The Myth That Won’t Die

What Heritage’s own fraud database reveals about incentives, institutions, and the persistence of a political myth

A crisis in search of evidence

Every election cycle, Americans are told that undocumented immigrants are voting in large numbers and that this hidden wave of “illegal ballots” threatens the legitimacy of our democracy. The rhetoric is familiar: warnings about “non‑citizens on the rolls,” allegations that elections are being “stolen,” demands for ever‑stricter identification rules. The strongest conservative effort to document election fraud unintentionally shows that undocumented voting is not an electoral threat but a statistical mirage.

If those stories were true at scale, the data would already show it. Prosecutions would stack up, audits would routinely uncover large numbers of ineligible voters, and the institutions most invested in documenting fraud would have overflowing files. Instead, when you look at the record carefully, you see something very different: a gigantic election system in which non‑citizen voting of any kind is extremely rare, and confirmed cases involving undocumented immigrants are almost nonexistent.

One of the clearest windows into this reality comes from an unlikely source: the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that has spent years arguing that U.S. elections are vulnerable to fraud and pushing for tighter restrictions. This essay views the non-citizen voting debate as a form of institutional equilibrium, in which incentives drive behavior and the stories surrounding that behavior.

Not a study—and not a ceiling

Defenders of the fraud narrative respond in two ways. First, they emphasize (correctly) that Heritage’s database is not comprehensive: it records only those cases that were detected, formally handled, and then captured by staff. Second, they argue that the database therefore shows only the “bottom floor” of fraud, not the ceiling.

From a purely statistical perspective, that is right: you cannot treat Heritage’s tally as the upper bound on all non‑citizen voting. Detection is imperfect; some cases are never prosecuted; local reporters miss stories. There will always be incidents that never make it into any database.

But if you think in terms of incentives and behavior, the database is still incredibly informative. It is the product of a long‑running, highly motivated search by an institution that wants to find fraud. If there were truly a large amount of undocumented voting happening, this is exactly the kind of effort that should be able to document it.

Instead, what we see in Heritage’s own numbers is a pattern consistent with a very different world: one where non‑citizen and undocumented voting do occur, but at microscopic rates relative to the scale of American elections.

A game of incentives, not just rules

This is less a story about individual bad actors than about institutions responding rationally to asymmetric incentives. Why would the true rate be so low? The simplest answer is that the incentives point that way.

For a non‑citizen—especially an undocumented immigrant—the potential benefit of voting illegally is minuscule. One ballot among millions only infinitesimally changes the chance that a preferred candidate wins. The potential cost, however, is enormous: detection can mean fines, felony charges, loss of lawful status, and deportation. For most non‑citizens, risking deportation for a single ballot is not an abstract calculation; it is a frightening gamble.

At the same time, the institutional environment is not as porous as casual rhetoric suggests. Over the past two decades, states have added voter‑ID requirements, cross‑checks with citizenship databases, and more frequent audits. Even where those systems are imperfect, they raise the probability of detection enough that the expected cost of a fraudulent vote for a non‑citizen swamps the expected benefit.

On the enforcement side, officials face the opposite incentives. The marginal benefit of detecting one more fraudulent vote in terms of actual election outcomes is essentially zero; the odds that any single illegal ballot changes a result are tiny. But the political payoff from uncovering and publicizing even a handful of cases is large. Elected officials and advocacy groups can point to those cases to push legislation, mobilize donors, and energize base voters.

