Fentanyl Isn’t a Weapon of Mass Destruction. The Drug War Is.

How a Century of Prohibition Turned a Manageable Drug Problem into a Fentanyl-Fueled Mass-Casualty Event

Fentanyl is now officially a “weapon of mass destruction.” On December 15, the president signed an executive order slotting illicit fentanyl and a long list of precursor chemicals into the same conceptual category as nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, and a fact sheet promised a “whole‑of‑government” campaign against this newly christened threat. Television graphics and headlines fell into line, warning that “no bomb” is killing Americans at the rate synthetic opioids are, and treating the announcement as an overdue recognition that the overdose crisis is something like a war we have been losing.

At an emotional level, the move is easy to understand. More than a decade into the opioid crisis, fentanyl and related synthetics now account for a large and rising share of overdose deaths in the United States. Parents bury their children; communities become accustomed to carrying naloxone; public‑health charts begin to look less like snapshots of disease and more like casualty reports. To call fentanyl a weapon feels like moral clarity, an acknowledgment that what is happening is not just tragic but intolerable. Of course, we reach the point where we feel like we have to do something…

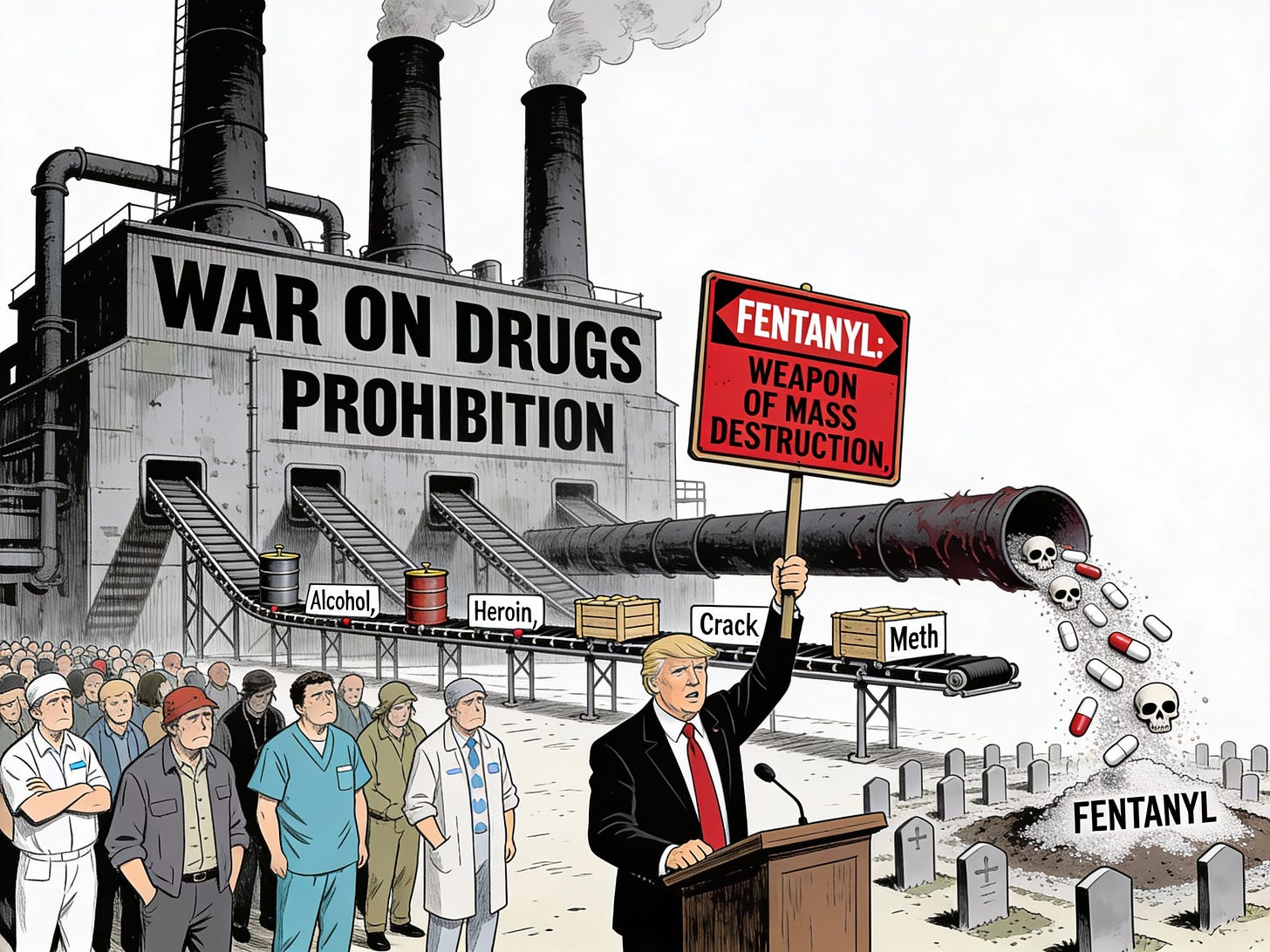

But policy is not therapy (and I know, as I have been in therapy for much of the last year), and in this case the metaphor is not just wrong; it is dangerous. Fentanyl is not an exogenous weapon being wielded against Americans from abroad. It is the predictable, economically rational product of a century‑long experiment with prohibition—a Pygmalion policy that creates what it forbids. If fentanyl now behaves like a weapon of mass destruction, it is because the War on Drugs built the factory in which it is forged.

From Harrison to “Weapons of Mass Destruction”

In some my earlier work at EconLog, I note that the drug war story began not at the border but in the statute book. Laws such as the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act and the Volstead Act did more than restrict certain substances; they inaugurated a paradigm in which the state’s preferred response to disfavored substances was to criminalize them and criminalize the people who used them. As Harrison and Volstead begat the Boggs Act and the Narcotics Control Act, and those in turn begat the modern War on Drugs™, the underlying pattern remained the same: move from regulation and taxation to prohibition and punishment, and then act surprised when violence and black markets follow.

