No, Trump Did Not Win Davos

Niall Ferguson mistakes spectacle for statecraft

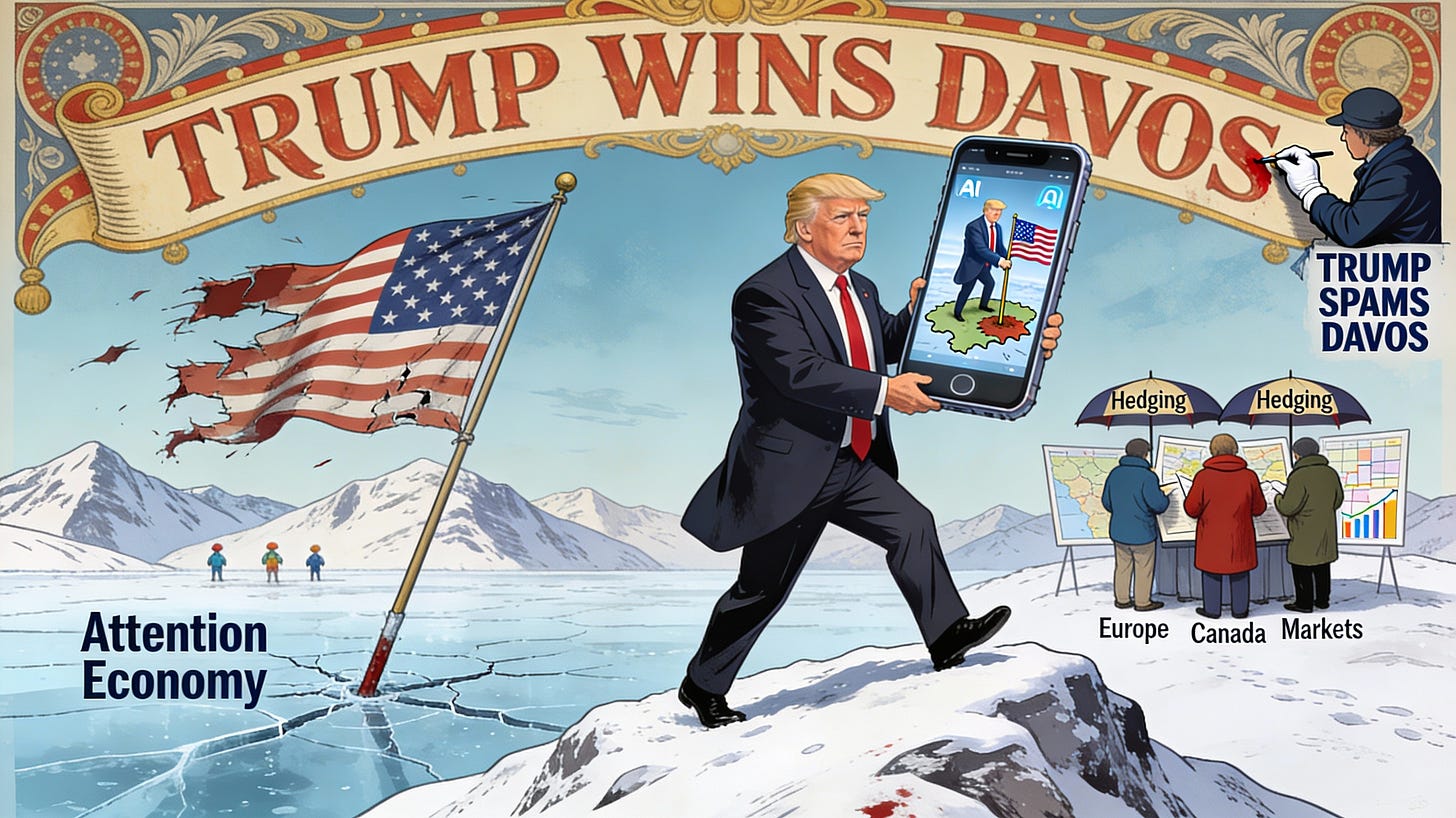

Niall Ferguson opened his recent essay by claiming he had “never before seen a single individual so completely dominate this vast bazaar of the powerful, the wealthy, the famous, and the self-important.“ He was right—Trump hijacked Davos 2026 entirely. But Ferguson then makes a leap that conflates attention with achievement: he concludes that by seizing the news cycle and spooking Europe into public capitulation, Trump “won” the conference.

