Visa Pauses Are the New Wall

How America cuts legal immigration in the shadows—and why the macro costs show up later

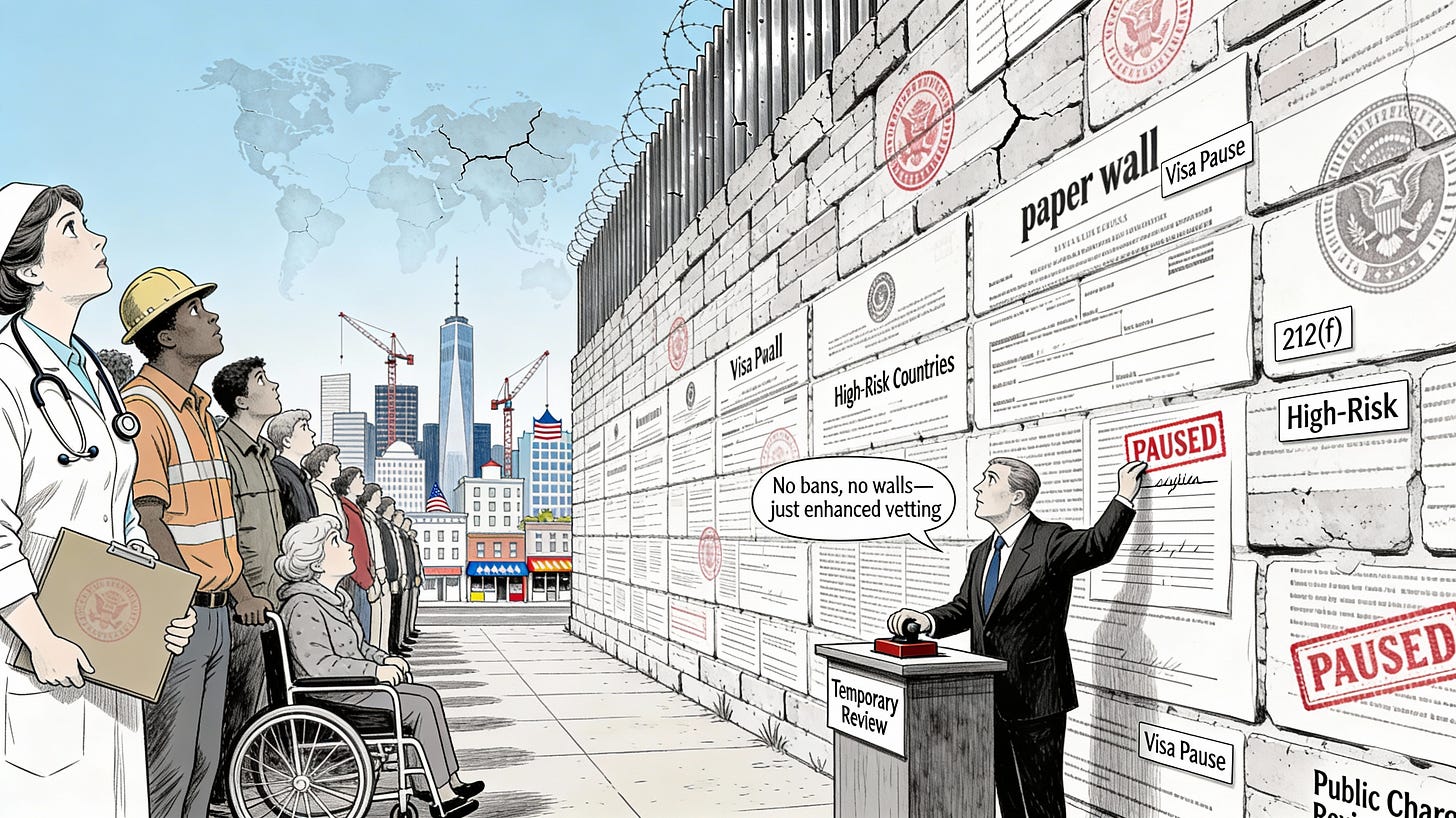

When immigration politics heats up, the camera always finds the same things: fences, raids, protests, and angry speeches. Those images shape the argument because they feel like the policy.

But the most effective restriction often isn’t the kind you can film. It’s administrative—quiet changes in how visas are issued, how long cases sit, what counts as “risk,” and which applicants are routed into delay. That’s the logic of the paper wall.

According to an immigration advisory summarizing State Department guidance, immigrant visa issuances are expected to be paused for nationals of 75 countries deemed “at risk” of becoming a public charge beginning January 21, 2026. The headlines are about walls and raids. The real action is in the consular back office.

From concrete wall to paper wall

If you wanted to cut immigration sharply, you could try to build a massive physical barrier and dare Congress to stop you. Or you could do something much smarter, politically: announce a “temporary” pause in immigrant visas, wrap it in technocratic language about public benefits, and let the backlog quietly grow.

One advisory (Alston & Bird) says the State Department will “pause all immigrant visa issuances for nationals of a large group of countries identified as being at elevated risk of using public benefits,” effective January 21, 2026. Nonimmigrant visas—tourist, work, and student—are explicitly untouched. Applicants can still show up for interviews at U.S. consulates. But unless they hold a passport from a country not on the list, they will not leave those interviews with an immigrant visa.

In other words: the door is not slammed shut, but the lock has been quietly changed.

Who is actually blocked?

The administration’s own framing emphasizes that this is not a Muslim ban, not a travel ban, not even a “ban” at all—just a pause for “enhanced vetting” of would‑be immigrants’ likelihood of becoming a public charge. But when you look at the list, the pattern is hard to miss.