That choice of paradigm dictates the tools. When a substance is treated as an ordinary, if risky, commodity, it is governed by institutions such as the FDA, medical boards, and tax authorities. When it is treated as contraband, it becomes the province of police, prosecutors, and prison wardens. In the former world, the language is that of dosage, purity, contraindications, and externalities. In the latter, it is the language of interdiction, controlled buys, and sentencing enhancements.

Over time, the metaphors used to sustain this regime hardened into reality. Politicians declared a “war on drugs,” and the machinery of the state obliged: we got a drug czar, task forces with military hardware, and legal carve‑outs from longstanding civil‑liberties norms. Civil asset forfeiture turned drug enforcement into a revenue stream—what one of my EconLog posts called “a law enforcement revenue center”—incentivizing agencies to seek out drug cases not simply to reduce harm, but to pad budgets. The Posse Comitatus line blurred as surplus military equipment and training flowed to local police departments, whose tactics in certain neighborhoods began to resemble occupation rather than ordinary law enforcement.

Seen against that backdrop, the decision to label fentanyl a weapon of mass destruction is less a shocking escalation than the logical end‑point of a long rhetorical march: from vice to crime, from crime to war, and now from war to “WMD.” Once you decide that drug use is not just unhealthy or unwise but an attack on the social order, it is only a matter of time before the drug itself is described as an enemy weapon.

The problem is that the facts on the ground tell a different story.

The Iron Law Comes Due

In “Nothing New Thing Under the Sun: Prohibition, Drugs and the Iron Law,” the argument was simple: when the state cracks down harder on a particular drug, the result is not less intoxication but more potency. This is the Iron Law of Prohibition. The more intense the enforcement, the stronger the drugs that survive.