This is precisely backward. If we measure victory by the ability to force every billionaire and foreign minister in the Alps to stare anxiously at their phones, Trump succeeded spectacularly. If we measure it by advancing American interests, stabilizing alliances, or establishing any durable policy architecture, he failed—loudly, repeatedly, and in full view of the global establishment he was supposed to intimidate into submission.

The problem with Ferguson’s analysis is not that it’s empirically wrong. It’s that he has confused dominating the attention economy with exercising power. The Davos class spent a week doom-scrolling Trump because they were terrified. But terror and compliance are not the same thing, and Trump’s week in Switzerland proved exactly why: every bluff, every escalation, every AI meme walked back into the same void of unenforceable threats and reversible commitments. Davos 2026 was not a victory for American power. It was a live demonstration of why the world is hedging away from it.

The Tariff Roulette

Start with the core absurdity: the escalation and collapse around Greenland.

Trump didn’t float a trial balloon about Arctic sovereignty or gently probe Europe’s appetite for a renegotiation of Cold War-era Greenland protocols. He simply announced on social media that he would impose a 10 percent tariff on eight European NATO allies—Denmark, Sweden, France, Britain, the Netherlands, and Finland—unless they agreed to sell Greenland to the United States. If they didn’t comply by June 1, he would escalate to 25 percent. Not a negotiation. Not a framework for discussion. A coercive demand backed by explicit tariff threats on allied nations.

Worse, the justification was pure protection-racket rhetoric. At Davos, Trump repeatedly invoked the tired trope that America pays for NATO—”the States was for virtually 100% of NATO,” he declared, a figure NATO’s own secretary general immediately refuted. Then the tone-shift: “Then if you don’t, I’m putting a 25% tariff on everything that you sell into the United States, and a 100% tariff on your wines and champagnes.”

But here is the part Ferguson treats as strategic brilliance: Trump didn’t follow through. After a meeting with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, he announced a “framework of a future deal with respect to Greenland“ that would involve further discussions about the 1951 treaty governing U.S. military presence on the island, plus vague language about NATO enhancing Arctic security. The tariffs were withdrawn. The acquisition demand was shelved. Greenland remained, as it had always been, a non-negotiable Danish territory.

Ferguson interprets this retreat as evidence that Trump “never had the remotest intention” of imposing tariffs—that the whole thing was a brilliant bluff designed to make Europe sweat and concede something. But this reading demands we accept that Trump’s team deliberately spooked global markets and allied governments with a threat they didn’t mean to keep, then patted themselves on the back for a “framework” that amounts to agreeing to talk later about slightly different security arrangements in the Arctic.

That’s not statecraft. That’s needlessly burning credibility.

Meme-Presidency as Foreign Policy

The Greenland debacle alone would be embarrassing. But Trump managed to pair it with a theatrical performance so divorced from traditional diplomacy that it ceased to be persuasion and became pure spectacle.

Consider the AI imagery. In the days before and after his Davos speech, Trump and the White House released a series of AI-generated images: Trump planting a flag on a reimagined U.S.-annexed Greenland, expanded maps showing Greenland, Canada, and even Venezuela under the Stars and Stripes, tableaus of Trump, JD Vance, and Marco Rubio standing triumphantly on new American territory. The message was clear: Greenland belongs to us, we just haven’t taken possession yet.

Then came the “Embrace the Penguin” gambit. As the meme took flight online, the official White House account posted an AI image of Trump walking through icy mountains alongside a “nihilist penguin” waving an American flag, with Greenland’s flag visible in the background, captioned simply: “Embrace The Penguin.”

To Ferguson and his admirers, this is proof of Trump’s mastery of modern media and his ability to keep the elite fixated on his narrative. To the European leaders and security officials actually tasked with managing the fallout, it was something else: evidence that the President of the United States conducts foreign policy in the same register as shitposting.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, called the tariff gambit a “mistake” that risked a “downward spiral” in U.S.–EU relations. She wasn’t reacting to a clever bluff that got her to capitulate. She was watching the U.S. President treat alliance commitments and territorial questions as props for TikTok theater.

The Strength of Unpredictability

Ferguson’s deeper move is to treat Trump’s admitted unpredictability as a feature, not a bug—to frame erratic behavior as a sophisticated negotiating tactic that keeps adversaries off-balance.

