional, mechanism-driven) and how you’d test them.

· Flags the seven most contestable empirical lines from the op-ed—the ones likeliest to draw fire—and states the confirm/deny patterns next to each.

1) What I’m actually claiming (not what people hear)

Most arguments in this space smuggle in a one-equation intuition: reduce labor supply → wages rise. That’s not false; it’s incomplete. In a real economy:

· labor is embedded in teams and task specialization

· sectors differ in how quickly labor can be substituted by capital or native workers

· firms adjust through output, hours, automation, relocation, and exit

· consumers pay through prices, not just paychecks

· complementary workers bear productivity losses when you remove key tasks from the production chain

So the claim isn’t “no one gains.” The claim is: any gains are narrow and temporary unless output holds and prices don’t rise—conditions that are empirically demanding.

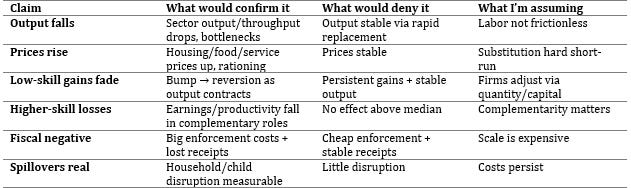

2) The core claims (with confirm/deny tests)

Core Claim A: Large-scale deportation reduces output materially

Why it matters: if output falls, you’ve shrunk the pie. Then “workers win” requires persistent wage gains large enough to offset less goods and higher prices.

· Would confirm: sector output/throughput declines in high-exposure industries; bottlenecks, delays, cancellations.

· Would deny: output holds steady via rapid replacement labor or productivity offsets.

· Assumption: replacement is not frictionless; organization and task networks matter.

Core Claim B: Prices rise where labor is hard to substitute (housing/food/services)

Why it matters: real wages depend on prices. Price increases are the hidden incidence.

· Would confirm: higher construction bids/timelines; food price pressure for labor-intensive crops; rationing/availability declines.

· Would deny: stable prices despite removal.

· Assumption: these sectors are labor-intensive and geographically sticky; automation is slow.

Core Claim C: Low-skill native wage gains—if they appear—are small and temporary

Why it matters: this is the main “pro-worker” mechanism advocates rely on.

· Would confirm: short-run wage bump followed by reversion as hours/output shrink or firms automate/exit.

· Would deny: persistent wage gains with stable/rising output and hours.

· Assumption: firms don’t bid wages up indefinitely; they adjust on non-wage margins.

Core Claim D: Higher-skill workers lose through complementarities

Why it matters: most of the labor force is not low-skill competing head-to-head; they’re complements upstream/downstream.

· Would confirm: reduced productivity/earnings for complementary roles in high-exposure markets; slower firm expansion.

· Would deny: no measurable effects above the median in exposed areas.

· Assumption: task specialization means missing “support” tasks reduce higher-skill productivity.

Core Claim E: Fiscal effects are negative once enforcement scale and lost tax base are included

Why it matters: the state is not doing this for free.

· Would confirm: large enforcement outlays plus revenue declines tied to income/payroll/consumption.

· Would deny: modest costs and stable receipts (implying fast replacement and stable output).

· Assumption: scaling enforcement to millions is administratively and legally expensive.

Core Claim F: Social spillovers impose real downstream costs

Why it matters: shocks to mixed-status households don’t stay private.

· Would confirm: sharp household income disruption; increased instability; measurable impacts on citizen children and local services.

· Would deny: minimal disruption (requiring quick replacement earnings and stable local economies).

· Assumption: transition costs persist and are nontrivial.

3) The 7 most contestable empirical lines (explicitly flagged)

These are the claims most likely to be attacked because they rely on indirect measurement, models, or causal inference. I’m not hiding that. I’m showing you what evidence would actually move them.

1) Labor-force magnitude: “8.5 to 10.8 million participate in the labor force.”

Why contestable: unauthorized populations and participation are inferred; estimates vary by method and year.

· Confirming pattern: multiple independent estimates converge on a multi-million working unauthorized population; sector exposure remains high across datasets.

· Denying pattern: credible estimates show the working unauthorized population is far smaller, and sector exposure collapses under cross-validation.

· Assumption: even with uncertainty, we are discussing a removal measured in millions, not a marginal enforcement change.

2) Macro contraction (models): “GDP would shrink by 2.6–6.8%.”

Why contestable: model outputs are assumption-dependent.

· Confirming pattern: different modeling approaches imply GDP losses of similar order under large-scale removals; local enforcement shocks show output declines in exposed areas.

