Trump’s Fed Chameleon

Kevin Warsh’s shape‑shifting on interest rates and QE is bad news for anyone who wants a predictable, nonpartisan central bank anchored in classical liberal principles.

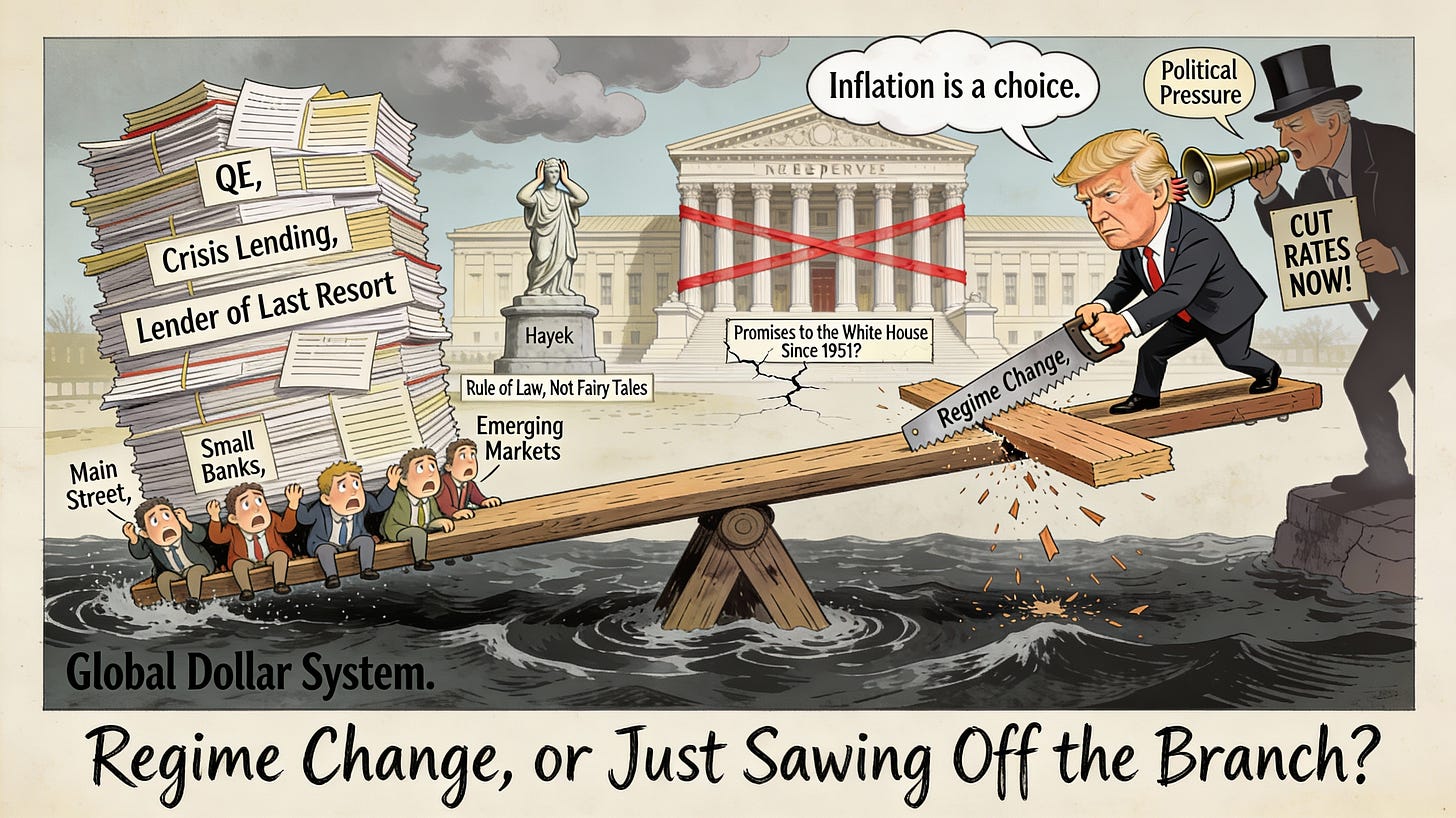

Kevin Warsh’s nomination to chair the Federal Reserve arrives wrapped in the rhetoric of “regime change”—a promise to remake monetary policy after what he views as years of institutional drift and overreach. For classical liberals skeptical of concentrated discretionary power, that language should be appealing. After all, the case for rules over discretion in monetary policy has deep roots in our tradition, from Hayek’s warnings about the knowledge problem to Friedman’s advocacy for predictable, mechanical frameworks that constrain the arbitrary exercise of authority.

