Argentina’s Libertarian Experiment: From Illusion to Entrenchment

How Trump’s bailout and a midterm victory converted Milei’s emergency program into a semi-permanent model—and what that says about libertarians willing to excuse it.

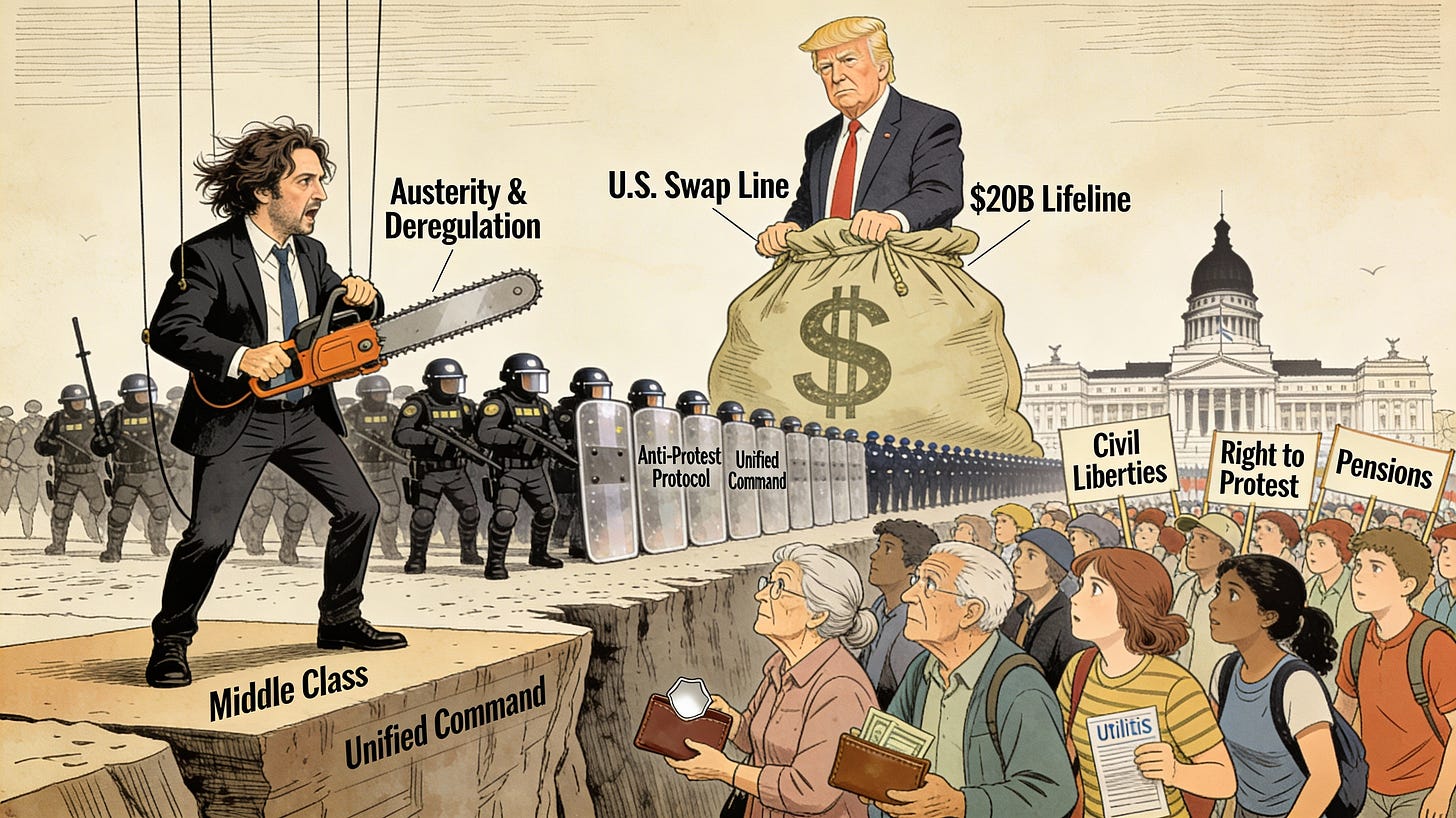

A little over a month ago, I argued that the “libertarian miracle” narrative around Javier Milei’s Argentina was premature at best and misleading at worst. The administration had delivered disinflation through shock austerity, but at a cost that included surging poverty, expanding police powers, and corruption scandals that made a mockery of Milei’s anti-caste rhetoric. More importantly, the project depended on a massive U.S. financial backstop from an ideologically aligned Trump administration—support that arrived just in time to stabilize the peso and tilt Argentina’s October 2025 midterm elections in Milei’s favor. My warning then was straightforward: external money and legislative validation would not fix the underlying problems; they would embolden Milei and normalize a governing model that pairs market reforms with civil-liberties restrictions and great-power patronage.

That prediction aged well. Milei’s party and its allies won decisively in the midterms, roughly doubling their representation in Congress and securing enough seats to sustain presidential vetoes and block impeachment. The electoral result was widely framed—by supporters and critics alike—as a referendum on austerity, deregulation, and Trump’s $20 billion swap line, which had been formalized days before the vote with explicit warnings from Trump that the money would vanish if Peronism won. Argentina repaid the swap in early January 2026—though quietly, using financing from an undisclosed multilateral lender—and the administration now points to that repayment as proof the whole episode was sound lending, not a bailout. Meanwhile, Argentina has exited recession, with GDP growth projected at 4–5% for 2025 and 3% for 2026, monthly inflation has dropped into the single digits, and the poverty rate has fallen from a peak above 52% to around 31–36% as real wages recover.

On paper, this looks like validation. Libertarian outlets now speak confidently of Milei “demonstrating the legitimacy of real-world libertarianism” and note that “things in Argentina got better, and the doomsayers went quiet.” Cato’s Free Society magazine ran a cover feature celebrating Milei’s 1,246 deregulations and framing the project as “Liberty Versus Power,” with the clear implication that liberty is winning. The problem is that the actual record tells a more ambiguous story—one in which