· Denying pattern: plausible alternative models and empirical evidence show minimal GDP effects because replacement/substitution is fast.

· Assumption: the economy cannot offset removals quickly enough through capital deepening or substitution.

3) Construction exposure stack: “~19% unauthorized; 30%+ in some trades; ~1.5M workers; ~14% of the sector.”

Why contestable: a chain of precise figures is brittle.

· Confirming pattern: multiple sources show heavy concentration in key trades; enforcement shocks correlate with slower starts/completions, higher bids, longer timelines.

· Denying pattern: lower exposure across validated sources, and construction output/timelines remain stable after removals.

· Assumption: construction is bottlenecked by coordinated crews and trade-specific human capital.

4) Agriculture exposure + headcount: “nearly one-quarter… ~one-third… ~225,000 workers.”

Why contestable: agricultural labor categories differ across surveys; regional variation is large.

· Confirming pattern: consistent evidence of high unauthorized shares in harvest/sorting; disruptions show up as unharvested output, crop switching, higher costs.

· Denying pattern: unauthorized shares are small and farms replace labor quickly without output loss or cost pressure.

· Assumption: for many crops, labor is time-sensitive and substitution is slow.

5) Food price magnitude: “food price inflation approaching 9% (one model).”

Why contestable: single-model magnitudes invite “cherry-pick” critiques.

· Confirming pattern: multiple models predict meaningful food price increases; empirical disruptions in farm labor correlate with measurable category-level price pressure.

· Denying pattern: imports/substitution absorb the shock and prices barely move; any increases are transient.

· Assumption: pass-through is nontrivial in labor-intensive crops.

6) Secure Communities historical causal claim: “housing prices +5–10%… no lasting wage gains.”

Why contestable: causal inference fights; bundling housing and wages widens attack surface.

· Confirming pattern: quasi-experimental studies show enforcement intensification reduces construction activity and pushes housing costs upward; native wage gains (if any) fade.

· Denying pattern: robust studies show no effects on construction/housing, or durable wage gains without output contraction.

· Assumption: localized labor disruptions translate into supply constraints in housing-related production.

7) Wage magnitudes: “low-skill +1–3% short run; higher-skill −0.5 to −2.8% long run.”

Why contestable: wage elasticities vary; “skill” bins differ; ranges invite dueling models.

· Confirming pattern: small short-run gains in directly competing roles, offset by reduced hours/output; complementary occupations show productivity/earnings losses in exposed markets.

· Denying pattern: large persistent gains for low-skill natives with stable output and hours; higher-skill wages unaffected or rising in exposed markets.

· Assumption: firm adjustment caps wage gains and spreads losses through productivity and prices.

4) Claims table (compact)

5) Direction vs magnitude (what’s doing the real work)

Notice what’s doing the real work in the argument:

· Directional claims: large forced removals → output strain; bottlenecks → price pressure; complementarities → diffuse productivity losses; fiscal scaling costs money.

· Magnitude claims: exact headcounts, exact percentage ranges, specific historical effect sizes.

Even if a critic persuades you that a particular number should be 30% higher or lower, the incidence logic can still hold. To overturn the core conclusion (“most workers are worse off”), you’d need a stronger counter-pattern:

· Output holds.

· Prices don’t rise.

· Wage gains persist broadly.

· Complementarity doesn’t bite.

· Enforcement is cheap.

6) Annotated bibliography (minimal)

Coordination and knowledge (why coercive shocks have hidden incidence)

F.A. Hayek, “The Use of Knowledge in Society.”

The central lens: decentralized signals coordinate plans; large coercive interventions disrupt embedded knowledge in firms and communities.

Labor economics: substitution vs complementarity

Task specialization / complementarity literature (broad labor econ).

Key idea: some workers compete, many complement. The distribution of effects matters more than the slogan.

What matters empirically for this essay

Interior enforcement episode studies.

The test is not “did wages tick up somewhere?” but “did output hold and did real wages improve net of prices?”

Sector exposure work (construction/agriculture/services).

The key margins: throughput, delays, prices, and firm exit—not just wages.

Macro modeling exercises cited in the op-ed.

Use them as structured if-then machines: directionally informative, magnitude conditional.