But there’s a problem: unpredictability only works as leverage if the threat is credible. The more Trump says things he doesn’t mean, the more the world learns to ignore him.

Consider what happened this week. European allies didn’t interpret Trump’s tariff threats as a brilliant feint designed to extract concessions. They interpreted them as noise—expensive noise that spooked markets briefly, but noise nonetheless. By the time Trump and Rutte emerged from their meeting claiming victory, the message being absorbed by every treasury, defense ministry, and corporate board room across NATO was not “Trump is a genius negotiator.” It was “Trump says things he doesn’t mean, so we should plan as if he isn’t there.” As a Council on Foreign Relations analyst observed, Davos participants “have only one country and one person on their mind: the United States and Donald Trump”—yet the practical response is not deference but more hedging, more bilateral workarounds, and less faith in multilateral forums with Washington at the center.

This is the perverse incentive structure of bluff-heavy diplomacy. Each failed escalation degrades the credibility of the next threat. A president who threatens tariffs and then backs down has not intimidated his counterparts; he’s trained them to expect that his threats will dissolve under pressure. When a real crisis arrives—a genuine conflict of interest where Trump actually means to follow through—the world will have spent years learning to discount his warnings.

Moreover, Ferguson glosses over why the threats were walked back at all. According to his own logic, Trump never intended the tariffs and Greenland was always a bluff. But polling released during Davos showed that only 10 percent of American voters supported taking Greenland by force, and 55 percent opposed even trying to buy it.[11] The “bluff” had to be abandoned not because it succeeded in extracting concessions from Europe, but because it was failing at home. That’s not genius; that’s a president who got ahead of his own political base and had to back down.

When Dominating the News Cycle Is Not the Same as Winning

Here’s the crucial distinction that Ferguson misses: controlling the attention of Davos and controlling the behavior of Davos are not the same thing.

Yes, every panel, every bilateral meeting, every WhatsApp exchange in the Congress Centre had to reckon with Trump’s Greenland demands and tariff threats. Yes, the event’s stated theme of “A Spirit of Dialogue” was entirely overshadowed by a president treating the conference like a reality-TV show. Ferguson is right that this is a kind of dominance.

But ask yourself what actually happened. European countries didn’t agree to sell Greenland or renegotiate NATO spending or capitulate on climate or abandon their own security strategies. What they did was huddle together more closely, accelerate their push for strategic autonomy from Washington, and begin the long process of building supply chains and security architectures that assume Trump, or someone like him, will be unpredictable indefinitely.

That is the opposite of winning. That is the observable behavior of a system in decline—a hyperpower that commands so little confidence that its closest allies are quietly but urgently planning for a world in which it cannot be relied upon.

The Policy Vacuum

To complete the indictment, Trump’s Davos appearance produced almost no substantive policy output. The World Economic Forum had billed his speech as an opportunity to discuss inflation, housing affordability, and the longer-term competitive challenges facing the American economy. Instead, the week was consumed entirely by Greenland theater, tariff feints, ad hominem attacks on “ungrateful” Denmark and a “not even recognizable” Europe, plus familiar riffs about immigration and the supposed “economic miracle” of his first weeks back in office.

The actual domestic agenda—the items that would matter for U.S. competitiveness and statecraft—barely registered. A “framework” is not a policy. A refusal to use force is not a concession extracted. An agreement to talk later about Arctic security is not a victory won.

The Real Winner

If you’re searching for who “won Davos,” look past Trump. The real victors were the European leaders who walked away with exactly what they started with—their countries’ sovereignty intact, their alliances strengthened by shared alarm, and a clearer rationale for their hedging strategy. They didn’t need to negotiate. They just needed to outlast the week and let Trump’s own contradictions do the work.

Niall Ferguson is a brilliant historian of power and finance. He understands the long view better than almost anyone writing today. But on this occasion, he has made a classic mistake: he has confused visibility with victory, attention with achievement, and a president’s ability to generate panic with his ability to translate that panic into policy wins.

Trump won Davos the way a wrecking ball dominates a building. Yes, he was the center of attention. Yes, he left everyone shaken. But at the end of the week, the structure was still standing, the allies were still allied (however nervously), and the world had one more data point confirming what it increasingly believes: that the United States is less a reliable partner than an unpredictable force to be managed, feared, and insured against.

If that’s what counts as victory in 2026, the bar isn’t just low anymore. It’s underwater—and the person drowning is us.