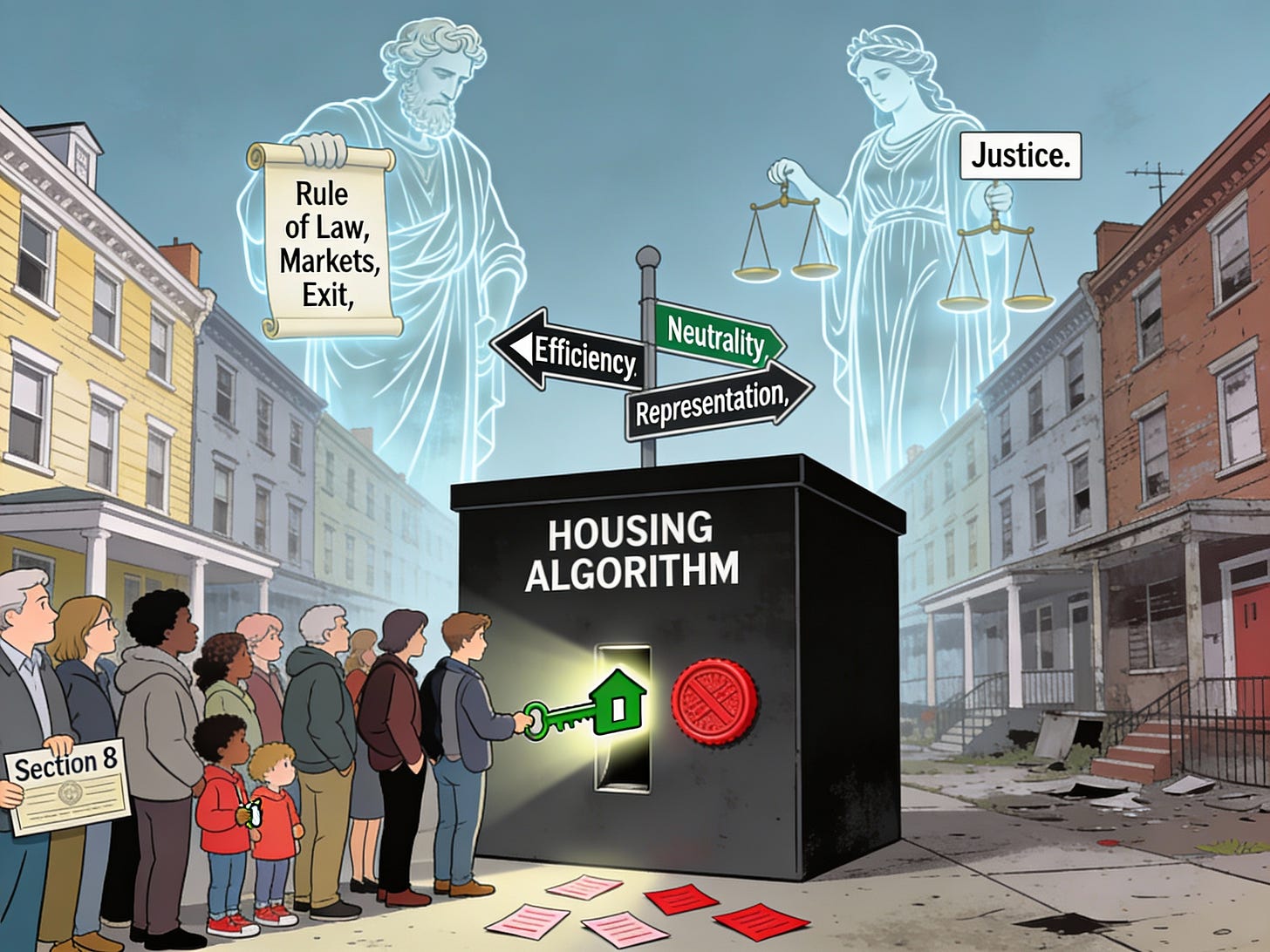

Liberty at the Algorithm’s Edge

How to pursue justice in housing markets when the math won’t let us be perfectly fair

When algorithms decide who gets a mortgage or an apartment, they are exercising power over people’s life chances. That is one reason this is an area where research of mine is currently moving toward peer review (not that there’s any set time frame for that…). The more the work develops, the clearer a classical liberal lesson becomes: justice in algorithmic housing markets is not about abolishing power, but about constraining and aligning it in systems that cannot satisfy every ideal at once.

When code becomes a gatekeeper

In today’s housing markets, the crucial “yes” or “no” often comes from a model, not a person. Credit-scoring engines and mortgage underwriting systems filter who even gets to the loan officer’s desk. Tenant-screening tools decide whether a voucher holder’s application ever makes it to a landlord. Advertising algorithms determine who sees which neighborhoods and which price points in the first place.

None of this happens on a blank slate, because none of the individuals creating the algorithms come to their jobs as a tabula rasa. The data feeding these systems comes from a world shaped by redlining, zoning designed to exclude, and decades of differential access to credit. Unsurprisingly, algorithmic systems trained on that history tend to reproduce it: Black and Latino applicants face higher denial rates, higher effective prices, and more “computer-says-no” moments than similarly situated white applicants.

