Classical Liberalism at the Front Line

Why a tradition built on law, markets, and sovereignty cannot shrug at Russia’s war in Ukraine

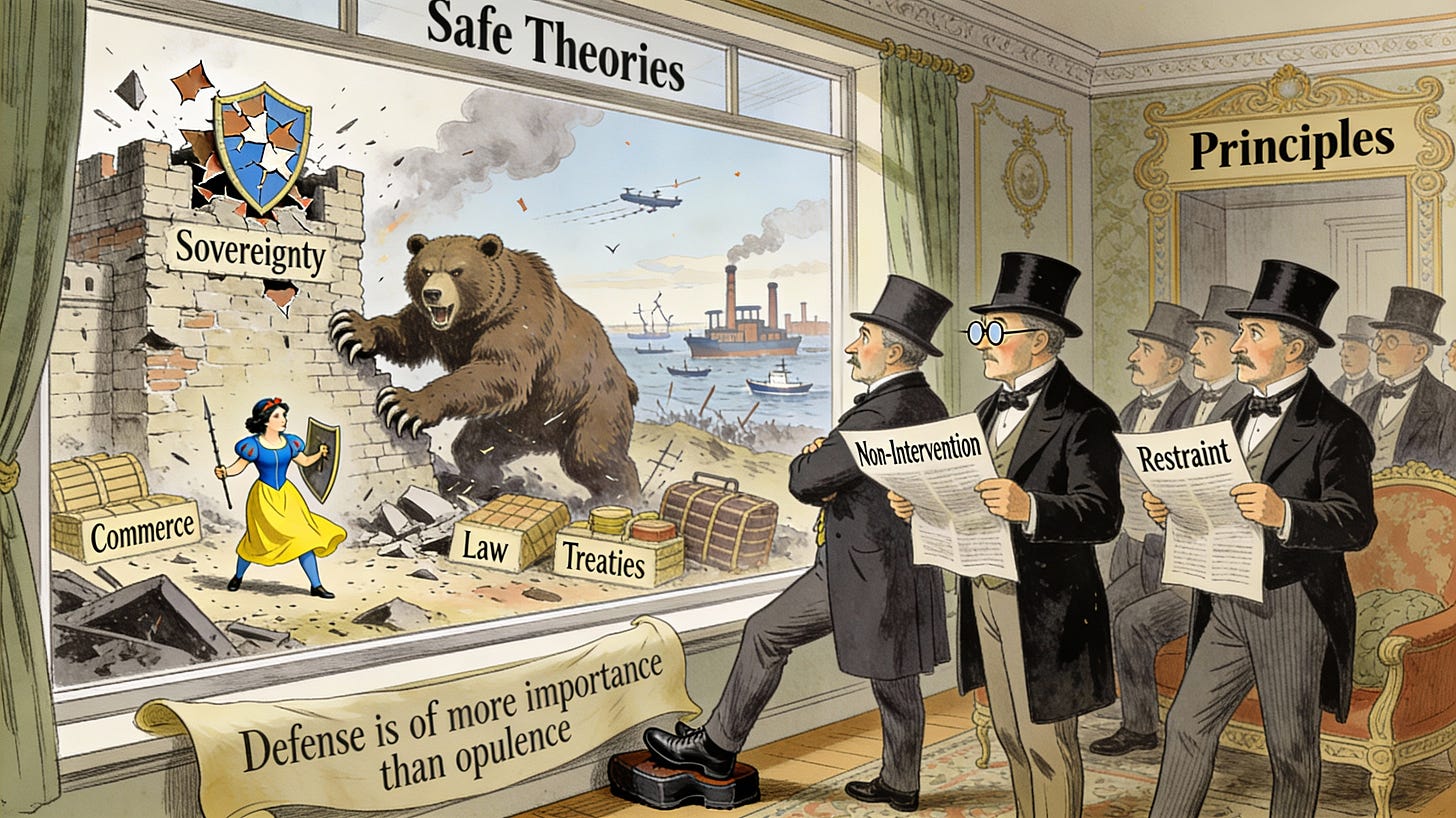

One of the more puzzling developments of the past several years has been watching many self-described classical liberals slide—often unintentionally—into a posture that treats Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a regrettable but essentially external tragedy. The recommended response is typically restraint, distance, and a reflexive invocation of “non-intervention.”