Nationals of 75 countries would not be able to receive immigrant visas from consulates abroad while the pause is in force. The list includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, Haiti, Nigeria, Russia, Syria, and Yemen, among many others, with a strong tilt toward poorer countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Family‑based migrants are especially exposed, because a large share of those green cards are processed abroad rather than as adjustments of status inside the United States.

Crucially, the policy:

· Applies to immigrant visas processed at U.S. consulates overseas, not to petitions filed with USCIS inside the United States.

· Leaves nonimmigrant visas (B‑1/B‑2 tourists, H‑1B and L‑1 workers, F‑1 students) formally untouched, even as “enhanced public charge vetting” expands to all applicants.

· Has no fixed end date; it is tied to a broad “policy review” that can last as long as the administration wants it to.

The exception is telling: dual nationals from these countries can escape the pause if they apply under a passport from a country not on the list. If risk were purely individual, a second passport shouldn’t change the assessment. It makes more sense if the goal is to reduce flows from particular places while maintaining plausible deniability.

The “public charge” story vs. the numbers game

Formally, this is about public benefits. The State Department and administration lawyers lean heavily on the idea that the government must ensure immigrants are “financially self‑sufficient and do not become public charges” before granting green cards. No politician ever lost a campaign by promising to keep welfare rolls smaller.

But if the concern were really about the standard public charge test, policy could be changed in two much more direct ways: tighten financial sponsorship requirements across the board, or rewrite the public charge rule to count more forms of assistance. Instead, the administration chose a tool that cuts overall numbers on a nationality‑by‑nationality basis while calling it a pause for “review.”

This is where public choice economics helps. Opaque tools like section 212(f) travel and visa restrictions are politically attractive because:

· The benefits are concentrated on vocal restrictionist constituencies who notice every new limit.

· The costs fall on diffuse future workers, consumers, and U.S. citizens who would have sponsored relatives—a group that is unorganized and not yet here to vote.

· A conspicuous wall invites protest, litigation, and endless coverage. A consular “pause” gets an explainer or two, then fades into the background as “just how the system works now.”

The macro hit: shrinking the future on the quiet

Immigration isn’t just a moral question; it’s also the main input into America’s labor‑force math.

A recent update from Wendy Edelberg, Stan Veuger, and Tara Watson at Brookings estimates that net migration in 2025 was between –295,000 and –10,000 (depending on the series)—potentially the first time in at least half a century the U.S. saw negative net migration. They project that net migration in 2026 will probably remain at very low or negative levels.

That matters because nearly all growth in the working‑age labor force in recent years has come from immigration. U.S.‑born working‑age population growth is weak; the 2022–24 surge was what made robust job creation compatible with a stable unemployment rate. In their updated calculations, Brookings estimates that:

· Sustainable monthly job growth (“breakeven employment growth”) fell to roughly 20,000–50,000 jobs by late 2025, and could turn negative in 2026 if restrictive policies persist.

· Reduced immigration will shave tens of billions of dollars off consumer spending over 2025–26 and modestly dampen GDP growth.

The visa pause is not the only driver of those numbers, but it directly contributes by cutting one of the most straightforward channels of legal inflows: green cards issued abroad. Brookings notes that State Department monthly data show immigrant visas issued abroad fell meaningfully in 2025 relative to 2024; under plausible assumptions they estimate a drop from roughly 670,000 in 2024 to about 560,000–575,000 in 2025.

From the perspective of an employer or a renter, that translates into something concrete:

· Fewer nurses, home health aides, and caregivers in a rapidly aging society.

· Fewer construction workers and tradespeople when housing supply is already tight.

· Fewer entrepreneurs starting restaurants, daycares, logistics firms, and repair shops in neighborhoods that need investment.

A wall is dramatic and visible. A green‑card slowdown shows up later as “labor shortages,” “skills gaps,” and mysteriously weaker growth.

Visa pauses as the new wall

The Trump years have repeatedly shown that the most powerful tools in immigration policy are not the ones you can see from a drone. The pattern, from the first term to the second, has been to discover and refine a repertoire of quiet instruments: travel bans, slow‑walked refugee admissions, narrower asylum standards, work‑permit bottlenecks, and now a mass pause on immigrant visa issuances for “high‑risk” nationalities.

Visa pauses are the new wall in three ways:

· Durable: once a consular system is re‑oriented toward suspicion and delay for certain nationalities, it can take years—and explicit political will—to unwind.

· Invisible: there are no dramatic images of people turned away at airports, just families quietly canceling plans when their number in the queue no longer moves.

· Deniable: every individual case can be explained away as the byproduct of necessary “enhanced vetting,” rather than the predictable result of a broad numerical cut.

To be clear, visa issuance can fall for multiple reasons; the point is that a pause is a deliberately scalable lever. And for anyone who cares about fiscal prudence, labor‑market health, and the rule of law, this is the worst of both worlds: the U.S. gets the growth drag of reduced immigration and the moral cost of slamming the door on people who played by the rules—without even the minimal virtue of democratic clarity about what’s being done.

If the country wants fewer immigrants, that choice should be made openly: with clear numerical targets, transparent cost–benefit analysis, and explicit legislative votes. Instead, the emerging model is to let “temporary” pauses, travel bans, and backlogs do the work—shrinking America’s future behind a smiling bureaucratic face.

The wall made for a great chant. The paper wall may prove far more effective—and far harder to tear down.