Tribute for an Island

Trump’s tariff blackmail over Greenland turns the liberal trade order into a protection racket

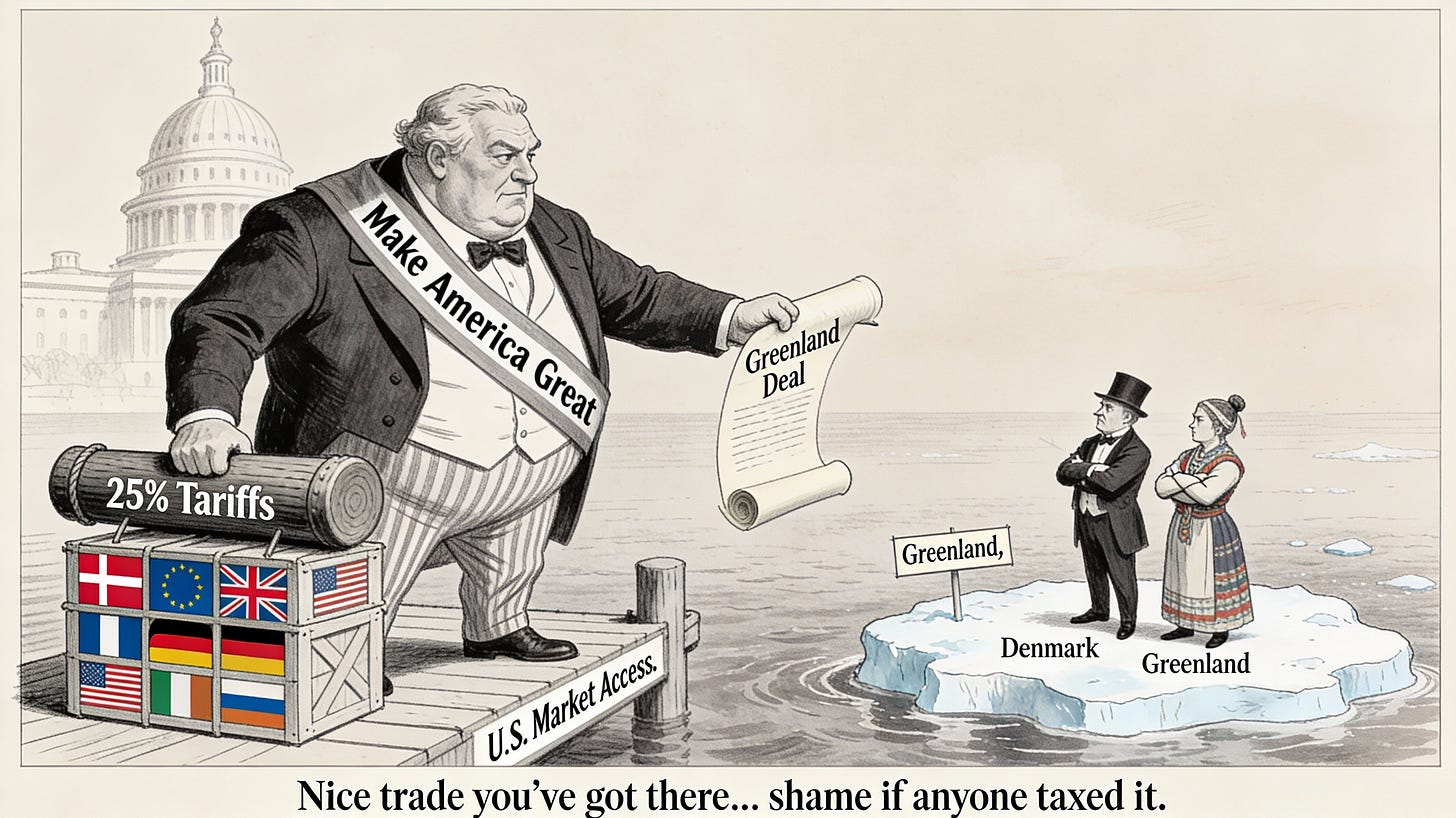

When a president threatens to hit his own allies with double‑digit tariffs unless they help him take an island they do not own, something deeper is broken than “trade policy.” What Donald Trump is now doing with Greenland is not just another round of tariff theater; it is the logical next step in the project I described in “The Greenland Grab: How America Would Trade a Liberal Order for One Island.” It is the move from tearing up norms on conquest to tearing up the economic order that made American power attractive in the first place.