This posture is usually framed as humility. It is presented as realism. Sometimes it is even cast as fidelity to the classical liberal tradition itself. But upon closer inspection, it rests on a selective reading of that tradition—one that mistakes a prudential suspicion of war for a categorical rejection of resistance to conquest, and that quietly assumes that power, once unleashed, will politely stop at borders we decline to defend.

The problem is not merely moral. It is strategic, economic, and institutional. And it is precisely on these grounds—grounds laid by Adam Smith, Francisco de Vitoria, Hugo Grotius, and their intellectual descendants—that modern non-interventionist classical liberalism begins to look less like wisdom and more like a dangerous simplification.

Classical Liberalism Was Never Pacifism

Classical liberalism emerged not in a world of benign commerce and stable borders, but in one of imperial rivalry, dynastic war, mercantilist monopolies, and endemic coercion. Its central project was not the abolition of power, but its domestication: the channeling of force through law, institutions, and norms so that liberty and commerce could survive.

Adam Smith is often invoked as the patron saint of peaceful exchange, and rightly so. But Smith never believed that markets float free of politics or that trade can flourish without security. In The Wealth of Nations, he famously insisted that “defense… is of much more importance than opulence.” That statement is not a rhetorical aside. It is an admission that the conditions of prosperity—contract, property, investment, insurance, shipping—are not self-enforcing. They are protected.

Smith opposed wars of vanity and mercantilist adventurism. He did not oppose defensive wars, nor did he imagine that free trade could be sustained if strategic chokepoints, ports, and trade routes fell under the control of powers willing to weaponize them. A state that allows conquest to proceed unchecked does not preserve peace; it defers conflict and raises its eventual price.

Modern empirical work reinforces Smith’s intuition. Research from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank consistently shows that conflict risk reduces trade flows and investment and raises the cost of capital—especially when wars threaten ports, energy infrastructure, and transportation corridors. Markets can be remarkably adaptive, but adaptation is not the same as indifference. A war that reliably increases risk and uncertainty is, by definition, a war that taxes commerce.

In other words: even on cold economic terms, a rule of “non-intervention” cannot be treated as a timeless first principle. It is a rule of thumb—useful when the world is stable, dangerous when it is not.

Vitoria, Grotius, and the Moral Architecture of Sovereignty

If Smith explains why commerce depends on security, Vitoria and Grotius explain why the security question is not merely a contest of force. It is a contest of legitimacy. Francisco de Vitoria articulated a doctrine of sovereignty grounded not in divine right or imperial ambition, but in natural law. States possess legitimate authority over their territory and people, and war is just only in response to injury. Conquest, historical claims, ethnic destiny, and civilizational missions do not suffice.

Those principles map cleanly onto modern international law, most notably the United Nations Charter, which prohibits the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of states. And contemporary legal commentary has repeatedly stressed that Russia’s stated rationales do not satisfy the legal standards for self-defense under the Charter.

For a careful overview, see the American Society of International Law’s analysis on why the invasion violates core legal norms. This matters because classical liberals are not simply enthusiasts for peace; they are enthusiasts for a moral and legal order that restrains violence.

Hugo Grotius extended this framework into what became the foundation of the law of nations. Aggressive war, he argued, is a crime not merely against the immediate victim, but against international order itself. Treaties bind. Borders matter. Sovereignty cannot be nullified by force without dissolving the conditions under which states coexist.

Grotius is especially relevant to today’s debate because he rejected the comforting idea that injustice may be ignored so long as it is distant. A system that tolerates conquest invites its repetition. Law without enforcement is not restraint; it is performance. And the performance ends the moment a sufficiently motivated aggressor decides the props are fake.

This is why the classical liberal suspicion of war does not automatically translate into a classical liberal obligation to neutrality. In the older tradition, assisting a victim of unjust aggression can be consistent with both morality and law—especially when the alternative is to normalize conquest.

Ukraine and the Economics of Power

The economic stakes of the war in Ukraine are often understated by non-interventionists who treat it as a tragic but localized conflict. In reality, Ukraine sits at the intersection of global grain markets, energy transit corridors, and the security architecture of the Black Sea region.

Ukraine has historically been among the world’s most significant exporters of wheat, corn, and sunflower oil, and disruptions have had measurable global effects—particularly for food-importing regions—as documented by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Control over southern and eastern Ukraine shapes access to ports, shipping lanes, and regional chokepoints. The Black Sea is not a peripheral theater. It is a conduit for trade linking Europe, the Middle East, and beyond. A Russia that consolidates control over this region gains leverage not only over Ukraine, but over neighboring states and global markets. You do not have to romanticize geopolitics to notice that trade routes become political when a revisionist power can threaten them.

