When Presidents Control Money: Why the Trump–Powell Clash Threatens the Dollar and Global Markets

Central banks were made independent for a reason. Once criminal law becomes a tool to dictate interest rates, the U.S. stops having monetary policy in any meaningful sense.

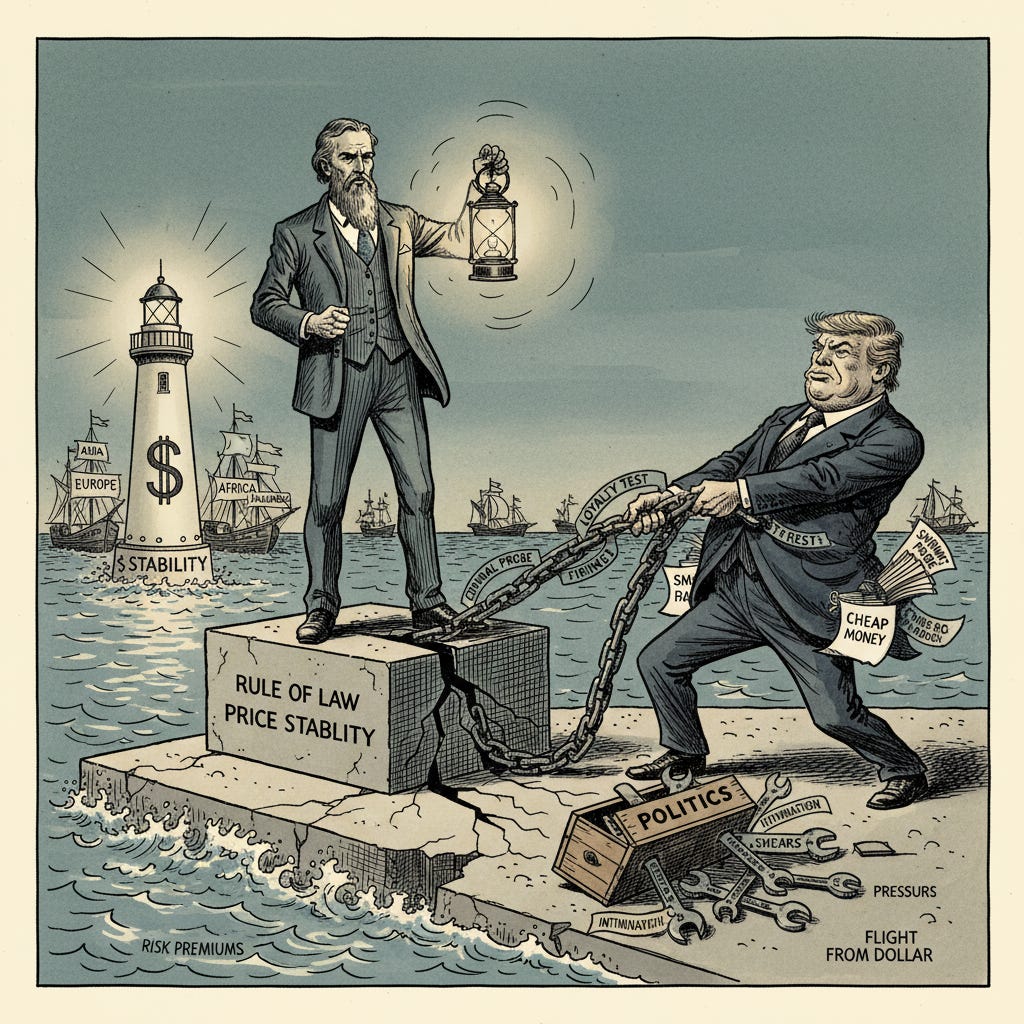

Central banks exist to say “no” when elected officials most want them to say “yes.” When a president turns that refusal into grounds for legal retribution, the line between an independent monetary authority and a political instrument begins to blur—and with it, the foundations of both domestic stability and the dollar‑based global order.

When politics captures money

For as long as there has been money, there has been the temptation to manipulate it. In democracies, that temptation takes a modern form: the pressure on central banks to keep interest rates too low for too long, financing deficits cheaply and juicing short‑term growth at the expense of long‑term stability.

Modern central banking is meant to stand in the way of that temptation. Congress gives the Federal Reserve a mandate focused on price stability and maximum employment, then insulates its leadership with staggered, fixed terms and legal protection from removal on purely political grounds. The goal is not to make central bankers unaccountable philosopher‑kings, but to make it difficult for any one president to bend monetary policy to an electoral calendar or a personal agenda.

