Argentina’s Libertarian Illusion

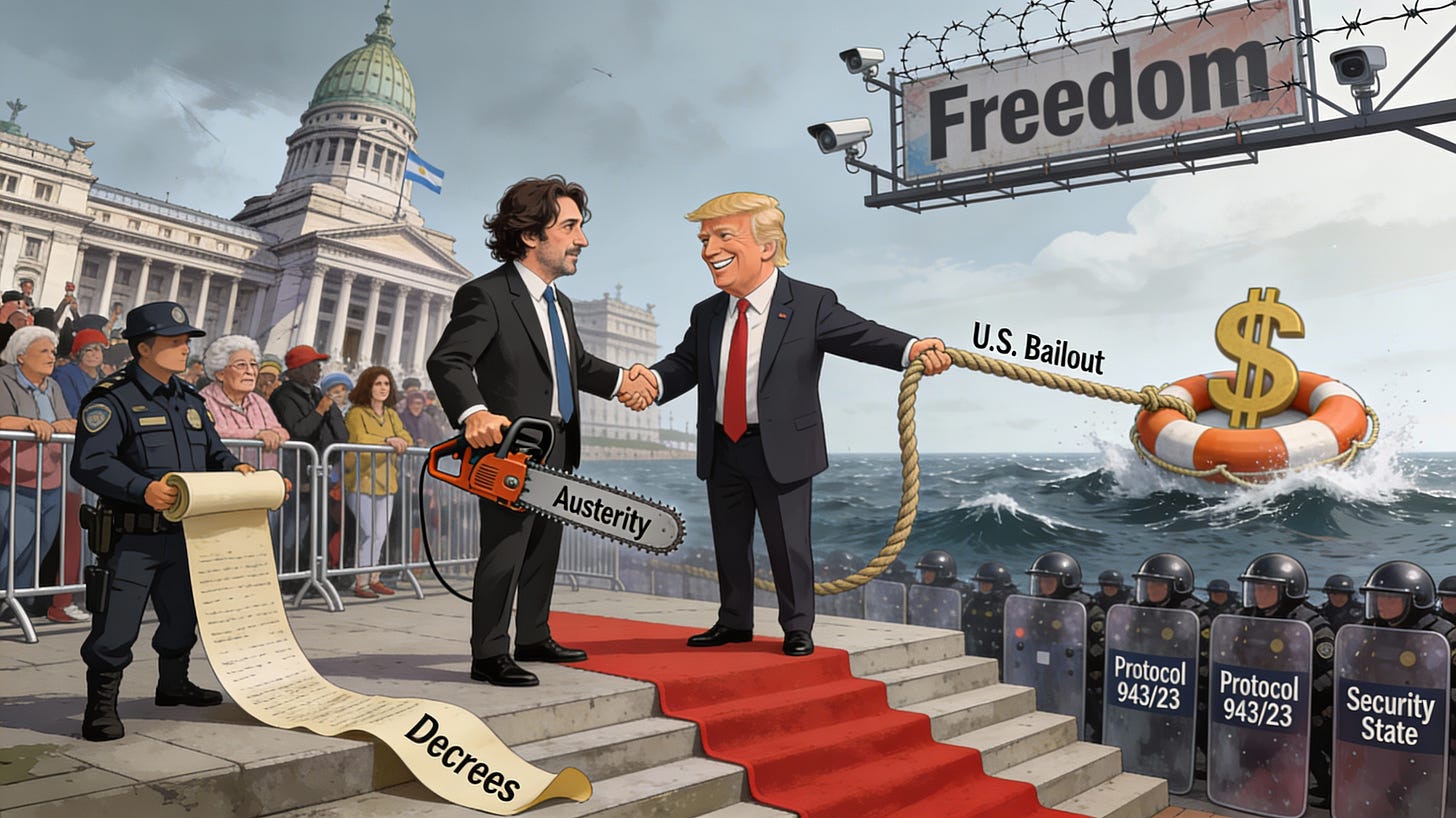

How Milei’s corruption, expanding security state, and Trump-fueled bailout victory risk discrediting markets and liberty along with his government.