The economic logic here should be obvious to anyone familiar with supply and demand. When interdiction raises the cost and risk of moving drugs, suppliers have every incentive to condense as much “effect” as possible into the smallest possible volume. A gallon of beer is bulky; a gallon of whiskey is less so. A field of opium poppies is visible from the air; a few kilograms of refined heroin can be hidden in a compartment or container. The harsher the enforcement, the more valuable every cubic inch of contraband becomes, and the more the market rewards potency.

History bears this out. Under alcohol prohibition, enforcement did not eliminate drinking; it shifted consumption up the potency ladder from beer and wine toward high‑proof spirits. When late‑twentieth‑century drug enforcement trained its sights on bulky cannabis and powder cocaine, the market responded with crack cocaine and later methamphetamine—cheaper to make, easier to move, and more intense per unit weight.

The opioid crisis follows the same script, only faster. As regulators and law‑enforcement agencies belatedly cracked down on “pill mills” and tightened prescribing guidelines, many dependent users lost access to legally manufactured opioids. They did not, however, lose their dependence. Demand remained, and so the market answered with heroin. Then heroin itself became the focus of interdiction and prosecution, and the stage was set for illicitly manufactured fentanyl and its cousins to enter.

Here again, the empirical work lines up neatly with theory. “US Heroin in Transition” and related research track how shifts in source regions and supply disruptions created openings that fentanyl filled, not because users clamored for it, but because it made economic sense for suppliers operating under prohibition. When heroin purity fell or local supplies became unreliable, cutting or replacing heroin with fentanyl allowed traffickers to restore potency and profits at a fraction of the volume. Analyses of seized drug samples and overdose patterns suggest that law‑enforcement “successes” at removing one supply source are often followed by spikes in fentanyl’s presence and in synthetic‑opioid deaths.

In other words, fentanyl is not some unforeseeable mutation in the drug ecosystem. It is the Iron Law come due. As one public‑health paper puts it succinctly, “today’s fentanyl crisis” is the predictable consequence of the same prohibition dynamics that once pushed drinkers toward bathtub gin.

If policymakers are looking for a “weapon of mass destruction,” they might want to look in the mirror.

Intent, Causation, and the WMD Mirage

The executive order frames fentanyl as a weapon in a very specific sense: a technology being deployed against Americans, primarily by foreign adversaries. Cartels, Chinese chemical exporters, and “narco‑terrorists” fill out the cast of villains. The resulting narrative is familiar from other domains: bad actors abroad manufacture and ship a deadly substance; a besieged America must respond with sanctions, intelligence operations, and perhaps military force.

There is just enough truth in this to make it plausible. Much illicit fentanyl and its precursors do come from outside U.S. borders, and some criminal organizations have clearly used synthetic drugs to increase profits and consolidate power. But the WMD framing invites a profound analytical mistake: it treats the death toll as primarily a function of hostile intent, rather than of the domestic policy regime that structured the market in which those synthetics are profitable.

Most fentanyl‑involved deaths are not the result of deliberate poisoning campaigns. They are isolated overdoses caused by people mis‑dosing a volatile street supply whose potency and composition they cannot reliably know. Users are rarely seeking “fentanyl” as such. Studies of street markets consistently find that fentanyl is often “imposed” on them—mixed into heroin, pressed into counterfeit pills, or substituted entirely—by suppliers responding to supply shocks, enforcement pressure, or simple profit motives. The person who dies on a bathroom floor is not the target of a terrorist plot; he or she is the predictable casualty of a system that has stripped buyers of information and recourse.

There is one dramatic case in which fentanyl‑like agents were used as a literal weapon of mass incapacitation: the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis, in which Russian forces pumped an aerosolized opioid mixture into a sealed building, killing more than a hundred hostages. That incident demonstrates that opioids can be weaponized under specific, controlled conditions. It tells us very little about the dynamics of a diffuse overdose crisis in a country that has chosen to push a large population of drug users into a high‑potency, unregulated market.

If we insist on using the language of weapons, we should at least be honest about who designed the system that made fentanyl the weapon of choice.