macro stabilization has come alongside durable poverty, weakened institutions, and a security state that continues to expand, not contract. A follow-up is necessary because the midterm victory and Trump’s financial backing have not corrected these problems; they have entrenched them. What began as an emergency program justified by crisis has now been converted into a semi-permanent governing model, and the libertarians cheering it on owe a better account of what, exactly, they are willing to excuse.

The Macro Picture: Stabilization, Not Prosperity

Start with the numbers that defenders emphasize: inflation, growth, and poverty. Monthly inflation has indeed fallen dramatically, from peaks above 20% at the end of 2023 to below 2% by mid-2025, a disinflation path that even skeptics acknowledge is real. Argentina posted 3.3% year-on-year GDP growth in Q3 2025, ending six straight quarters of contraction, and forecasters now expect growth between 3–5% through 2026. The fiscal primary surplus is running above 1.6% of GDP, ahead of IMF targets. Poverty, which spiked to 52.9% in the first half of 2024 following Milei’s currency devaluation and subsidy cuts, has since declined to around 31.6% by official measures, with extreme poverty dropping from 18% to around 8%. Real wages in the private sector grew 10.4% between December 2023 and May 2025 as inflation eased faster than anticipated.

These are not invented numbers, and ignoring them would be dishonest. Milei’s program has delivered macro stabilization. The question is whether that stabilization constitutes success, and on what terms. The answer depends heavily on your baseline. If you compare mid-2025 Argentina to late-2023 Argentina—a country with triple-digit annual inflation, a collapsing currency, and fiscal chaos—then yes, things are measurably better on several dimensions. But if your standard is broad-based welfare improvement, the picture becomes far more ambiguous. Poverty has fallen from its 2024 peak, but it remains higher than when Milei took office, and well above historical norms; nearly a third of Argentines are still considered poor, and extreme poverty, though declining, affected millions more in 2024 than in 2023. The recent drop in poverty is driven largely by the mechanical effect of disinflation on official poverty measurements, which use a lag between income and consumption baskets; as UCA economists note, when monthly inflation falls, the one-month gap in the methodology flatters the numbers, and structural drivers—massive utility price hikes after subsidy elimination, for instance—remain underweighted in the official basket.