But Warsh’s actual track record and stated priorities reveal something more troubling than a principled commitment to rules-based policy. What we’re likely to get instead is a Fed chair whose ideological commitments—particularly his hostility to the central bank’s balance sheet and his proximity to political power—threaten to hollow out the Fed’s capacity to respond to crises while simultaneously making monetary policy more vulnerable to short-term political pressure. That’s not a recipe for rule of law in monetary affairs. It’s a recipe for institutional decay masked as reform.

The Illusion of Rules

Classical liberals have long understood that central bank independence serves a crucial constitutional function: it insulates monetary policy from the time-inconsistency problem that plagues democratically accountable institutions. Politicians face strong incentives to juice the economy before elections, inflate away debts, and defer hard choices to successors. An independent central bank operating under a clear mandate and predictable framework theoretically constrains those incentives, much the way constitutional limits on taxation and spending constrain fiscal profligacy.

Warsh positions himself as a champion of this tradition. He criticizes the Fed for “mission creep” and argues for narrowing the central bank’s focus back to core functions. That sounds disciplined. But look more carefully at what he actually advocates, and the picture becomes murkier. During his 2006–2011 tenure on the Board of Governors, Warsh consistently leaned hawkish—favoring tighter policy even in 2010, when unemployment remained near 10 percent and output was still recovering from the financial crisis.

That might reflect a principled commitment to price stability over short-run employment concerns. But Warsh never dissented from FOMC decisions during his entire tenure, voting with the majority every single time. According to transcripts, he told colleagues at the November 2010 meeting that he would only support QE2 “out of respect for Chairman Bernanke,” and that if he were in the chair, he would not lead the Committee in that direction. He worried aloud about removing “the burden from those that could actually help reach these objectives” and placing it on the Fed.

This reveals the central tension: Warsh claims to want rules, but his actual behavior suggests something closer to discretion guided by a particular macroeconomic worldview—one that systematically downplays the employment side of the dual mandate and expresses deep skepticism about unconventional tools even in extraordinary circumstances. That’s not the same as supporting a nominal GDP targeting rule or a Taylor Rule that automatically adjusts to economic conditions. It’s just a different flavor of discretion, one that happens to err on the side of doing less rather than more.

The Balance Sheet Obsession

Warsh’s signature issue is his relentless criticism of the Fed’s expanded balance sheet, which grew from under $1 trillion before the financial crisis to over $8 trillion during the pandemic. He argues that large-scale asset purchases have gone “too far,” artificially suppressing long-term interest rates, encouraging excessive risk-taking on Wall Street, and creating “monetary dominance” in which markets become dependent on central bank support.

There’s a kernel of legitimate concern here. The Fed’s balance sheet has grown dramatically, and there are reasonable debates about whether QE’s benefits justified its risks, whether reinvestment policies have been too passive, and whether the central bank should commit to a smaller long-run footprint. But Warsh’s position goes well beyond nuanced critique. He literally resigned from the Fed in 2011 over continued asset purchases, and has spent the years since calling for hard limits on balance sheet size and a new “Treasury-Fed agreement” to formalize those constraints.

From a classical liberal perspective, this should set off alarm bells. The case for rules-based monetary policy isn’t about shrinking the central bank’s toolkit in the name of ideological purity—it’s about establishing predictable, credible frameworks that allow the central bank to respond systematically to changing economic conditions. Hayek’s concern was that discretionary authorities lacked the knowledge to fine-tune the economy; his solution was competitive currencies and stable monetary frameworks, not hobbling the lender of last resort in the middle of a financial panic.

What Warsh proposes is closer to the latter. By treating the balance sheet as inherently dangerous above some arbitrary threshold, he risks turning crisis response into a political negotiation rather than a technical exercise. When the next liquidity crisis hits—and it will—does the Fed chair have to go hat-in-hand to Treasury, asking permission to expand the balance sheet because he’s bound by some new interagency compact? Does he have to worry about whether asset purchases will breach a ceiling enshrined in political agreements rather than economic need?

That’s not a rule. It’s a straitjacket. And it places the burden of macroeconomic stabilization back onto fiscal policy—precisely the domain where public choice problems are most acute, where rent-seeking dominates, and where short-term political incentives systematically trump long-run stability. If you take Warsh at his word that he dislikes balance sheet expansion, it means more falls onto Congress and Treasury. Given what we know about how those institutions operate, that should terrify anyone who cares about sound money and limited government.