And here is the part many non-interventionists glide past: the strategic value of territory is not limited to what you can extract from it today. It includes what you can deny others tomorrow. A country’s ports are not just commercial assets; they are strategic options. A country’s coastal access is not just a matter of exports; it is a matter of whether the state can remain economically viable under pressure.

Smith’s commercial society depends on predictable rules. Conquest rewrites rules by force. And force, unlike law, has a habit of expanding until it is stopped.

Missile Escalation and the Myth of a “Frozen” War

A common refrain among non-interventionists is that the war has “settled” into stalemate and that additional Western support only risks escalation. This claim is increasingly difficult to square with reality, especially when one looks at the war’s long-range strike dynamics.

Russia’s large-scale missile and drone campaigns—often aimed at energy infrastructure, civilian areas, and port facilities—have been analyzed as deliberate attempts to degrade Ukraine’s economic viability and to impose political pressure through fear and exhaustion. See, for example, CSIS on Russia’s missile campaign and RUSI on strikes against Ukraine’s energy system.

Missile warfare also has a signaling function. High-speed systems, saturation attacks, and repeated strikes on civilian infrastructure are not merely tactical decisions; they are communications. They say: we can keep doing this. We can raise the cost. We can test your air defenses, strain your interceptors, and measure your political stamina.

Strategic analysts at the International Institute for Strategic Studies have repeatedly emphasized that long-range strike campaigns are about more than battlefield shaping; they are about coercion and endurance. From a classical liberal perspective, the point is not to become fascinated with hardware. The point is to recognize that modern coercion often arrives by missile rather than by cavalry.

This matters because escalation is not avoided by passivity. It is shaped by expectations. If an aggressor learns that escalating pressure yields political concessions, pressure becomes the policy. The war does not freeze; it evolves.

The Strategic Error of Mechanical Non-Intervention

Modern non-interventionist classical liberals often present their position as a rejection of hubris. They warn against entanglement, escalation, and the moral hazards of state action. These concerns are not frivolous. They deserve to be taken seriously.

But they become untenable when non-intervention is elevated from a prudential guideline to an inviolable principle. Classical liberalism does not teach that all interventions are equal. It teaches that power must be justified, limited, and accountable. There is a categorical difference between wars of choice and wars of resistance; between empire-building and deterrence; between coercion and assistance requested by a sovereign state fighting for survival.

Ukraine is not asking the United States or its allies to conquer on its behalf. It is asking for the means to resist conquest. That distinction matters. It is the difference between helping preserve a legal order and helping dismantle one.

This is also the logic behind deterrence arrangements: not because they guarantee peace, but because they reduce the probability of war by raising the expected cost of aggression. NATO’s public material on deterrence and defense captures the basic idea. Deterrence is not a confession of militarism; it is an attempt to prevent militarism from paying.

A mechanical non-interventionism assumes that staying out is always the least risky option. In reality, it often transfers risk into the future—where it compounds. If a revisionist power can redraw borders by force at tolerable cost, the incentive structure changes. Small states arm. Large states bargain with threats. Everyone pays higher insurance premiums.

The Spillover Problem: Belarus, Georgia, and the Logic of Permission

To say that Ukraine’s fate affects its neighbors is not to predict inevitable invasion. It is to recognize patterns of coercion. Belarus has already functioned as a platform for Russian military pressure, and Georgia has experienced territorial dismemberment and ongoing intimidation. The relevant claim is not that every neighbor is “next.” The relevant claim is that success in Ukraine strengthens a model of revisionism that can be applied elsewhere—through military action, subversion, or coercive diplomacy.

Grotius would have recognized this dynamic immediately. The normalization of territorial seizure alters expectations. It raises the baseline risk for all states, especially small ones, and encourages arms races and preemptive behavior. The result is not peace, but a more militarized and unstable world.

The Dollar, Sanctions, and Financial Fragmentation

Some critics argue that supporting Ukraine accelerates de-dollarization and undermines the international financial system. The concern is not entirely misplaced. Sanctions do create incentives for diversification, especially for states that fear becoming targets. Financial fragmentation is real.

But the evidence suggests gradual change rather than imminent collapse. The IMF has discussed the durability of dollar dominance alongside modest diversification trends—see, for example, its work on the international currency system. Meanwhile, the Bank for International Settlements regularly highlights how market depth, liquidity, and institutional trust sustain reserve-currency status.