This arrangement is a response to hard experience. Economies that let governments treat the printing press as a branch of the treasury tend to live with chronic inflation, volatile cycles, and a credibility tax in the form of higher borrowing costs. The more politics captures money, the more the currency itself becomes a kind of campaign promise—plausible in the moment, but easily broken when circumstances change.

The Powell problem

That background is what makes the current confrontation with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell so dangerous. Trump did not enter office with a neutral posture toward the Fed; he has treated interest rates as one more lever to be pulled in the service of growth targets, stock‑market performance, and the fiscal strain of his own agenda.

During his earlier term, Trump publicly berated Powell for not cutting rates as aggressively as he wanted and mused in interviews about whether he had the power to demote or remove the Fed chair. Those threats were troubling enough, but they stopped short of using the machinery of law enforcement. Today’s conflict has crossed that Rubicon.

In January 2026, Powell confirmed that he is under federal criminal investigation and linked that probe directly to the Fed’s refusal to yield to presidential pressure on interest rates and policy decisions, including spending on the central bank’s own facilities. When a sitting president uses the prospect of prosecution against a central bank chair whose offense consists of executing statutory duties at arm’s length from the White House, independence is no longer an abstract institutional concern. It becomes personal.

From criticism to coercion

Democratic accountability does not require presidents to remain silent about central banking. Criticism of monetary policy is not a constitutional violation; it is often a healthy part of public debate. Elected officials will always, and rightly, argue about the appropriate balance between inflation and employment, between vigilance and growth.

But there is a meaningful difference between criticism and coercion. Criticism is a speech act; coercion is the threatened use of state power to force a change in behavior. When a president signals that careers can be ended, reputations destroyed, or criminal charges pursued if the central bank fails to deliver the “right” interest‑rate path, that is not oversight. It is a message to current and future policymakers that technocratic judgment will be punished if it conflicts with political convenience.

The law recognizes this distinction. Statutory protections for the Fed chair’s term and removal reflect a judgment that monetary policy should not turn on whether the incumbent president prefers lower rates for re‑election or higher rates to “discipline” some disfavored sector. Once criminal investigation is added to the toolkit, monetary policy ceases to be a rules‑based, institutionally bounded process and begins to look like another domain where loyalty is enforced through fear.

Time inconsistency, revisited

Economists have a dry phrase for the problem central bank independence tries to solve: time inconsistency. In the short run, a burst of surprise inflation can lower real wages, stimulate output, and help governments finance debt more easily. In the long run, the private sector adjusts, wages catch up, and all that remains is higher inflation and less trust.

If the same actor who benefits most from that short‑run boost—the government—also controls the printing press, promises of restraint become cheap talk. Markets and households, anticipating the temptation to inflate away problems, will demand compensation: higher nominal interest rates, inflation hedges, and shorter maturities. The system internalizes a permanent inflationary bias.

Independent central banks are, in effect, a way of tying the government’s hands. By delegating day‑to‑day control over monetary instruments to officials with secure tenure and a narrow mandate, society tries to make credible a promise that would otherwise be unbelievable: that it will not always take the easy way out. When presidents can credibly threaten to remove or prosecute those officials, the knot starts to loosen.

The dollar as world infrastructure

The consequences of that loosening do not stop at America’s borders. The dollar is not merely the unit in which U.S. wages are paid and domestic debt is denominated. It is the dominant reserve currency, the standard unit for invoicing global trade, and the anchor for trillions of dollars in cross‑border contracts.

Foreign central banks hold dollar‑denominated assets, especially U.S. Treasuries, not out of sentiment but because the dollar has been reasonably stable and the institutions behind it have been seen as reasonably insulated from short‑term political whim. Multinational firms borrow, lend, and book profits in dollars for similar reasons: it reduces uncertainty and transaction costs to operate around a currency whose guardians are constrained by law rather than by loyalty.

This stability is a kind of public good. When the Fed responds to inflationary shocks with predictable, rule‑like behavior, it provides a focal point for expectations around the world. Countries that peg to the dollar, or that manage their own currencies with an eye on U.S. policy, can plan around that behavior. Investors can structure portfolios confident that the dollar will not suddenly become a tool for financing one administration’s ambitions at the expense of everyone else.

Politicization and global spillovers

If that confidence erodes, the costs show up quickly. Suppose global investors come to believe that the president can, in practice, dictate interest rates or punish central bankers for resisting. In that world, buying a 10‑year Treasury is no longer a bet on the long‑run behavior of a semi‑independent institution. It is a bet on the desires and staying power of particular political actors.