A Skeptic’s Deeper Look

Javier Milei won office on a promise to smash “the caste,” his term for Argentina’s entrenched political and economic insiders. He paired that populist posture with radical libertarian rhetoric, advocating sweeping deregulation, fiscal shock therapy, and a downsized state that would, in theory, restore market-led growth. For many classical liberals and libertarians abroad, Milei represented a rare experiment: a democratically elected radical committed to shrinking government in a country where Peronism had long dominated.

I have long been skeptical of Milei—skeptical of the promises, skeptical of the movement around him, skeptical of the claim that “anarcho-capitalism” could be executed through state power. Yet fairness demands a deeper look at what he has actually done, not merely what he has claimed to do. What emerges from that closer examination is neither the libertarian miracle some admirers imagine nor the caricature his harshest opponents push. It is, rather, a record of corruption scandals, expanding police power, and mixed—often grim—economic results hidden behind fiscal headlines. Most troubling of all, it is a record that shows how electoral success and foreign backing can normalize and amplify these very pathologies.

What followed his inauguration, however, was less a clean break with the “caste” than a familiar pattern: concentrated power at the top, rushed rule by decree, and a growing gap between anti-corruption slogans and governing practice. The administration’s economic program did deliver some headline macro wins—most notably disinflation and a fiscal turnaround—but at the cost of a deep social shock and a narrowing of civic space.

Corruption: The “Anti-Caste” Meets the Disability Agency

For a government that promised to eradicate the “caste,” the corruption record looks depressingly familiar. At the center is the disability agency scandal, in which leaked audio and subsequent raids suggest a kickback scheme tied to contracts for medicines and services for people with disabilities, allegedly routing a three-percent commission to companies and intermediaries close to the presidency. Karina Milei—sister, confidante, and general secretary of the presidency—has been accused in media reports and opposition filings of benefiting from that arrangement, even as she has refused to appear before lawmakers and denies wrongdoing, while the administration shut down the agency itself and dismissed its director, a longtime presidential ally. At a moment of extreme austerity, when the same government was suspending disability benefits and warning that any increase in social spending would derail its fiscal plan, the image of insiders allegedly skimming from programs for the vulnerable undercuts Milei’s claim to moral superiority more effectively than any Peronist talking point ever could.

According to reporting by AP, The Guardian, and others, Diego Spagnuolo—Milei’s former personal lawyer, later head of the disability agency—was recorded describing a system whereby companies seeking contracts paid a cut that flowed through a network of middlemen, with a fixed share reportedly destined for the president’s sister. The amounts at issue, while modest by the standards of Argentina’s grand corruption, are politically explosive: bribes tied to programs meant for some of the most vulnerable citizens, in the midst of a brutal fiscal adjustment.

Financial markets reacted badly, with Argentine assets tumbling as the scandal intensified and investors questioned whether the administration’s anti-caste branding masked a standard-issue patronage machine. The government’s response—initial denials, the eventual dismissal of Spagnuolo, and a very public show of support for Karina at campaign rallies—did little to signal a clean internal reckoning. For a presidency that built its legitimacy on moral denunciations of past corruption, this is not a trivial reputational hit; it is a direct challenge to its core claim.

Nor is the disability-agency affair an isolated blemish. Analysts tracking the administration have flagged additional allegations around political fundraising, crypto schemes, and opaque relationships between officials and favored firms, suggesting a pattern in which insider access remains the coin of the realm even as the rhetoric rails against “caste” politics. The empirical picture is still evolving, but the trend line runs against the myth of a uniquely clean libertarian government.

A presidency that once defined itself against the “caste,” in other words, now looks uncomfortably entangled with the oldest form of caste politics: access and privilege behind the scenes. And as trust erodes, the temptation to substitute coercion for consent grows. That is where Milei’s security policy comes in.

Police Power Before the Vote: Building the Architecture of Repression

If the disability-agency scandal shows how easily libertarian rhetoric can coexist with old-fashioned graft, Milei’s security policy reveals something even more disquieting: how quickly a government elected in the name of freedom can move to oppressively police its own citizens.

