The Quiet Death Trap

How courts, jails, and housing providers keep killing people we already know how to save

People leaving jail or prison with opioid use disorder face a risk most of us cannot fathom. In some places, they are more than one hundred times more likely to die of overdose in the weeks after release than the general population. This is not a mystery. We know why it happens, and we know how to prevent most of these deaths.

Medications for opioid use disorder—methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone—cut overdose risk dramatically when continued through custody and after release. Recovery housing that accepts people on these medications and provides structure, peer support, and case management improves outcomes across the board. Diversion to treatment instead of jail can interrupt the cycle entirely for many people with OUD.

Yet in jurisdiction after jurisdiction, the same deadly pattern repeats: MOUD is stopped at intake or never offered at all. Recovery homes refuse residents on medication. Diversion is narrow, inconsistent, and often reserved for those least in need. People cycle through jail, lose housing, and die.

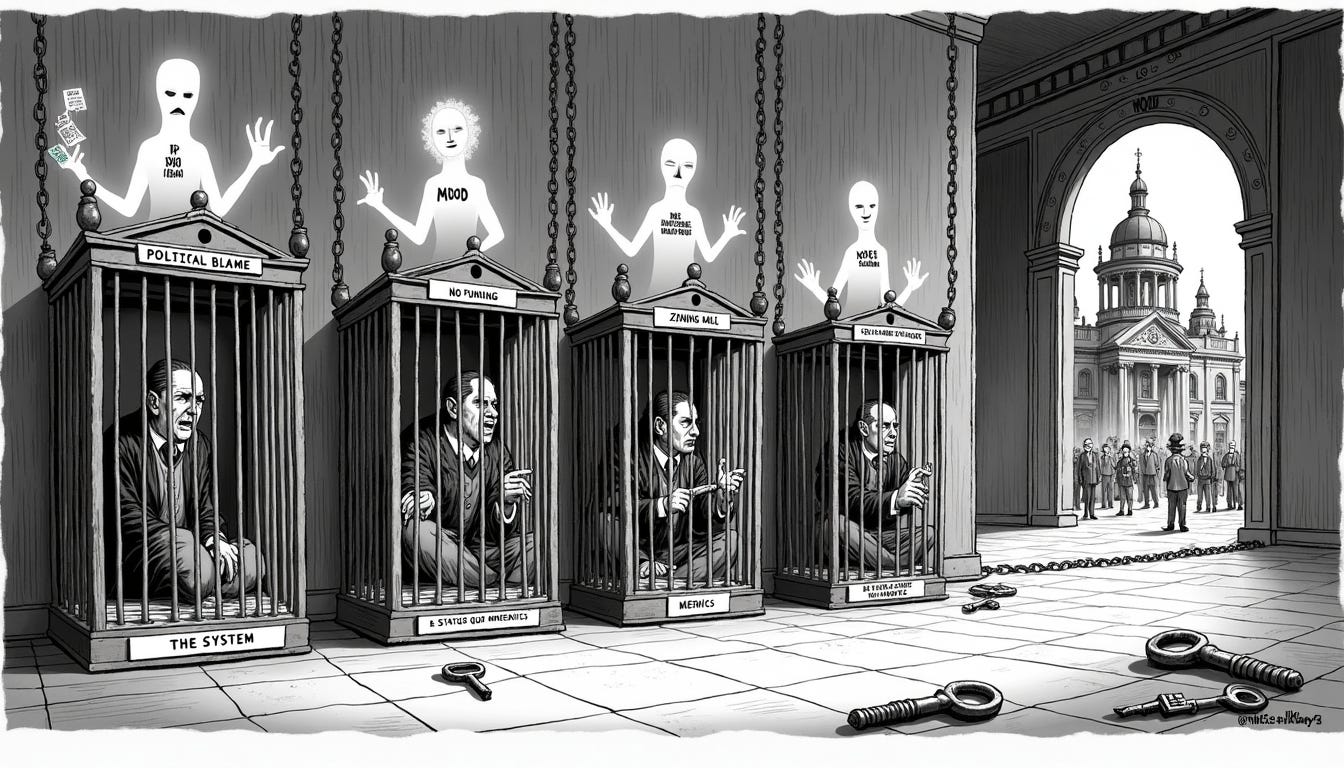

It is tempting to think the problem is ignorance or cruelty—that decision-makers simply do not know the evidence or do not care. But that is not the whole story, and it is not a useful story if we want to fix the system. The real problem is incentives and information. Courts, jails, housing providers, and state agencies are all making choices that seem reasonable from their own perspectives. But when you put those choices together, the system settles into a pattern that kills people even though a better pattern is available and would work.

The punishment trap

Think about the actors in this system and what they face.

Judges and prosecutors decide who gets diverted to treatment and who gets processed in the usual way. They know that if they divert someone and that person commits a serious crime, they will face harsh public criticism—editorials, recall campaigns, angry families appearing on the evening news. But when someone dies of overdose after being sent to jail where their MOUD was stopped? That death is quiet. It happens off-camera, in a motel room or a parking lot. No one connects it back to the judge’s decision. The asymmetry is stark: visible blame for rare, horrible crimes versus invisible nonblame for predictable, preventable deaths.