Structural Violence in a Synthetic Age

In a 2020 essay bluntly titled “How Structural Violence, Prohibition, and Stigma Have Paralyzed North American Responses to Opioid Overdose,” Mark Tyndall and Zoë Dodd argue that the overdose crisis is best understood as a form of structural violence. People are not simply making bad individual choices; they are operating within a structure that channels certain populations toward harm. Prohibition, they argue, is at the core of that structure.

The criminalization of drug use does more than expose people to arrest. It marks them as legitimate targets for neglect. If using a drug is, by definition, a crime, then the logic of the law suggests that those who do so have voluntarily assumed whatever risks result. In that frame, supervised consumption sites, safe‑supply programs, and even basic harm‑reduction measures like syringe exchanges and naloxone distribution can be cast not as public‑health necessities but as morally suspect “enabling.”

Stigma and law enforcement then reinforce each other. Communities already over‑policed under the War on Drugs—often Black and Brown neighborhoods—experience more surveillance, more raids, and more incarceration. The resulting criminal records make stable employment and housing harder to secure. Poverty and marginalization, in turn, increase vulnerability to problematic drug use and reduce the likelihood that people will seek help from institutions they rightly perceive as hostile. The same neighborhoods, unsurprisingly, have become epicenters of fentanyl‑driven overdose.

The WMD designation does not disrupt this logic; it intensifies it. Once fentanyl is described as a weapon, the people closest to it are no longer neighbors in need of services; they are potential vectors, human shields, or collateral damage. A neighborhood with a high overdose rate becomes, rhetorically, a battlefield. Success is measured not in reduced mortality or improved health, but in seizures, arrests, and the number of “traffickers” neutralized.

If structural violence helped build the fentanyl crisis, it is hard to see how more militarized language and policy will dismantle it.

The Risk Environment We Chose

Public‑health researchers often talk about “risk environments”: the set of social, economic, and legal conditions that make a given behavior more or less likely to lead to harm. The same act can be relatively safe in one environment and deadly in another. Opioid use is a paradigmatic example. Hospitals administer opioids every day with extremely low mortality because dose, purity, and context are controlled. What turns those same molecules into time bombs on the street is the combination of high potency and radical uncertainty.

The American heroin market has undergone what one editorial called a “rapidly changing risk environment” over the past decade. As sources shifted, forms changed (for example, from tar to powder), and enforcement waxed and waned, the composition of drugs sold as “heroin” became more variable. Fentanyl and its analogues crept in first as occasional adulterants, then as more consistent components, and increasingly as the dominant active ingredient.

Law‑enforcement activity folds into this environment as a source of volatility. Seizures and shutdowns of local markets can, in the short run, reduce the availability of specific products. But they also wipe out whatever informal knowledge users have built up about what is available, from whom, and with what typical potency. When a familiar dealer is arrested or a known supply route is disrupted, users are forced to roll the dice on new suppliers and new batches, often with no reliable way to test what they are about to ingest. In a fentanyl‑heavy market, every such forced transition raises overdose risk.

In this sense, the risk environment is not simply an unfortunate background condition. It is something policy has actively constructed. We chose a regime in which a large population of people with opioid use disorder must satisfy that demand through a clandestine market that systematically hides information about potency and composition. We chose, through enforcement priorities, to make that market as volatile as possible, and then we act surprised when volatility plus high potency yields mass death.

It is hard to think of a better description of “structural violence” than that.

A Different Enemy, A Different Response

If the overdose crisis is understood as a war being waged on America by hostile outsiders, then the executive order makes sense: we should treat fentanyl as a weapon, mobilize the national‑security state, and fight back. If, however, fentanyl is better understood as a symptom of prohibition—a downstream effect of the legal and economic architecture described above—then the proper target is not the molecule but the regime that made it inevitable.

