The Economics of Paranoia: Why Great Replacement Theory Is Incoherent on Its Own Terms

A conspiracy dressed up as labor economics—and why the numbers never add up

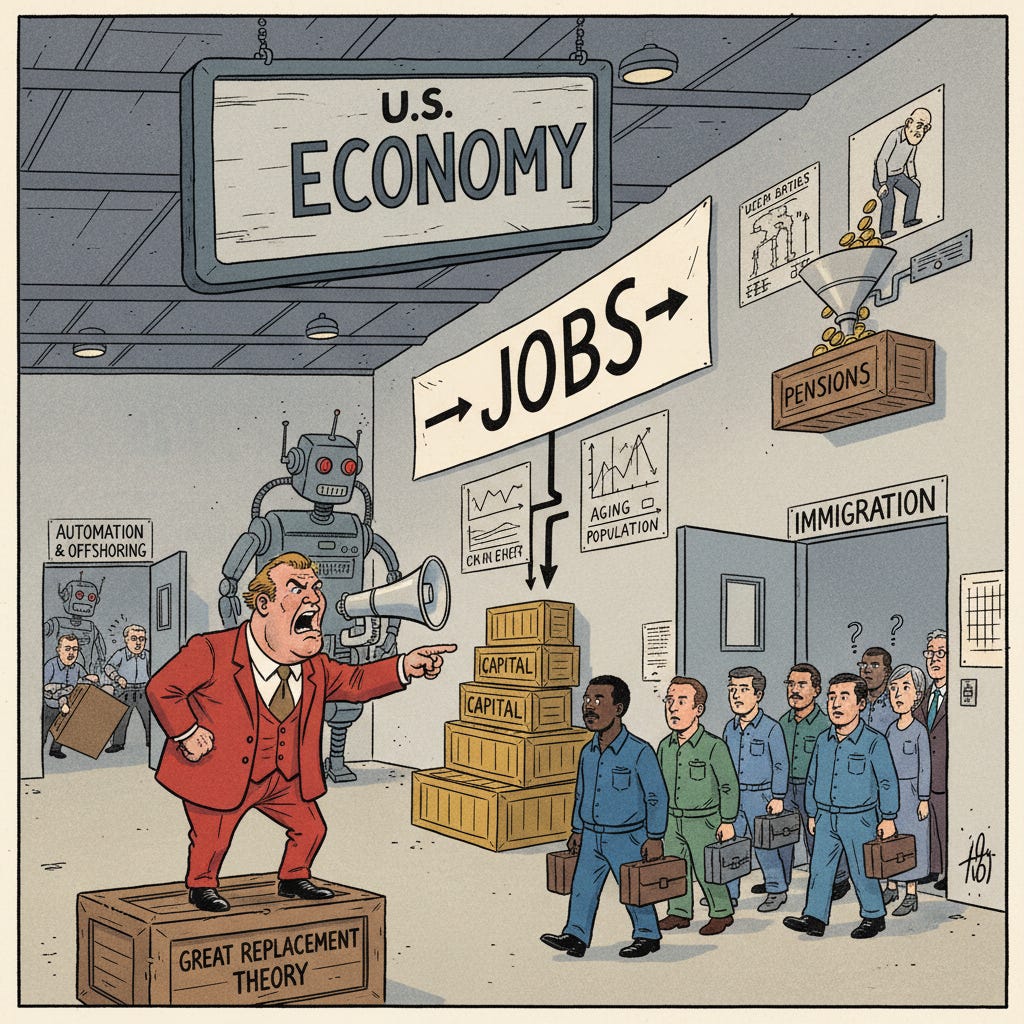

Voters are being sold a conspiracy theory where an economic argument should be. Great Replacement theory is not just poisonous politics; it is profoundly confused about how labor markets, public finance, and growth actually work. The tragedy is that it takes real dislocation and anxiety and channels them into a story that is emotionally satisfying, intellectually lazy, and economically backwards.

For years, the “great replacement” lurked on the racist fringes: anonymous message boards, manifestos posted just before mass shootings, the usual fever swamps of ethnic grievance. Today it comes lacquered with respectability. Former Fox News host Tucker Carlson turned it into a recurring segment, warning millions of viewers that Democrats were deliberately “replacing” native‑born Americans with more compliant immigrant voters. Analyses of his show documented hundreds of episodes pushing some version of that narrative, often framed as a sober demographic observation rather than the paranoid fantasy it is.