Growth is returning, but from an extraordinarily depressed base after a year-long recession induced by Milei’s own policies, and the recovery remains uneven across sectors and regions. Investment sentiment has improved, particularly after the removal of capital controls, but actual capital formation is still fragile, and the labor market showed a temporary pause in Q1 2025 that remains a “key point of attention” for forecasters. In other words, the economy is no longer in free fall, and some forward-looking indicators are positive, but calling this a “miracle” requires a selective memory about the pain endured to get here and a willingness to declare victory before broad prosperity has materialized. A fairer characterization is that Argentina has undergone a harsh stabilization, one that improved fiscal and inflation metrics at massive social cost, and is now experiencing a tentative, uneven recovery that may or may not prove durable. That is not nothing, but it is not the unambiguous success story libertarians are selling.

Trump’s Bailout and the Midterm Effect

The most significant political-economic event of 2025 was not any particular reform Milei enacted; it was the $20 billion currency swap line the Trump administration extended to Argentina in mid-October, days before the midterm elections. The deal was structured through the Exchange Stabilization Fund, an unusual mechanism that allowed the U.S. Treasury to backstop Argentina’s peso without Congressional approval, and it was accompanied by an additional $20 billion in private bank loans arranged with Washington’s implicit blessing. Trump made the political logic explicit: in a White House appearance with Milei, he warned Argentine voters that U.S. support would be withdrawn if Peronism won the midterms. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent described the package as a way to “utilize economic leverage to support a friendly administration” and assured that taxpayers would face no losses.

The timing and framing were unambiguous. The swap provided dollar liquidity at precisely the moment Argentina’s central bank needed to stabilize the peso and replenish reserves ahead of the vote. Analysts across the political spectrum acknowledged that the deal was designed to halt a market rout and shore up confidence in the weeks before Argentines decided whether to reward or punish Milei’s program. The electoral result—a decisive victory for La Libertad Avanza, with enough seats to sustain vetoes and block impeachment—was widely characterized as a referendum on austerity and on U.S. backing. Post-election, Milei’s economy minister thanked Bessent and Trump for their “prompt response” to attacks aimed at undermining the government during the campaign.

Argentina repaid the $2.5 billion it drew from the swap in early January 2026, two months after activation, and defenders have since pointed to that repayment as evidence the episode was prudent central-bank cooperation, not a political bailout. But the details complicate that narrative. The repayment was financed by an undisclosed multilateral lender—not the IMF, but another institution that has not been publicly named—meaning Argentina did not actually generate the dollars from its own reserves or export earnings; it borrowed from one creditor to repay another. The swap line remains active under the original terms, and Bessent has signaled ongoing support for Milei going forward. The whole arrangement looks less like a technical liquidity facility and more like a geopolitical credit line extended to keep a friendly government in power, with U.S. taxpayers and Argentine citizens bearing the tail risks if things go wrong.

From a classical liberal perspective, this presents a significant problem. Libertarians have historically been skeptical of great-power patronage, foreign aid conditioned on regime loyalty, and the use of public money to prop up allied governments. The IMF, World Bank, and U.S. bilateral lending programs have all been criticized—rightly—for creating moral hazard, subsidizing bad governance, and entangling the United States in foreign political disputes that serve narrow geopolitical interests rather than the rule of law or market discipline. Yet when the beneficiary is ideologically aligned, much of that skepticism evaporates. The Trump-Milei swap is difficult to distinguish in structure from the kinds of politically motivated bailouts libertarians used to oppose across Latin America, except that this time the recipient shares the right enemies and the right rhetoric. If the concern is that external financial lifelines reward failing governance and undermine accountability, then the concern should apply here. If the worry is that tying U.S. economic leverage to the electoral fortunes of foreign leaders violates principles of non-intervention and sound money, then the Trump administration’s explicit linkage of the swap to Milei’s midterm performance should be disqualifying. That those objections have largely gone unvoiced in libertarian circles suggests that the principles were more contingent than advertised.