7) What would change my mind (explicit falsifiers)

To overturn the core conclusion (“most workers are worse off”), you’d need to see the following pattern:

1. Removing millions of workers does not materially reduce sector output.

2. Prices in exposed sectors remain stable (housing/food/services).

3. Low-skill native wage gains are persistent, and not offset by reduced hours/employment.

4. Higher-skill wages/productivity are unchanged in exposed markets (weak complementarity).

5. Enforcement at scale is cheap, and tax receipts do not fall.

Treating deportation as a clean movement along a labor supply curve ignores how production actually works. Labor is embedded in teams, task networks, and local knowledge. Remove workers at this scale and you don’t just reallocate jobs—you degrade throughput, raise prices, and reduce productivity.

That’s why the incidence story matters: who wins is narrow; who pays is broad.

Next post

Next I will publish a one-page tool: The Immigration Enforcement Feedback Audit - a quick way to test whether a proposed intervention is preserving feedback or replacing it.

If you want to apply the framework to a specific proposal (housing, credit, labor markets, health care, energy), reply with the policy and what it is trying to stabilize, and I will map where the knowledge is being suppressed and where it will reappear.

Annotated Bibliography (Replication Notes)

Pew Research Center (Passel & Krogstad). “Methodology A: Unauthorized immigrant estimates” (Aug. 21, 2025).

· Use: Establishes how Pew constructs unauthorized estimates (residual methods + survey adjustments).

· Supports: The ‘these are estimates, not enumerations’ stance; justifies ranges and why precision is contestable.

· Limits: Indirect measurement; results depend on survey corrections and modeling choices.

Pew Research Center (Short Reads). “What we know about unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S.” (updated July 22, 2024).

· Use: Clean labor-force anchor (unauthorized immigrants in the workforce; share of workforce).

· Supports: ‘Multi‑million workforce footprint’ and why shocks won’t be marginal.

· Limits: Workforce measures are derived; definitions and years matter.

Penn Wharton Budget Model. “Mass Deportation of Unauthorized Immigrants: Fiscal and Economic Effects” (July 28, 2025).

· Use: Dynamic general‑equilibrium modeling of output and wage effects by skill/authorization under deportation paths.

· Supports: Output contraction and distributional wage effects (including potential long‑run wage pressure for higher‑skill workers).

· Limits: Conditional on elasticities and capital adjustment assumptions.

Peri, Giovanni & Sparber, Chad (NBER). “Task Specialization, Comparative Advantages, and the Effects of Immigration on Wages” (Working Paper 13389, Sept. 2007).

· Use: Canonical mechanism for task specialization and complementarity between immigrant and native labor.

· Supports: The complementarity channel behind ‘incidence beyond direct competitors.’

· Limits: Studies immigration inflows; applying it to deportation is a mechanism inference, not a one‑for‑one estimate.

Ottaviano, Gianmarco & Peri, Giovanni. “Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages” (JEEA published; NBER WP 12497 listed).

· Use: Broad empirical+structural reassessment of wage effects with heterogeneity by skill group.

· Supports: Wage effects are heterogeneous; average claims can miss distributional channels.

· Limits: Immigration ≠ deportation; use for mechanism and sign, not precise magnitudes.

USDA Economic Research Service. “Farm Labor” topic page (NAWS summaries; updated).

· Use: Institutional anchor on legal‑status composition of hired crop farmworkers and measurement constraints.

· Supports: Agriculture exposure and the ‘hard‑to‑substitute quickly’ sector channel.

· Limits: NAWS scope/definitions; regional and crop heterogeneity.

Baker Institute (Rice University). “Social and Economic Effects of Expanded Deportation Measures” (costing scenarios).

· Use: Cost estimates and capacity constraints for deportation at scale.

· Supports: Enforcement expansion is expensive and creates taxpayer incidence.

· Limits: Scenario costing depends on operational assumptions; critics may dispute inputs.

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). “Tax Payments by Undocumented Immigrants” (2024).

· Use: Standard reference for modeled federal/state/local tax contributions.

· Supports: Deportation reduces tax bases; payroll/consumption contributions are nontrivial.

· Limits: Modeled estimates; different methodologies yield different totals.

Pew Research Center. “U.S. Unauthorized Immigrant Population Reached a Record 14 Million in 2023” (Aug. 21, 2025).

· Use: Quantification of U.S.-born children living with an unauthorized parent (household context).

· Supports: Social spillovers are first‑order, not edge cases.

· Limits: Survey-based inference; household identification limits.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI). “As the U.S. Unauthorized Population Expands…” (mid‑2023).

· Use: Backup anchor on mixed‑status household and child counts under a different definition set.

· Supports: Reinforces spillover magnitude; helps triangulate ranges.

· Limits: Different definitions/timepoints; note differences explicitly to avoid ‘gotcha’ comparisons.