He is hardly alone. Rep. Elise Stefanik has run ads decrying a supposed “permanent election insurrection” via immigration, language straight from the replacement playbook. JD Vance, Matt Gaetz, and other MAGA‑aligned Republicans have echoed the claim that immigration policy is really an electoral heist conducted by Democrats. Abroad, politicians from Marine Le Pen in France to Thilo Sarrazin in Germany have sold variations on the same story: a native population under siege by demographic engineering from above. Once that rhetoric reaches debate stages and campaign ads, it acquires a policy patina it has never earned.

Under the gloss, the basic structure is simple. Great Replacement theory claims that shadowy “elites” are deliberately importing non‑white, non‑Christian immigrants to erase native‑born whites from their own countries. Demographic change becomes dispossession; immigration becomes a plot; economic anxiety becomes proof of a coordinated campaign to “replace” one population with another. It is an attempt to turn the ordinary churn of a dynamic, open society into a slow‑motion coup.

To make this story sound plausible, its advocates lean heavily on a few key economic claims:

· Immigrants “steal” jobs and drive down wages for natives.

· Immigrants overload welfare states and drain public coffers.

· Immigrants dilute the political and cultural power that rightly “belongs” to natives and thus threaten their economic position.

The moral rot in this worldview is obvious enough. Less obvious, but just as important, is that every one of these claims falls apart once you apply the sort of basic economics that used to be mainstream on left and right alike.

The jobs that keep getting “stolen”

The first problem is an old fallacy dressed up in new language: the fixed‑pie view of employment. If you assume there are only so many jobs, then every additional worker looks like pure competition. Under that assumption, it is easy to tell a story where a native worker loses whenever an immigrant arrives. The rhetoric of “replacement” simply racializes this old lump‑of‑labor fallacy.

Market economies do not work that way. Every worker is also a consumer, a renter, a driver, a neighbor, and often an entrepreneur. Immigrants do not just supply labor; they rent apartments, buy food, start firms, and pay taxes. A meatpacking plant that hires refugees is also selling to the communities those refugees help enlarge. A construction firm that employs Mexican laborers is also responding to the demand for housing that those workers, and others, create.

Capital reacts, too. When a region attracts more potential workers and customers, businesses invest more there: new equipment, new buildings, new lines of production. That capital deepening creates additional jobs over time. The very same dynamic that replacement theorists describe as “they are coming to take your job” is, in standard labor‑market language, a shift that can expand both employment and output if institutions allow wages and investment to adjust.

When native mid‑skill workers in rich countries got squeezed, the main competition was not a newly arrived immigrant. It was a robot, a software package, or a factory that decamped to a lower‑wage country. Routine, codifiable tasks are precisely the ones that automation and offshoring have eaten first. Immigration makes an easy scapegoat because it is visible and human. Machines and trade agreements, by contrast, do not show up in your neighborhood looking for a place to live.

There is an irony here. Many of the most vocal defenders of Great Replacement narratives also claim to revere markets. Yet on this question, they quietly swap out a dynamic model of labor and capital for a static one where nothing adjusts, no one moves, and every new person is a threat. The story requires economic illiteracy to function.

The fiscal math runs the other way

If the jobs story is built on a misunderstanding of basic labor economics, the fiscal story is built on a misreading of arithmetic. Replacement theorists insist that immigrants come to plunder generous welfare states, and that this inflow will bankrupt social insurance systems. In their telling, the taxpaying “native” is the mark, and the immigrant is the scammer.

Start with the actual demographic reality of advanced economies. Developed countries in Europe, East Asia, and North America are aging rapidly, with rising ratios of retirees to workers. Fertility in many of these societies has been below replacement for decades. Absent migration, populations decline and the tax base shrinks. That is not a speculative scenario; it is already visible in countries from Japan to Italy.

Under pay‑as‑you‑go systems, today’s workers finance today’s retirees. The arithmetic is unforgiving. You can keep benefits generous, or you can let the worker‑to‑retiree ratio fall, but you cannot do both indefinitely without raising taxes or borrowing heavily. A steady inflow of working‑age immigrants eases that burden; it does not worsen it. Immigrants who arrive as adults are fiscal assets for a long time, especially in systems where major benefits are linked to age rather than income.