Jails and prisons may want to provide MOUD, but it requires coordination with outside providers, staff training, and funding that may not be there. And when someone overdoses a week after release, the facility does not feel that cost directly. The easier, “safer” path—administratively and politically—is to maintain abstinence-only policies and let someone else deal with the consequences.

Recovery housing providers worry about neighbors, zoning battles, and liability. Some have sincere beliefs about abstinence-only recovery rooted in older treatment models. Others simply find it simpler to ban people on MOUD entirely, even though those residents would be safer with medication than without it. The providers are not thinking about the statewide overdose rate; they are thinking about their lease, their funding stream, and the complaints they will get if something goes wrong.

State agencies fund what they have always funded, measure what they have always measured, and leave gaps in coverage that no single actor can fill alone. If MOUD in corrections is not a budget line item, if recovery housing certification does not require MOUD-inclusive policies, if performance dashboards track bed days and case processing times instead of overdose and continuity of care, then the system will keep producing the outcomes it is designed to produce.

Each actor is doing something defensible given their constraints. But the combined result is a punishment equilibrium: little MOUD in custody, abstinence-only housing, narrow diversion, high overdose, cycling through jail. The system is stable not because it works well, but because it feels safe to each participant individually—even though it is deadly collectively.

There is a better equilibrium

Now imagine a different pattern—one where the pieces actually fit together.

MOUD is the default in jails and prisons. People who come in on medication stay on it when clinically appropriate. People who need it get assessed and started on it. Release planning includes a guaranteed appointment with a community MOUD provider, plus help with transportation, prescriptions, and linkage to housing.

Recovery housing is MOUD-inclusive. Residents on medication are welcomed, not excluded. The housing provides peer support, case management, and help with basics like work, benefits, and staying connected to treatment.

Diversion is routine for people with OUD who meet basic criteria. Instead of processing them through standard criminal channels, courts default to connecting them with treatment and housing, with clear guidelines for when that is not appropriate and transparent reporting on outcomes.

In this harm-reduction equilibrium, overdose deaths plummet. People stay connected to treatment longer. Housing is more stable. Even recidivism improves because people are not being set up to fail by policies that strip away the medication keeping them alive.

The evidence shows this pattern works. Rhode Island implemented comprehensive MOUD across its corrections system—continuing medication for people already on it, offering it to those who need it, linking everyone to community care at release. Post-incarceration overdose deaths dropped by sixty-one percent. Statewide overdose mortality fell by twelve percent. Massachusetts ran jail-based MOUD pilots and found higher community treatment engagement plus lower overdose and all-cause mortality after release. Recovery housing studies show that MOUD-inclusive programs improve abstinence, retention, and employment outcomes without increasing overdose or crime risk in the residence.

So why does not every state just do this?

The puzzle

Here is the thing: in the model I built for a working paper on this question, the harm-reduction equilibrium is better for almost everyone.

It is better for funders and state agencies, who pay less in the long run for emergency services, incarceration, and crisis interventions.

It is better for judges and prosecutors, who see fewer overdose deaths and no increase—often a decrease—in serious crime.

It is better for housing providers, who have more stable residents and better long-term outcomes.

It is better for people with OUD, who are far less likely to die and far more likely to stay housed and out of jail.

And yet the punishment equilibrium persists.

Why? Because the punishment equilibrium feels safer to each actor individually, even when it is worse collectively.

When judges are punished heavily for rare but visible crimes by diverted individuals but almost never held accountable for predictable overdose deaths following MOUD discontinuation in custody, the politically safe move is to divert less and defer to incarceration.

When jails are not fully reimbursed for MOUD and do not directly pay the price of post-release overdose, the administratively safe move is to maintain abstinence policies and avoid the coordination costs.

When recovery homes worry about neighbors, funding, and the risk of one bad incident dominating local news, the path-of-least-resistance move is to exclude people on MOUD and stick with the model they know.

This is what economists call a coordination problem. Everyone would be better off in the harm-reduction equilibrium, but no single actor can get there alone, and the default gravitational pull of institutional caution and asymmetric information keeps dragging everyone back toward punishment.

The good news is that we do not need to rewrite criminal law or wait for a cultural revolution. We can move from punishment to harm reduction by changing how we fund, measure, and structure defaults. That is mechanism design—the quiet art of arranging incentives so that when people follow their own interests, the result is what we actually want: fewer deaths, more stability, and a system that does not betray the people it is supposed to help.

What comes next

In the next post, I will walk through how the punishment equilibrium actually works in detail—how the incentives lock in, why small differences in funding and blame structures can trap a whole system in a deadly pattern, and what the formal model reveals about the conditions under which harm reduction becomes stable.

Then we will look at the tools states and counties already have to flip the system: MOUD-inclusive funding commitments, performance-based transparency that tracks what actually matters, and simple changes to defaults that make the safer path the easier path. These are not radical ideas. They are applications of basic incentive theory to institutions that are, right now, producing outcomes no one defends and almost no one wants.

The people dying in motel rooms and parking lots after release are not strangers. They are someone’s child, someone’s parent, someone’s friend. The system killing them is not an accident of nature. It is a design we can change.