While much of the world focused on Milei’s chainsaw rhetoric and fiscal arithmetic, his government was quietly building the legal and administrative scaffolding of a more muscular security state well before the latest congressional elections. Just days after taking office, the Ministry of Security issued Resolution 943/2023, the now-infamous “anti-picket” protocol that redefined road blockades and many street demonstrations as threats to public order, authorizing federal forces to disperse them without a court order.

The protocol does several things at once. It treats any protest that impedes vehicle traffic as a “flagrant offense,” empowering police to forcibly remove demonstrators, arrest them on the spot, and collect information on participants and organizations for potential criminal prosecution.²⁰ It also rolls back earlier rules requiring de-escalation and visible identification of officers, shifting the default from negotiation to rapid intervention. Human-rights groups from CIVICUS to local organizations such as CELS have documented how, in practice, Resolution 943/23 has served as a standing license to repress, enabling violent dispersal of marches and roadblocks throughout 2024.

The legal push did not stop there. In late December 2023, Milei sent Congress a bill to give the protocol statutory backing and to stiffen criminal penalties for protest organizers, defining any intentional gathering of three or more people that impedes transit or public services as a “demonstration” punishable by up to six years in prison. The draft would require prior notification of demonstrations, empower the Security Ministry to veto or alter protest plans, and force organizers to identify responsible individuals who could then face sanctions—a direct attempt to make collective action legally and personally costly. Wrapped into the same text was a sweeping declaration of “public emergency” until at least the end of 2025, extendable to cover the entire presidential term, effectively normalizing exceptional powers that blur the line between executive and legislature.

These were not abstract provisions. When pensioners rallied near Congress in March 2025 to protest meager benefits in the wake of the adjustment, Human Rights Watch documented indiscriminate use of force: tear gas canisters fired horizontally from riot guns, high-pressure water cannons turned on elderly demonstrators, and more than a hundred arrests, including older people who posed no threat. The Security Ministry justified the crackdown explicitly by invoking the anti-protest protocol; when a judge ordered detainees released, the government responded not by reconsidering the rules, but by filing complaints against the judge.

By the time Argentines went to the polls again, then, the architecture of repression was not a hypothetical future danger but an established fact: a protocol that criminalizes routine street politics, a draft law that seeks to codify and expand its reach, and a pattern of enforcement that treats social discontent as a policing problem rather than a democratic one. The elections did not create these tools; they ratified them, giving Milei a stronger mandate to wield powers he had already claimed.

Rule by Decree and the Anti-Protest Turn

If the corruption scandals expose Milei’s continuity with Argentina’s old political vices, his approach to security and civil liberties reveals a more novel, and arguably more troubling, turn. Very early in his term, Milei leaned heavily on emergency powers and decrees of necessity and urgency—“mega decrees” that bundle hundreds of policy changes—to advance a sweeping economic and regulatory agenda with minimal legislative deliberation.

At the same time, his government moved aggressively to harden the state’s response to social conflict. Security Minister Patricia Bullrich’s Resolution 943/2023 effectively criminalized traffic disruptions caused by demonstrations and granted federal security forces broad latitude to intervene. The protocol repealed the earlier “Nilda Garré” rules that had constrained police use of force at protests, required visible identification of officers, and emphasized de-escalation and dialogue before dispersal.

Human Rights Watch and a broad coalition of civil-society organizations have documented how the new rules allow security forces to use force even when demonstrators do not present a genuine danger, treating street blockades as a threat to “public order” per se. In practice, this has meant:

• Preemptive deployment of federal forces to break up roadblocks and marches challenging austerity measures.

• Expanded use of arrests and identity checks, including on public transportation, targeted at people suspected of joining protests.

• A chilling effect on unions, pensioners’ groups, and social movements that had long relied on disruptive protest as a political tool in Argentina’s contentious democracy.