That does not mean leaping in one bound from total prohibition to unfettered legalization (although, in my view, this is the end goal). It does mean re‑orienting policy around the question, “What reduces harm?” rather than, “What looks tough?” Evidence from harm‑reduction initiatives points toward a toolbox that looks unglamorous but effective: supervised consumption spaces where overdoses can be reversed on site; drug‑checking services and test strips that tell users whether fentanyl is present and in what concentration; “low‑threshold” access to medications for opioid use disorder; and, more controversially, safe‑supply programs that provide pharmaceutical‑grade opioids to people who would otherwise rely on the street.

Where such measures have been tried, the results have been encouraging. Overdose deaths inside supervised injection facilities are essentially nil. Participants in safe‑supply programs experience fewer overdoses and better overall health, not because opioids have become benign, but because the most lethal features of the illicit market—unpredictable potency and contamination—have been stripped away. Crucially, these interventions do not depend on changing human nature. They assume that some people will continue to seek psychoactive relief and attempt to make that behavior less likely to kill them.

None of this plays well in a WMD frame. Wars are not won by opening supervised consumption sites. Terrorists are not defeated by handing out fentanyl test strips. The more we embrace the language of weapons and enemies, the harder it becomes to sell the public on the small, incremental, life‑saving work that harm reduction requires.

Which leads back to the core claim: fentanyl is not a weapon of mass destruction. Prohibition is. The laws and institutions that criminalize use, profit from enforcement, stigmatize users, and systematically reward ever more potent forms of contraband have created a risk environment in which a substance like fentanyl can cause mass death without anyone ever having to intend a mass killing. The destruction is not being done to us from the outside; it is being done by a system we built and have, so far, refused to dismantle.

Shutting Down the Factory

Recognizing that fact does not instantly tell us what a post‑prohibition world should look like. There are hard questions about how to regulate potent substances, how to balance autonomy with public health, and how to unwind institutions that have built their budgets and identities around fighting a war that never ends. But it does change the question.

If the enemy is “fentanyl,” then the natural response is more of what we are already doing: longer sentences, broader surveillance, more aggressive interdiction, perhaps even military action against producers abroad. If the enemy is instead a policy regime that has proven itself both cruel and ineffective, then the response has to begin at home: decriminalizing possession, rolling back punitive sentencing, cutting off the financial incentives that keep the drug war lucrative for law enforcement, and investing in the mundane work of keeping people alive.

In an earlier EconLog piece, the point was put plainly: drug prohibition increases crime more than drug use does. The same is now true of overdose. The more vigorously we prosecute this war, the more we push the market in the direction of potency, unpredictability, and death. The executive order on fentanyl as a WMD is not a courageous break with that failed strategy. It is an attempt to double down, to rebrand prohibition’s latest and deadliest consequence as an external attack that justifies still more of the same.

If fentanyl is a weapon, the Drug War is the factory. That factory has been humming along for more than a century, steadily refining its output: from alcohol to heroin, from crack to meth, and now to synthetic opioids that can kill with a few milligrams in the wrong place. Shutting it down will be politically difficult, institutionally messy, and morally uncomfortable. But until that process begins in earnest, labeling fentanyl a “weapon of mass destruction” will remain what it is today: not a diagnosis, but a deflection.

FIND MY DRUG WAR SERIES AT ECONLOG AT THE LINKS BELOW

https://www.econlib.org/a-brief-look-at-why-prohibition-laws-dont-work/

https://www.econlib.org/nothing-new-thing-under-the-sun-prohibition-drugs-and-the-iron-law/

https://www.econlib.org/at-what-cost-the-social-costs-of-drug-prohibition/

https://www.econlib.org/blurring-posse-comitatus-the-increased-militarization-of-police/

https://www.econlib.org/civil-asset-forfeiture-the-war-on-drugs-as-a-law-enforcement-revenue-center/

https://www.econlib.org/how-drug-policy-increases-the-rate-of-crime/

https://www.econlib.org/racial-bias-in-drug-enforcement/

https://www.econlib.org/conclusions-and-consequences-abroad/