The Police State That Libertarians Ignore

If the macro story is one of painful stabilization with uneven results, the civil-liberties story is simpler and grimmer: Milei’s government has systematically expanded state power over protest, dissent, and public space, and that expansion has continued and deepened since the midterms rather than been rolled back. The anti-protest protocol introduced by Security Minister Patricia Bullrich within days of Milei taking office remains in force. The protocol criminalizes roadblocks, requires prior notification for demonstrations, and authorizes the use of force—including identification, arrest, and criminal charges—against protesters who obstruct traffic. Human Rights Watch has documented that the protocol “in practice, criminalizes any disturbance to traffic arising from a demonstration” and grants police broad powers to disperse and detain.

The protocol was applied violently in June 2024, when police fired rubber bullets, tear gas, and punches at demonstrators protesting the Ley de Bases reform bill outside Congress, arresting 33 people, the last of whom was not released until September. In March 2025, security forces beat elderly retirees protesting pension cuts in what observers described as “the most ferocious” repression to date, using batons, rubber bullets, and tear gas in scenes that became a symbol of the government’s contempt for vulnerable populations. Such interventions are not isolated incidents; they occur “systematically every Wednesday” when retirees gather, according to civil society documentation.

Beyond the protocol, the government has institutionalized new mechanisms for securitizing economic activity. In September 2024, the Security Ministry created the Unified Command for Productive Security through Ministerial Resolution No. 893/2024, which coordinates federal, provincial, and local security forces to intervene against protests that affect “strategic” sectors: ports, mining sites, hydrocarbon fields, and energy infrastructure. The resolution frames social mobilization near economically important locations as a security threat requiring special policing, effectively turning labor disputes and environmental protests into matters of national economic defense. The command operates as a parallel security structure, bypassing normal judicial and administrative accountability, and its mandate has expanded as the government ties fiscal sustainability and IMF benchmarks to uninterrupted production in export-oriented sectors.

Human Rights Watch’s 2025 World Report on Argentina described the first year of Milei’s administration as marked by “new human rights challenges,” including “obstacles to people’s ability to exercise the freedom of peaceful assembly” and a March 2025 resolution broadening the scope for security officers’ use of firearms. That resolution allows lethal force “in an overly broad set of circumstances” and undermines both administrative and judicial accountability for police abuse, according to the report. The watchdog group also noted cuts to social program funding and “hostile official rhetoric against journalists and LGBT people” as part of a broader pattern of institutional deterioration. Other human rights organizations have documented that the proportion of protests met with state repression roughly doubled in 2025, with frequent use of force against vulnerable groups, including journalists covering demonstrations.

This is not the behavior of a government committed to shrinking the state or protecting individual liberty. It is the behavior of a government that treats social conflict as a policing problem, that views dissent as a threat to economic order, and that has built legal and institutional infrastructure to suppress both. The anti-protest protocol, the Unified Command, and the expanded use-of-force rules are not emergency measures that will sunset when inflation stabilizes; they are durable features of the governing model, and they were in place before the midterm elections gave Milei a stronger legislative hand. The logical inference is that more congressional allies and more external financial support will entrench these mechanisms, not unwind them. Libertarians who celebrate Milei’s deregulation of business while ignoring or minimizing his regulation of assembly, speech, and protest are engaged in a selective accounting that abandons the civil-liberties half of the classical liberal tradition.

Cato’s Defense and the Legitimacy Problem

The flagship libertarian defense of Milei has come from the Cato Institute, which has published multiple pieces arguing that the Argentine experiment vindicates real-world libertarianism and exposes the bad faith of its critics. In a March 2025 blog post, Cato’s Scott Lincicome wrote: “Then, a funny thing happened as Milei worked to enact his slash-and-burn agenda: Things in Argentina got better, and the doomsayers went quiet.” Lincicome argued that critics who predicted disaster have largely failed to issue “mea culpas” and that their silence amounts to an implicit concession that Milei succeeded. Cato’s Free Society magazine ran a fall 2025 cover story titled “Liberty Versus Power in Milei’s Argentina,” celebrating the administration’s 1,246 deregulations and framing the project as a battle against entrenched Peronist interests. The piece acknowledged that Milei’s “libertarian renewal is far from finished and under attack,” but treated the opposition as the primary threat to liberty, not the government’s own security apparatus.