Even low‑skill immigrants often pay more in taxes over their lifetimes than they receive in services, once you account for when they arrive, when they are most productive, and how social insurance is structured. They help finance the pensions and healthcare of aging natives who might otherwise face steeper benefit cuts or higher taxes. If your goal is to keep the promises made to current and future retirees, kneecapping immigration is about the worst strategy one could design.

The replacement frame inverts cause and effect. Rich democracies did not become fiscally fragile because too many immigrants arrived. They became fragile because they promised benefits premised on demographic assumptions that did not hold—assumptions about birthrates, life expectancy, and long‑run growth. Immigration is one of the few margins on which those assumptions can be adjusted in our favor.

Real pain, fake diagnosis

Great Replacement theory would be easier to dismiss if it were selling grievances to people whose lives were otherwise humming along. It is not. Many of the workers most receptive to replacement rhetoric have, in fact, watched their relative economic position erode. Factories closed; union bargaining power collapsed; small towns lost anchor employers and never recovered. Stagnant wages, shuttered main streets, and a sense of lost dignity are not hallucinations.

The question, then, is not whether the pain is real but what caused it—and what, if anything, can realistically remedy it.

Here the story starts to look familiar. The major culprits are impersonal but powerful:

· Automation that made it profitable to substitute machines and software for routine labor.

· Offshoring and global competition that exposed previously sheltered firms to lower‑cost rivals abroad.

· Domestic policy choices—on education, zoning, licensing, trade, monetary policy—that made adjustment harder than it needed to be.

These forces implicate institutions. They invite arguments about trade rules, tax structures, labor law, school quality, housing supply, and how central banks respond to shocks. None of that makes for a viral segment. It is easier to tell a morality play in which “real” citizens are being sold out to “invaders” by a corrupt elite.

Great Replacement theory offers precisely that. It trades institutional analysis for a cartoon. It tells hurting workers that their main problem is people who look different and speak another language, not the policy environment that amplifies or mitigates economic shocks. It invites them to focus on where their new neighbors were born, rather than on why it is so hard to start a business, move for opportunity, build housing, or retrain later in life.

Economically, that is upside‑down. When you target immigrants instead of the rules that shape investment, innovation, and mobility, you aim your policy firepower at the wrong mechanism. You can close borders without resurrecting a single factory town. You can harass asylum seekers without bringing back the old wage premium for routine manufacturing work.

Policies that backfire

Bad diagnosis leads to bad prescriptions. If you treat demographic change as a plot, you will call for punitive immigration restrictions and proposals to boost “native” fertility as a substitute for migration. You will dress up the old nativist dream—fewer foreigners, more babies from “our” people—as an economic development plan.

Those ideas do not just fail on their own terms; they actively aggravate the economic problems their advocates claim to worry about.

Consider the likely consequences:

Meanwhile, the romantic notion that governments can engineer a rapid native‑born baby boom runs into biology and time. Even if fertility incentives worked, children take decades to become taxpayers. Advanced economies simply do not have that kind of time to repair the balance sheets of their social insurance systems. You cannot plug a pension shortfall in 2035 with babies born in 2028.

The irony is sharp. A movement that markets itself as the guardian of Western prosperity pushes policies that lock in slower growth, tighter fiscal constraints, and more brittle labor markets. That is not economic nationalism; it is economic self‑harm.

Fear in place of analysis

There is a recurring temptation in politics to treat demography as destiny and culture as a zero‑sum game. That temptation grows stronger in moments of rapid change, when the world feels less familiar and less predictable. Great Replacement theory feeds on that unease. It tells people who feel unmoored that their story has a clear villain and a simple fix.

But once the conversation shifts from slogans to supply and demand, from vibes to balance sheets, the theory collapses. The labor‑market model it assumes is wrong, the fiscal math it invokes is backward, and the policy responses it demands would make existing problems worse. It is bad sociology draped over worse economics.

There are serious debates to be had about immigration levels, enforcement, and integration. There are real questions about how to share the gains from trade and technology more broadly, how to make opportunity less dependent on ZIP code, and how to honor the legitimate claims of communities that have borne the brunt of economic transition. Those are arguments worth having.

Great Replacement theory is not one of them. It is not a contribution to economic debate; it is an evasion of it.