The Public Choice Problem

Which brings us to the most troubling aspect of Warsh’s nomination: the political context in which it’s happening. President Trump has made no secret of his desire for lower interest rates, going so far as to publicly attack Jerome Powell and float the idea of firing him. Trump wants “crisis-level” rates near 1 percent, and he wants a Fed chair who will deliver them. Warsh was selected precisely because he is ideologically and personally aligned with the administration, with deep GOP ties and a long record of political engagement.

Classical liberals should recognize this pattern. Public choice theory teaches us that institutions don’t operate in a vacuum—they respond to the incentives created by their political environment. An “independent” central bank whose chair owes his position to a president demanding easy money, and who shares that president’s broader ideological project, is not truly independent in any meaningful sense. The formal legal structure of independence remains, but the informal norms and practical constraints that make independence credible have eroded.

Warsh may believe he can navigate this tension—that he can deliver some version of Trump’s desired rate cuts while maintaining the Fed’s institutional legitimacy. But that’s exactly the kind of time-inconsistency problem that rules are supposed to solve. Once you’ve opened the door to political considerations shaping monetary policy, it’s very hard to close it again. Markets will price in the expectation that the Fed’s decisions reflect not just economic data but also the political needs of whoever appointed the chair. That raises risk premia, undermines the credibility of forward guidance, and makes stabilization policy harder in the long run.

The irony is that Warsh’s stated agenda of “regime change” could actually accelerate this dynamic. By positioning himself as an outsider determined to remake the Fed, he invites precisely the kind of political scrutiny and pressure that erodes institutional norms. He gives cover to future administrations—of either party—who want to treat the Fed as just another policy lever, subject to the same short-term political calculus as tax rates or spending programs.

The Supervisory Void

There’s one more dimension worth noting: Warsh’s vision of a narrower Fed would likely mean pulling back on bank supervision and financial stability research, particularly on topics like climate risk, algorithmic bias in lending, and other areas he views as beyond the central bank’s core mission. From a limited-government perspective, that might sound appealing—why should unelected technocrats be making policy on environmental issues or social justice?

But this misunderstands what effective supervision requires. Modern financial systems are complex and interconnected. Risks emerge from unexpected places—interest rate risk at Silicon Valley Bank, operational risk at crypto-exposed institutions, concentration risk in commercial real estate. A central bank that lacks the research capacity and institutional flexibility to monitor emerging threats is a central bank that will be blindsided by the next crisis.

This isn’t about mission creep. It’s about maintaining the information infrastructure necessary to do the core job of financial stability. Warsh’s critique treats any Fed activity beyond narrow interest rate setting as suspect, but that betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of how crises actually unfold. They don’t announce themselves with flashing lights saying “macroeconomic shock incoming.” They emerge from the complex interaction of regulations, market structures, technological change, and institutional behavior. You need eyes and ears throughout the system to spot them early.

Curtailing that capacity in the name of ideological purity is penny-wise and pound-foolish. It saves a bit of political capital now—avoiding accusations that the Fed is straying into climate activism or social policy—but it increases the likelihood of a severe crisis down the road when the Fed is caught flat-footed because it deliberately chose not to look at something important.

The Constitutional Case for Monetary Flexibility

Classical liberals sometimes fall into the trap of thinking that “rules” means “rigid” and “limited” means “small.” But the case for constitutional constraints on government power isn’t about minimizing government per se—it’s about channeling power through predictable, accountable processes that prevent arbitrary exercises of authority. A well-designed monetary rule doesn’t eliminate central bank discretion; it structures that discretion around clear objectives and transparent decision-making.

The Fed we need isn’t one with a crippled balance sheet and a chair afraid to use unconventional tools. It’s one that operates under a clear mandate—say, a nominal GDP level target—with the full toolkit available to hit that target, and with transparent communication about how decisions map to the rule. That framework allows the central bank to respond aggressively in crises without creating the expectation of permanent intervention. It anchors expectations while preserving flexibility.

Warsh’s vision offers neither. It combines balance sheet dogma with political proximity, hawkish instincts with no-dissent collegiality, and “regime change” rhetoric with a track record of conformity. That’s a recipe for a Fed that does too little in the next crisis, justifies inaction with appeals to institutional limits, and ultimately loses credibility precisely because it fails to stabilize the macroeconomy when stabilization is most needed.

Classical liberals should want a Fed that is powerful enough to prevent depressions but constrained enough to avoid inflationary excess (I know such a statement is anathema to many libertarians, but reality is what reality is). That requires both a credible rule and the institutional capacity to implement it. Warsh offers the appearance of restraint without the substance of rule-based policy, and the appearance of reform without the reality of institutional strengthening. That’s the worst of both worlds—and we shouldn’t be fooled by the packaging.