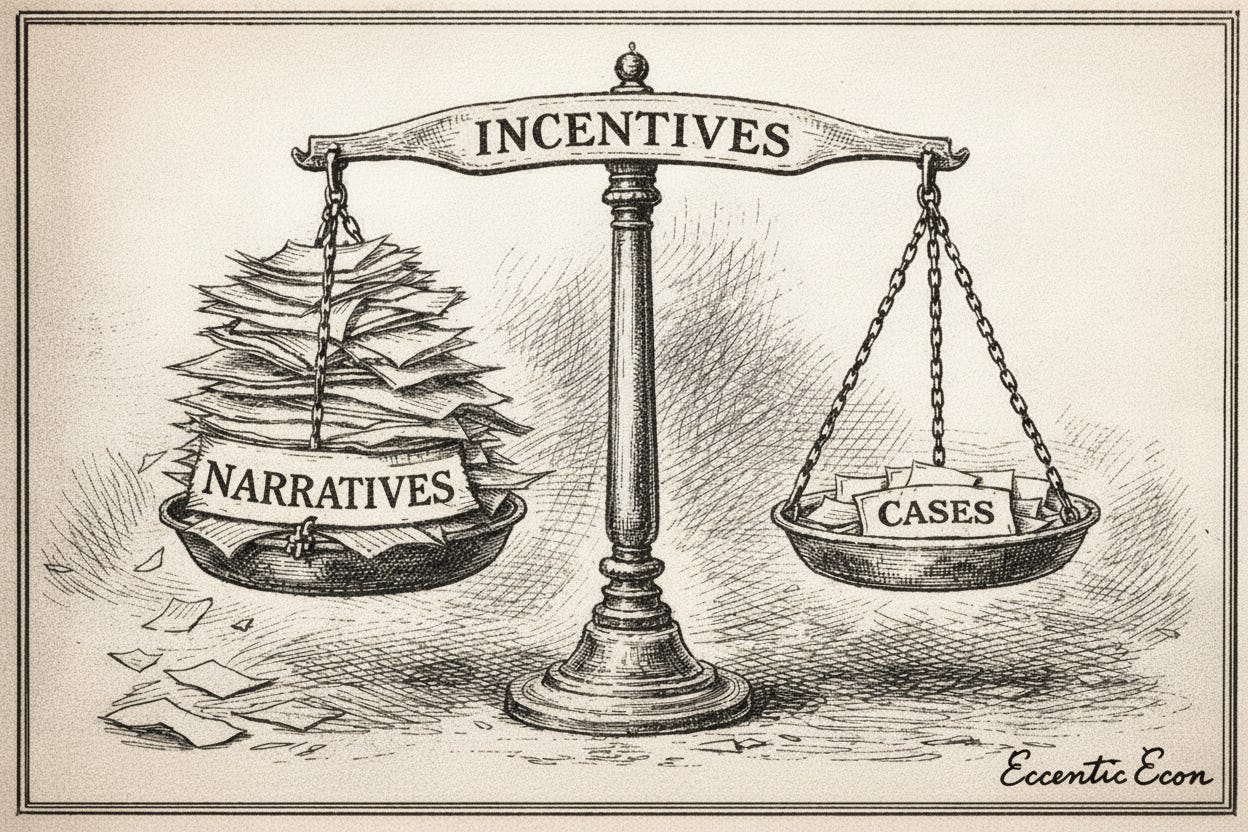

Put together, that mix of incentives leads to exactly the pattern we see:

Non‑citizens almost never attempt to vote illegally because the risk‑reward ratio is wildly unfavorable.

Politicians and advocacy organizations over‑invest in searching for and amplifying the rare cases they can find, because those cases are rhetorically valuable even when they are numerically insignificant.

Heritage’s database is the natural output of that environment: a small collection of highly salient stories, repeatedly cited as proof of a crisis, even though taken together they amount to a rounding error in the denominator of all ballots cast.

Institutional design for the world we actually have

None of this implies that election rules don’t matter or that we should ignore fraud. The state has a legitimate interest in keeping non‑citizens from voting in federal and most state elections, and sensible safeguards—clear eligibility rules, basic identity checks, and routine audits—are appropriate.

The real policy question is margin management. When the best available evidence, including from groups ideologically committed to finding fraud, shows that proven non‑citizen and undocumented voting are extraordinarily rare, what kinds of interventions are justified?

One approach is to treat even a tiny number of non‑citizen votes as justification for sweeping new requirements: documentary proof of citizenship to register, aggressive voter‑roll purges based on flawed databases, or national ID mandates. Those measures may marginally reduce an already microscopic risk, but they also raise the cost of participation for lawful voters and increase the risk of erroneous disenfranchisement.

Another approach—the one more consistent with both the data and the incentive story—is to tighten where errors actually occur, without building policy on imagined waves of undocumented voters. The American Immigration Council’s analysis points out that many of the non‑citizen voting cases in Heritage’s database originated in government error: officials wrongly encouraged non‑citizens to register or failed to check documentation properly. Better training for front‑line staff, clear communication about eligibility, and modest investments in record‑keeping do more to prevent these rare mistakes than sweeping new barriers aimed at a crisis that isn’t there.

In a constitutional political‑economy sense, that matters. The power to regulate elections and determine who counts as a legitimate voter is one of the most dangerous tools a state wields. It should be exercised with restraint, grounded in evidence rather than fear. When the evidence—especially the evidence painstakingly collected by those most eager to prove a problem—shows that a particular form of fraud is almost nonexistent, the burden of proof shifts to the would‑be restrictors.

The real lesson of Heritage’s numbers

The Heritage Foundation set out to build a flagship resource documenting election fraud in the United States. In some ways, it succeeded: the database is detailed, searchable, and politically influential.

Yet when you read it with a clear eye and a calculator, it ends up telling a very different story from the one its sponsors intended. Across decades of elections and more than a billion ballots, Heritage’s own data show only dozens of non‑citizen voting cases, including a bare handful involving undocumented immigrants. Other audits and investigations in key states reinforce the same conclusion: non‑citizen voting happens, but at rates so low that they cannot plausibly explain electoral outcomes.

For readers who care about how institutions behave under pressure, that pattern is not a reason for complacency. It is a reason for clarity. The system we have built—imperfect, decentralized, and often messy—has produced an equilibrium in which undocumented voting is the exception, not the rule. More broadly, this is what institutional equilibrium looks like when rare events generate high political returns—narratives persist even when the underlying rates remain negligible.

That should shape how we design the next round of rules. It should temper the calls for ever‑harsher restrictions that fall hardest on lawful voters.

I’m curious whether readers see incentive or institutional dynamics that point elsewhere; frameworks like this are strongest when tested against what others actually observe.

Great post