This framing is revealing. Cato’s case for Milei rests on two moves: first, defining success narrowly in terms of inflation, fiscal balances, and deregulation, while treating civil liberties, poverty, and institutional quality as secondary or transitory concerns; second, attributing any criticism to ideological hostility or unwillingness to admit error, rather than engaging with the substance of the critique. The result is a defense that concedes less than it should and papers over tensions that cannot be papered over.

Start with the definition of success. Lincicome is correct that inflation has fallen and that some economic indicators have improved. But “things got better” elides the question: better for whom, and at what cost? Poverty spiked to 52.9% in early 2024 and remains above pre-Milei levels. Real consumption for lower-income households fell sharply before recovering partially. The pension cuts, subsidy eliminations, and public-sector layoffs that stabilized the budget imposed concentrated harm on the most vulnerable, and while some of that harm has since eased as inflation decelerated, the distributional cost of the adjustment was enormous. Declaring that “things got better” when a third of the country is still poor and elderly retirees are being beaten in the streets for protesting pension cuts is a moral and analytical failure. It privileges macro aggregates over lived experience and treats the pain of adjustment as either necessary or irrelevant, rather than as a cost that must be weighed against the gains.

More fundamentally, Cato’s celebration of deregulation ignores the other half of Milei’s program: the regulation of dissent. The same government that has rolled back business licensing requirements and labor protections has also criminalized roadblocks, broadened police use of force, and created a parallel security command to police “strategic” economic sectors. The same president who cuts taxes and shrinks ministries also centralizes power through decree, bypasses judicial accountability, and relies on foreign patronage to stabilize his political position. If libertarianism is a philosophy that prizes both economic and civil liberty, and that is skeptical of concentrated state power regardless of its stated aims, then Milei’s Argentina presents a test case that Cato is failing. The Free Society framing—“Liberty Versus Power”—suggests that Milei represents liberty and the opposition represents power, but the actual record shows a government that wields significant coercive power in service of some liberties (commercial) while suppressing others (assembly, protest, speech). That is not a libertarian project; it is a selective one, and the selectivity runs in the direction of economic elites and against the poor, the elderly, and those who organize in opposition to austerity.

The second move—dismissing critics as silent or discredited—is equally problematic. Lincicome claims that “doomsayers went quiet” and that critics owe apologies. But the criticisms leveled a year ago have largely been borne out. The warnings about poverty surges, institutional deterioration, and police-state tactics were accurate, not alarmist. The concern that Trump’s bailout would tilt the midterms and embolden Milei was vindicated. The prediction that external money would entrench rather than correct the model’s flaws has proven correct. If Cato’s position is that falling inflation outweighs all of this, then it should say so explicitly and defend that tradeoff on the merits. Instead, it treats dissenting voices as either bad-faith or embarrassed into silence, which is a way of avoiding the argument rather than winning it.

There is a version of the libertarian case for Milei that would be more honest: “Yes, he is expanding police power and relying on U.S. patronage, and yes, the social costs have been severe, but Argentina was on the brink of hyperinflation and state collapse, and all realistic alternatives were worse. In a second-best world, we accept an illiberal libertarian because the alternative is Peronism.” That argument has internal coherence, and it could be debated on consequentialist grounds. But it would require admitting that Milei’s project is not a clean vindication of libertarianism, that it involves significant authoritarian elements, and that celebrating it comes with moral and strategic costs. Cato has not made that argument. Instead, it has presented Milei as a straightforward success, dismissed or minimized the civil-liberties record, and framed critics as dishonest. That is not serious engagement; it is cheerleading.

What Has Been Normalized

The core problem with the libertarian defense of Milei is not that it overestimates the economic gains—reasonable people can debate the weight of disinflation versus distributional harm—but that it systematically ignores or excuses the political and institutional costs. Milei’s legislative victory in October 2025 did not occur in a vacuum. It came after a year in which the government systematically restricted protest, criminalized dissent, and used foreign financial backing to stabilize its political position ahead of the vote. The midterm result has since been treated as a mandate, and the administration now has the legislative strength to deepen both its economic reforms and its security measures. What has been normalized is a governing model in which market liberalization and civil-liberties restriction proceed in tandem, justified by the language of emergency and crisis, and underwritten by great-power patronage.