This tough-on-protest stance did not emerge in a vacuum; it was rolled out precisely as Milei began implementing his most painful economic measures, with inflation spiking and real wages collapsing. In that sense, the security shift is not a separate policy domain but an integral part of his adjustment strategy: social peace enforced not by consensus, but by a security apparatus empowered to keep dissent from blocking “order” and “productivity.”

Economic Shock: The Chainsaw and the Ledger

But repression, however sophisticated its legal veneer, is ultimately a response to something deeper: the social shock produced by Milei’s economic program, which has turned the streets into both a barometer of pain and a target for control.

Milei’s program is often summarized as “chainsaw economics”: slash spending, deregulate aggressively, and allow market signals to restore growth. There is no question that the adjustment has been sharp. Within months, the administration devalued the peso steeply, scrapped or cut a wide array of subsidies, eliminated government ministries, froze public wages and pensions in real terms, slashed capital spending, and enforced primary fiscal surpluses after years of chronic deficits.

The immediate macro results have been striking. Annual inflation, which was running at over 200 percent when Milei took office, fell sharply over the course of 2024 and into 2025, with monthly inflation dropping from around 25 percent at the start of his term to low single digits by late 2024. The government also registered a primary budget surplus in early 2024 and maintained positive balances for much of the year, a rare outcome in recent Argentine history.

But the social and real-economy costs have been equally stark. As subsidies were removed and wages lagged prices, poverty surged to roughly 53 percent in the first half of 2024, up from about 40 percent the year prior—one of the fastest increases in decades. Consumption contracted steeply, and labor-intensive sectors were hit hard by both the currency shock and the collapse in domestic demand, pushing unemployment and underemployment higher.

Later data show some improvement as inflation receded. By late 2024 and into 2025, official statistics recorded declines in poverty rates and a modest recovery in consumer spending and industrial output, suggesting that the shock phase began to give way to a fragile stabilization. Yet even by the end of 2025, poverty remained elevated—over 30 percent—and extreme poverty still affected a significant share of the population, underscoring the depth of the earlier collapse.

Crucially, the adjustment has not eliminated structural vulnerabilities. Foreign reserves remain thin, external financing needs are large, and the sustainability of disinflation depends on maintaining fiscal discipline in a political system not known for restraint. Private investment, while showing some positive signals in sectors like energy and mining, has not boomed enough to promptly absorb displaced workers or to offset the contractionary effects of austerity elsewhere.

In short, Milei’s program has traded chronic high inflation and fiscal laxity for a harsh but more orthodox stabilization, with genuine achievements on the price and budget fronts but at an enormous distributional cost and under an increasingly authoritarian political umbrella. Whether that trade will yield durable growth or merely a different configuration of stagnation is, at best, uncertain.

Trump’s Bailout: A Political Endorsement with a Price Tag

It is against this backdrop of fragile stabilization and mounting social strain that Donald Trump’s bailout offer landed in Buenos Aires—not as a technocratic adjustment package, but as a political endorsement with a price tag.

As U.S. policy shifted under Trump’s return, Argentina became an ideological showcase—a test case for a libertarian-flavored shock program aligned with Washington’s new right-populist mood. The “bailout” on offer combined traditional tools—support at the IMF, enhanced credit lines, and backing for Argentine bonds—with more novel arrangements: guarantees for currency stabilization and a prospective investment facility tied to U.S. and allied firms. The details have been fluid and subject to negotiation, but the political message was not: continued U.S. backing would depend on Milei’s staying power and his ability to secure a stronger legislative mandate.

In the run-up to the recent National Congress elections, Trump made that implicit condition explicit. Public statements and diplomatic signals framed the support package as contingent on Argentina staying the course under Milei, warning that a fragmented or opposition-dominated Congress would jeopardize Washington’s willingness to underwrite Argentina’s stabilization. For a country exhausted by inflation and wary of yet another lost decade, the prospect of external support—however politically freighted—mattered.

The combination of disinflation, even if fragile, and the promise of U.S. backing helped Milei’s coalition outperform expectations, shoring up his position in Congress. The same president who had begun his term as an outsider with a weak legislative base emerged from the elections with strengthened parliamentary leverage and renewed international cover for his agenda.