A classical liberal should care about this, not because markets are inherently suspect, but because concentrated power—public or private—demands scrutiny. When owners of scarce housing, large lenders, and opaque software all line up on one side of the bargaining table, the presumption of healthy competition starts to wobble.

Three liberal values in conflict

The instinctive classical liberal response is to reach for three commitments at once.

· Rule-of-law neutrality. Decisions about housing credit should not depend on who you are. Rules should be general, predictable, and blind to race, ethnicity, or other protected traits.

· Market efficiency. Lenders and landlords should be free to use information to price risk, and to reject applications that truly pose high default or eviction risk, because mispriced risk undermines the capital formation and entrepreneurship that fuel prosperity.

· Robust individual agency. People, especially those historically shut out, should have genuine opportunities to improve their position—build credit, accumulate equity, move to better neighborhoods—and should not be trapped by opaque systems that render them invisible.

The difficulty, as the formal work under the hood shows, is that in unequal markets these three aims cannot all be maximized at once. When groups enter the process with different average risk because of past injustice, algorithms that perfectly track risk and treat everyone “the same” in form will almost inevitably translate that history into persistent gaps in access and wealth. Efforts to close those gaps—by tinkering with thresholds, adding constraints, or explicitly favoring disadvantaged groups—will either depart from pure risk pricing, abandon strict formal neutrality, or both.

The fairness trilemma, through a liberal lens

The model underlying my research makes this tension precise. It considers a world with two groups who differ in baseline default risk, a profit-maximizing algorithm that uses a common score cutoff, and a fairness-constrained algorithm that pushes approvals for the disadvantaged group up toward the advantaged group’s level at some cost in lender profit. Stakeholders—lenders, regulators, and group representatives—have different preferences over which algorithm governs the market.

From that setup, an Arrow-style impossibility result emerges. No rule for choosing between algorithms can simultaneously:

· Avoid picking algorithms that are strictly worse for everyone than some alternative (efficiency).

· Treat group labels as purely formal—swapping “Group A” and “Group B” in the model swaps nothing but names (symmetry).

· Guarantee that, in at least some environments, the disadvantaged side can secure inclusion of a fairness-enhancing algorithm when it raises their wealth without pushing the advantaged group below a reasonable floor (representation).

In plainer language: once algorithms have different effects on groups’ ability to build housing wealth, there is no institution that keeps markets fully efficient, treats everyone the same in form, and also gives marginalized communities strong, reliable leverage over how the system behaves.

For a classical liberal, this is not a cue to abandon markets or neutrality, but a reminder that justice in complex systems involves trade-offs, not perfection. Demanding all three values at once is a way to end up with none of them clearly defended.

Justice as constrained power, not technocratic utopia

So what does justice look like when the math refuses to give us a technocratic fix?

First, it means taking concentrations of algorithmic power seriously. When a handful of screening companies or lending platforms can, through their models, effectively decide who rents where or who accumulates equity, they function like quasi-regulators. Classical liberalism has always been wary of such private centers of power, especially when insulated from competition and transparency. Requiring model audits, contestable decisions, and clear channels for exit and appeal is not statism; it is the rule-of-law applied to new chokepoints.

Second, justice requires an honest choice about which constraint to relax:

· Relax efficiency: forbid certain profit-maximizing models or variables—say, those that encode past segregation too directly—even if that means higher measured risk or lower short-run profit. This is a recognition that not all mutually agreeable trades are just when one side’s bargaining position is built on yesterday’s coercion.

Classical liberalism does not supply an automatic answer here. It does, however, insist that the choice be made in the open, with institutions designed to keep both state and corporate power contestable.

Finally, justice in this frame is forward-looking. The goal is not to freeze today’s distributions or to hand central planners the task of allocating mortgages. It is to design governance for algorithms that widens genuine exit options, lowers artificial barriers to mobility, and lets more people participate in markets on terms that are not rigged by inherited disadvantage. That may sometimes mean tolerating less-than-perfect risk pricing, or endorsing narrowly tailored race-conscious tools, when the alternative is a status quo where the “neutral” algorithm quietly bakes yesterday’s injustices into tomorrow’s opportunities.

Liberalism after the black box

Much of the public debate about AI in housing focuses on opacity and privacy—the “black box” and the data it consumes. Those concerns are real. But the deeper problem for a classical liberal is that the box sits atop a landscape where some people have many ways out and others have very few. When a family’s access to decent housing, good schools, and a shot at equity depends on the verdict of a proprietary model trained on skewed history, the old questions about liberty, power, and justice reappear in new guise.

The research this article grows out of does not solve those questions; it simply shows that they cannot be delegated to clever code. Any algorithmic governance regime in housing will privilege some mix of efficiency, neutrality, and representation at the expense of the others. A classical liberal politics worthy of the name will not pretend otherwise. It will argue, explicitly, about where to bend—and keep building institutions that let the people most affected push back when the algorithm’s edge cuts too deep.