In the span of a week, the White House has announced a 10 percent tariff on exports from eight European NATO allies—including Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Germany, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom—with a threat to raise that levy to 25 percent on June 1. The stated condition for lifting the tariffs is not an end to dumping, a subsidy program, or a security threat. It is, in the president’s words, “a fair and complete Deal” for the “Total purchase of Greenland.”

This is not a trade dispute; it is tariff blackmail aimed at forcing democratic partners to help Washington violate the very principles of sovereignty and self‑determination that America claims to defend. It takes the core illiberal impulse of the Greenland grab and runs it through the trading system.

From trade war to tribute demand

The numbers are, by now, depressingly familiar. A 10 percent across‑the‑board tariff on goods from eight advanced European economies would touch everything from German autos and machinery to Danish pharmaceuticals, Dutch chemicals, French wine, British aerospace components, and Nordic clean‑energy equipment. If Europe does not budge on Greenland by early summer, that surcharge automatically ratchets up to 25 percent.

What is different this time is not the scale of the tariffs, but their purpose. These measures are not being justified as retaliation for steel overcapacity, intellectual‑property theft, or national‑security concerns about critical minerals. They are being explicitly conditioned on a political concession: help the United States “reach a deal” to buy a giant chunk of Danish territory, over the opposition of Greenland’s own elected government, or watch your export sectors get slowly throttled.

In the first Greenland piece, the central claim was simple: a liberal hegemon that invades or seizes land from a fellow democracy breaks the very order that makes its hegemony useful. A system built on voluntary bargains and predictable rules cannot survive if the anchor state decides that some of those rules do not apply when it really wants something.

Tariff blackmail does the same kind of damage, through a different channel. If access to the American market can be yanked any time allies refuse to help Washington carry out an imperial real‑estate scheme, then trade agreements do not mean what they appear to mean. They become, at best, temporary indulgences—grants of low tariffs that can be revoked when the hegemon wants tribute.

Weaponized interdependence turned inward

Since at least the late 1940s, the story America has told itself and the world is that its economic and military power are constrained by rules. NATO, the GATT and WTO, the IMF and World Bank, the web of bilateral investment treaties—all of these were sold as ways of converting raw power into durable contracts. The United States would open its market wider than anyone else, extend security guarantees, and submit to common procedures in exchange for a world where other states felt safe plugging themselves into U.S.‑centric systems.

The result, as scholars of “weaponized interdependence” have noted, is a network in which the hegemon inevitably sits at key choke points: the dollar, SWIFT, major banks, tech platforms, critical supply chains. In the liberal narrative, those choke points are insurance policies—tools to discipline outright aggression, sanction rogue actors, and backstop the system when it is under stress.

The Greenland tariffs are the nightmare inversion of that story. Precisely because Europe is deeply intertwined with the American economy, that interdependence becomes a lever—not to defend an ally under attack, but to pressure that ally and its partners into facilitating a land grab.

If Washington is willing to weaponize trade in order to coerce Denmark and Greenland into handing over territory, then interdependence has stopped being a shield and become a vulnerability. The lesson for every other state is straightforward: the more integrated you are with the U.S. market, the easier it is for a future administration to use tariffs as a club whenever you refuse to play along with its most illiberal impulses.

That is exactly the kind of dynamic the earlier article warned about when it argued that a hegemon that treats rules as optional should not be surprised when everyone else starts looking for alternatives to its money and its courts.

The triple cost: alliances, prosperity, and the dollar

The immediate damage from tariff blackmail over Greenland falls along three dimensions: security alliances, shared prosperity, and the monetary‑financial order.

First, alliances.

Those words matter. It was one thing for European leaders to grit their teeth through aluminum and steel tariffs dressed up as national‑security measures, on the theory that this was a passing tantrum. It is another to be told: betray your own principles on territorial integrity and colonialism, or see your exports to the United States taxed into oblivion.

Once the price of honoring a fellow democracy’s sovereignty is a 25 percent tariff on cars, machinery, and pharmaceuticals, it becomes dramatically harder for those leaders to sell cooperation with Washington on Russia, China, and Arctic basing to their own voters. The U.S. is no longer just a sometimes‑clumsy security guarantor; it is a country willing to punish its allies for following their own laws and values.

Second, prosperity.

Tariffs are not paid by foreign governments; they are paid by importers and, ultimately, consumers and workers on both sides of the border. A 10–25 percent tax on European goods will show up in higher prices for American households and firms, disrupted supply chains, and lost sales for European exporters. Industry groups on both continents are already warning that another round of tariffs will cost jobs and investment, on top of the distortions from the last trade war.