Legislative Victory as License for Coercion

The danger is not merely that foreign policy has become a lever in Argentina’s domestic politics, but that electoral success driven in part by an external bailout will embolden Milei to double down on the strategies already on display: harsh adjustment from above, backed by an expanding security apparatus.

With a more favorable Congress and explicit U.S. endorsement, the incentives tilt toward deepening reliance on decree powers and fast-track legislation to push further deregulation and privatizations, reducing space for negotiated compromise. The government has also proceeded to institutionalize a Unified Command for Productive Security (Resolution 893/2024), coordinating security forces to protect sectors deemed economically “strategic” and authorizing intervention against protests that affect ports, mining sites, and energy infrastructure. Even as legal challenges mount and over a thousand organizations have petitioned for repeal of the anti-protest protocol, the government has continued to defend and operationalize it, signaling no willingness to backtrack.

The dynamic is straightforward and troubling: electoral and legislative success grants greater political cover for repressive tools that were first deployed under the pretext of emergency. Once normalized, those tools are unlikely to remain confined to left-wing roadblocks or union marches; they become part of the standard repertoire of state power, available to any future administration.

For a movement that sells itself as pro-freedom, a presidency that relies increasingly on protocols, decrees, and security coordination to manage dissent sits uneasily with classical liberal principles of limited, rule-bound government. The long-run risk is that “order” and “investment climate” become the standing justification for interventions that shrink not only the state’s economic footprint, but also citizens’ space to contest policy.

How the Bailout Emboldens Milei—and Risks Deepening Failure

External support can buy time, but it can also buy impunity; when money and legitimacy arrive with few questions asked, governments have less reason to reconsider the habits that brought them to the brink.

A bailout that stabilizes reserves and buys time can, in principle, give a government room to soften the harshest edges of austerity, reconnect with democratic institutions, and build a broader coalition for reform. In this case, the early signs point in the opposite direction: political capital is being spent on entrenching executive dominance and security-driven social control, not on liberalizing civic space or dispersing power.

The expansion of security powers becomes more consequential in light of Milei’s legislative successes. With a stronger mandate in Congress, the government has proceeded to institutionalize coercive tools that would otherwise face greater resistance. The risk for classical liberals is obvious. If Milei continues to conflate “freedom” with deregulation and budget cuts while tolerating or enabling corruption and coercive policing, the ideological brand suffers. When the experiment fails—and the structural and political constraints make failure a live possibility—the blame will not fall only on an idiosyncratic Argentine leader, but on free-market ideas more broadly.

An Unpopular Reading, and a Hope

Among many classical liberals and libertarians, criticism of Milei is still seen as giving ammunition to the wrong side—handing talking points to Peronists, socialists, or advocates of permanent macro-populism. The temptation is to treat any market-oriented government facing a hostile establishment as beyond reproach, or at least beyond serious scrutiny until the experiment runs its full course.

This essay rejects that temptation. The record so far shows a government that has delivered genuine progress on inflation and fiscal discipline while incubating serious corruption scandals, shrinking civic space, and building a security apparatus increasingly integrated with its economic strategy. Trump’s bailout offer and the resulting legislative victories have not moderated these tendencies; they have empowered them.

This will not be a popular stance in circles eager for a libertarian success story in a major Latin American economy. But analysis is not a popularity contest. If classical liberalism means anything, it must mean a consistent concern for the rule of law, limited government, and civil liberty, not just a preference for lower inflation and fewer ministries. For Argentina’s sake, the hope must be that this reading will age poorly—that the corruption probes will lead to genuine house-cleaning, that the anti-protest protocols will be rolled back, that economic stabilization will broaden into inclusive growth without permanent authoritarian drift.

If posterity proves this skepticism wrong, that outcome would be welcome. A freer, more prosperous Argentina, governed by liberal institutions rather than by emergency decrees and police protocols, would be a cause for celebration, not embarrassment. I would be happy to be proven wrong. But I cannot, in good conscience, pretend that the evidence so far points in that direction.