This is not the classical liberal vision of limited government, rule of law, and decentralized power. It is a model in which the state shrinks in some domains (social spending, business regulation) and expands in others (policing, surveillance, control of public space), with the net effect being a concentration of authority in the executive and a weakening of the institutional checks that protect vulnerable populations. It is a model that depends on external validation and financial support from Washington, which introduces a dependency and a geopolitical dimension that should trouble anyone worried about Argentine sovereignty and accountability. And it is a model that treats economic stabilization as a sufficient condition for success, even when that stabilization comes at the cost of enduring poverty, institutional degradation, and normalized repression.

Libertarians who endorse this model, or who minimize its costs, are making a choice. They are choosing to prioritize certain kinds of liberty—commercial freedom, fiscal discipline, deregulation—over others—freedom of assembly, freedom from arbitrary detention, freedom to organize and protest. They are choosing to excuse authoritarian tactics when deployed by a president who shares their economic agenda, even though they would condemn those same tactics if deployed by a Peronist or a leftist. They are choosing to celebrate a project that relies on foreign money and great-power backing, even though that reliance undermines the very principles of self-governance and market discipline they claim to uphold. Those choices have consequences. They weaken the intellectual coherence of libertarianism as a philosophy, they alienate potential allies who care about both economic and civil liberty, and they set a precedent that will be cited the next time a right-wing populist promises to cut taxes while expanding police power.

Conclusion: What Success Would Require

If this reading is wrong—if the optimists are correct and Milei’s Argentina is on a path to broad prosperity and institutional recovery—then certain things should happen in the next 12 to 24 months. The anti-protest protocol should be repealed or substantially narrowed, restoring the right to demonstrate without prior authorization or threat of criminal sanction. The Unified Command for Productive Security should be dissolved, and policing should return to normal administrative and judicial oversight. The government should stop using rubber bullets, tear gas, and mass arrests against retirees, students, and other vulnerable groups exercising their constitutional rights. Poverty should continue to fall not just from its crisis peak but below pre-Milei levels, and real wages and consumption should recover across income deciles, not just for the formal private sector. Investment should materialize in sustained capital formation, not just improved sentiment, and growth should prove durable rather than a brief rebound from a deep recession. The reliance on U.S. financial backing should end, with Argentina generating its own reserves and servicing its debts without recourse to geopolitical credit lines. And the administration should demonstrate that it can govern through normal legislative processes, not just by decree and veto, with genuine political competition and accountability.

If those things happen, then the skeptics—myself included—will owe a reassessment. A freer, more prosperous Argentina, governed by liberal institutions rather than emergency decrees and police protocols, would be a development to celebrate, not to resent. But that is not the trajectory we are seeing. The midterm victory has entrenched Milei’s power, not moderated it. The U.S. bailout has been repaid with borrowed money, not eliminated. The security apparatus has expanded, not contracted. And the libertarian establishment has largely chosen to look the other way, celebrating the deregulation while ignoring or minimizing the coercion.

That choice speaks volumes. It suggests that for many self-described libertarians, the anti-state rhetoric is more conditional than it appears—that the real priority is economic liberalization, and that civil liberties, due process, and restraints on police power are negotiable when the cause is politically aligned. It suggests that the principles of limited government and individual rights are more fragile than advertised, willing to bend when the alternative is a left-wing government or a continuation of the status quo. And it suggests that the classical liberal tradition, which historically prized both economic and civil liberty and treated them as inseparable, has fractured into competing factions, one of which is now willing to excuse a police state as long as it comes with tax cuts.

If libertarianism is to have a future as a coherent political philosophy rather than a rhetorical tool for partisan ends, it will need to reckon with what it has normalized in Argentina. It will need to ask whether celebrating Milei was worth the cost of abandoning civil-liberties principles, whether the short-term macro gains justify the long-term institutional damage, and whether a movement that excuses authoritarianism when it is ideologically convenient can credibly claim to stand for liberty at all. Those questions are uncomfortable, and they do not have easy answers. But they are the right questions, and they are long overdue.