What makes this episode particularly perverse is the underlying objective. Americans are not being asked to bear those costs in order to deter aggression, shore up an ally, or protect a critical technology. They are being conscripted—without being asked—into subsidizing a speculative imperial real‑estate play in the Arctic, complete with hints of military action “if necessary” if Denmark and Greenland continue to say no.

For a liberal hegemon, this is exactly backward. In a liberal order, wealth comes from consent and exchange, not conquest plus hidden taxes on your own citizens. Using tariffs as a lever for annexation is the economic equivalent of financing empire with a regressive war tax.

Third, the monetary‑financial order.

The U.S. dollar’s central role in global finance, and the preference for U.S. courts and law in cross‑border contracts, rest on more than size. They rest on a belief that the United States will be, most of the time, a predictable and lawful counterpart. If the leading power routinely uses its centrality in trade and finance to coerce law‑abiding allies into violating their own red lines on sovereignty, those allies acquire a structural incentive to diversify away.

No one should expect a swift “de‑dollarization” in response to Greenland tariffs. But every time Washington turns the trading system into a mechanism for tribute, it strengthens the arguments of those who want new payment systems, new legal venues, and new supply chains that do not run through the United States. That is not some abstract future risk; it is already visible in the way Europe and other partners have explored workarounds for U.S. secondary sanctions and dollar‑based restrictions.

From club goods to a protection racket

The deeper problem with the Greenland tariff gambit is not that it is clumsy or economically costly, although it is both. It is that it changes the category of what American power is.

For most of the postwar era, the U.S. tried to act like the manager of a club. Members paid dues—higher defense spending, lower tariffs, some alignment with U.S. security preferences—and in return received club goods: security guarantees, access to a huge and relatively open market, the stabilizing presence of the dollar and U.S. institutions. Disputes were inevitable, but they were supposed to be channeled through rules and organizations that gave everyone some voice.

A protection racket works differently. In a racket, the “protector” threatens to hurt you unless you pay up or hand over what he wants. The harm is not a side effect; it is the point. The Greenland tariffs are structured that way. The administration is not saying, “We regret this, but your subsidies leave us no choice.” It is saying, in effect: nice export sector you’ve got there—shame if anything happened to it while you stand in the way of our Arctic ambitions.

Once market access is framed as a hostage Washington can take whenever allies resist its more unhinged projects, the whole logic of the liberal order collapses. Why sign a long‑term trade deal with someone who reserves the right to rip it up if you will not help him take somebody else’s territory? Why tie your supply chains and legal system to a hegemon that openly treats interdependence as leverage for bullying, not as a mutual insurance policy?

In the earlier essay, the worry was that America was drifting from a contractual hegemon—first among equals in a voluntary order—toward a straight‑up empire that “takes what it wants and lets the lawyers clean up later.” The tariff offensive completes that drift on the economic side. It is what happens when the hegemon remembers that the club also owns a lot of baseball bats.

The liberal alternative

There is a temptation, even among some critics, to treat all of this as mere bargaining: Trump as the “disruptor” who uses tariffs as a cudgel to get a better price, a better basing deal, a better share of Greenland’s minerals. That misses the point. A liberal order is not one in which the strongest country always gets its way at the cheapest possible price. It is one in which some ways of getting your way are off the table, even when they would “work.”

Security gains that depend on tearing up trade agreements and punishing fellow democracies for protecting their own sovereignty are not gains. They are rebranded losses—for NATO cohesion, for economic prosperity, and for the long‑term credibility of the United States.

A genuinely liberal Arctic and trade strategy would move in the opposite direction. It would deepen cooperative defense arrangements with Denmark, Greenland, and other NATO allies, reinforcing existing agreements like the 1951 U.S.‑Denmark defense treaty and its recent updates rather than threatening to walk away. It would use trade, investment, and joint ventures to access Greenland’s resources on negotiated, consent‑based terms, on a timetable set by Greenlanders themselves. And it would treat U.S. reputation as a scarce asset, worth more than any marginal mineral deposit or base access that could be extorted via tariffs.

The first Greenland piece ended with a simple claim: the real test of American greatness is not whether it can plant a flag on more ice, but whether it can remember that Greenland—and every other place on the map—belongs, first, to its people. The tariff campaign adds a new test.

The question now is whether the United States wants to be trusted more than it wants to be feared. A country that uses its market as a weapon to shake down allies for territory has made its choice. A liberal hegemon would make another better, more inclusive choice.

Here is another point of view from George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin:

https://reason.com/volokh/2026/01/18/trumps-plan-to-seize-greenland-is-simultaneously-evil-illegal-and-stupidly-counterproductive/