Rational investors will respond by demanding a higher risk premium on dollar assets, shortening the maturity of the debt they are willing to hold, or diversifying into other currencies. None of these responses is catastrophic on its own; the dollar is deeply entrenched, and there is no obvious successor currency waiting in the wings. But over time, a slow bleed of trust can fragment the system. Instead of one widely trusted monetary anchor, the world drifts toward a patchwork of partially trusted alternatives.

That fragmentation matters in crises. When financial shocks hit, the Fed’s ability to act as a global lender of last resort—backstopping dollar funding markets and stabilizing cross‑border flows—rests on the assumption that its emergency actions are guided by technocratic judgment within a legal mandate, not by partisan favor or presidential whim. Politicizing monetary policy weakens that assumption, making every intervention suspect and every backstop more contested.

The illusion of cheap money

Proponents of tighter presidential control over the Fed rarely present their case as one for inflation or instability. More often, the argument is that elected officials should have the power to insist on lower rates to support growth, ease debt service, or correct what they see as the central bank’s overly cautious bias. In this telling, independence is a kind of unaccountable technocratic veto on prosperity.

But this is a mirage. If markets begin to doubt the Fed’s willingness to resist political demands for cheap money, the long‑term cost of borrowing will rise, not fall. Creditors care less about today’s policy rate than about the expected path of inflation over the life of their loans. The more they worry that the president can order the central bank to accommodate fiscal excess or electoral promises, the more they will insist on inflation compensation up front.

The irony is stark: the attempt to force low rates through political pressure can end up producing persistently higher rates through the back door of lost credibility. What looks like a shortcut around technocratic caution turns into a toll road, with the bill paid by future taxpayers and borrowers who had no say in the bargain.

For Fed‑skeptics, a hard lesson

Many critics of the Federal Reserve come from a different direction. They see central banking itself as the source of instability, resent its role in crisis interventions, or question the legitimacy of a small committee steering the price of credit for an entire economy. For them, arguing in favor of central bank independence can feel like defending a flawed institution against democratic control.

Yet the alternative on offer is not a currency board, a gold standard, or a competitive private‑money regime. It is personal rule over money, exercised by presidents and their lieutenants through threats, removals, and now, criminal investigations. Whatever one thinks of discretionary monetary policy, replacing constrained technocratic judgment with unconstrained political will is a step toward greater arbitrariness, not less.

This is the hard lesson for Fed‑skeptics: institutional design is comparative. A world in which the Fed’s mandate is narrowed, its rule‑based behavior strengthened, and its emergency powers more tightly defined may be attractive. A world in which presidents can effectively dictate the stance of policy under threat of prosecution is not. Independence is not about trusting central bankers absolutely; it is about refusing to trust anyone absolutely with the power to reshape money in real time.

Law, norms, and the point of no return

Central bank independence rests on more than statutes. It depends on norms: shared expectations about what political actors will not do, even when the law might plausibly permit it. Past presidents have criticized Fed chairs, leaked displeasure, or quietly lobbied for policy changes. What they generally did not do was suggest that refusal to comply could itself become grounds for legal jeopardy.

Once that norm is broken, it is difficult to restore. Future presidents—of either party—will inherit a precedent in which deploying prosecutors or regulatory scrutiny against central bankers is no longer unthinkable, merely unusual. Each use makes the next one easier. Over time, a posture of deference to the Fed’s institutional role gives way to a default assumption that monetary policy is simply another front in the permanent campaign.

Legal independence without normative restraint is fragile. A statute that protects a Fed chair’s term does little good if the chair must constantly weigh whether an unpopular decision will trigger retaliatory investigations, public smears, or demands for resignation. At some point, the choice is between formally codifying a subordinate role for the central bank or admitting that the independence on paper has become a polite fiction.

What is at stake now

The confrontation with Powell should be read in that light. It is not merely a disagreement over the proper level of interest rates or the timing of balance‑sheet adjustments. It is a test of whether the United States will permit the fusion of monetary power and prosecutorial leverage in the hands of a single elected official.

If that fusion takes hold, the costs will show up first in small ways: an extra fraction of a percentage point on bond yields, a little more hesitation from foreign reserve managers, a little less confidence among firms signing long‑term contracts in dollars. Over time, those small frictions accumulate into a less forgiving environment for growth, investment, and crisis management. The U.S. will discover that undermining the Fed in pursuit of flexibility has made the entire system more brittle.

Central bank independence was never about trusting experts for their own sake. It was, and remains, about constraining the most dangerous uses of political power—the subtle ones, where the costs are pushed into the future and spread across the entire economy. In turning that constraint into a target, today’s assault on the Fed risks trading a flawed but functional monetary order for something both more personal and more fragile. The dollar, and the global system it underwrites, may not break tomorrow. But they can be bent out of shape in ways that are very hard to fix.