A world in which conquest is rewarded is not a safer monetary world. It is one in which contracts, currencies, and commitments are politicized anyway—just by force rather than law. Classical liberals should be more worried about an order where coercion becomes normal than about the marginal portfolio adjustments of central banks.

Engaging Modern Non-Interventionists Directly

At this point, the modern non-interventionist will often insist: you are building an argument that can justify anything. Once you concede that some wars are worth supporting, you open the door to endless “exceptions.” And once you open that door, the state will walk through it—claiming necessity, invoking security, and eroding liberty at home.

This is not a straw man. It is a serious concern, rooted in a sober reading of history. States have exploited foreign threats to justify domestic repression. Bureaucracies expand in wartime. Emergency measures become permanent. And humanitarian rhetoric can be weaponized for moral cover.

But notice what follows if we accept this concern as decisive: we would never resist conquest anywhere, because resistance always has costs. We would treat every strategic challenge as a trap, because politics is always imperfect. We would reduce classical liberalism to a posture of abstention—a doctrine that cannot distinguish between empire and defense, between predation and protection, between a war of choice and a war forced upon a free people.

Classical liberalism is better than that. It is not a theology of non-action. It is a practical philosophy of constrained power. The question is not whether power will exist; the question is whether it will be constrained by law and directed toward defensible ends.

If we cannot tell the difference between assisting a sovereign democracy fighting for survival and launching discretionary wars for regime change, then we have not achieved prudence. We have achieved a moral and strategic blur.

Steelman: The Best Case for Non-Intervention

Let me put the non-interventionist case in its strongest form.

First, escalation risk is real. Great-power conflicts can spiral. Nuclear threats, miscalculation, and crisis instability are not academic abstractions. Second, the opportunity cost is real. Every dollar spent abroad is a dollar not spent on domestic priorities—economic mobility, institutional repair, and fiscal stability. Third, there is an institutional risk: wartime politics tends to expand executive authority, empower security bureaucracies, and corrode the liberal habits that classical liberals rightly cherish. Fourth, there is a knowledge problem: outsiders routinely misunderstand local dynamics, overestimate their leverage, and stumble into commitments they cannot control. Finally, there is the “where does it stop?” problem: support today becomes obligation tomorrow, and a limited mission metastasizes into open-ended responsibility.

If classical liberals cannot take these concerns seriously, then they are not thinking in a classical liberal register. They are thinking in slogans.

Rebuttal: Why the Steelman Still Fails

Now the rebuttal—still in classical liberal terms.

Escalation is not avoided by default; it is managed. The relevant question is not “Can escalation happen?” The question is “What choices reduce the likelihood that escalation pays?” A strategy that signals weakness in the face of coercion may reduce immediate friction while increasing the aggressor’s confidence. If coercion produces concessions, coercion becomes rational.

Opportunity costs are real, but so are deferred costs. A Europe destabilized by successful conquest is not free. It requires higher defense spending, greater political risk, disrupted trade, and intensified energy insecurity. Classical liberals should care about the long-run fiscal and economic burden of a world where aggression is profitable.

The institutional risk is real, and it is precisely why support for Ukraine should be designed in ways that minimize domestic liberty costs: transparent budgeting, congressional oversight, clear objectives, and a refusal to treat “security” as a blank check. The appropriate classical liberal response to the risk of state expansion is not to abandon victims of aggression. It is to constrain the state at home while pursuing defensible ends abroad.

The knowledge problem is real, but it is not symmetrical. We do not need perfect knowledge to distinguish aggression from defense. We do not need omniscience to see that annexation by force undermines the law of nations. And we do not need to micromanage Ukraine to recognize a legitimate request for assistance.

As for “where does it stop?”—that question also applies to neutrality. If conquest is rewarded once, why stop there? If coercion works, why not use it again? The stopping point is not guaranteed by abstention. It is established by credible resistance.

Conclusion: The Cost of Forgetting Power

Classical liberalism does not require passivity in the face of conquest. It requires resistance to it—because liberty, markets, and law cannot survive where force is rewarded.

The tragedy of Ukraine is not only that a sovereign nation has been invaded. It is that a strand of liberal thought has forgotten its own foundations. Classical liberalism arose as a response to domination, not as a retreat from responsibility.

If conquest is allowed to succeed because resisting it is deemed too risky, too costly, or too impure, then the lesson absorbed by the world is not one of peace, but of permission. And permissions, once granted, are rarely revoked.