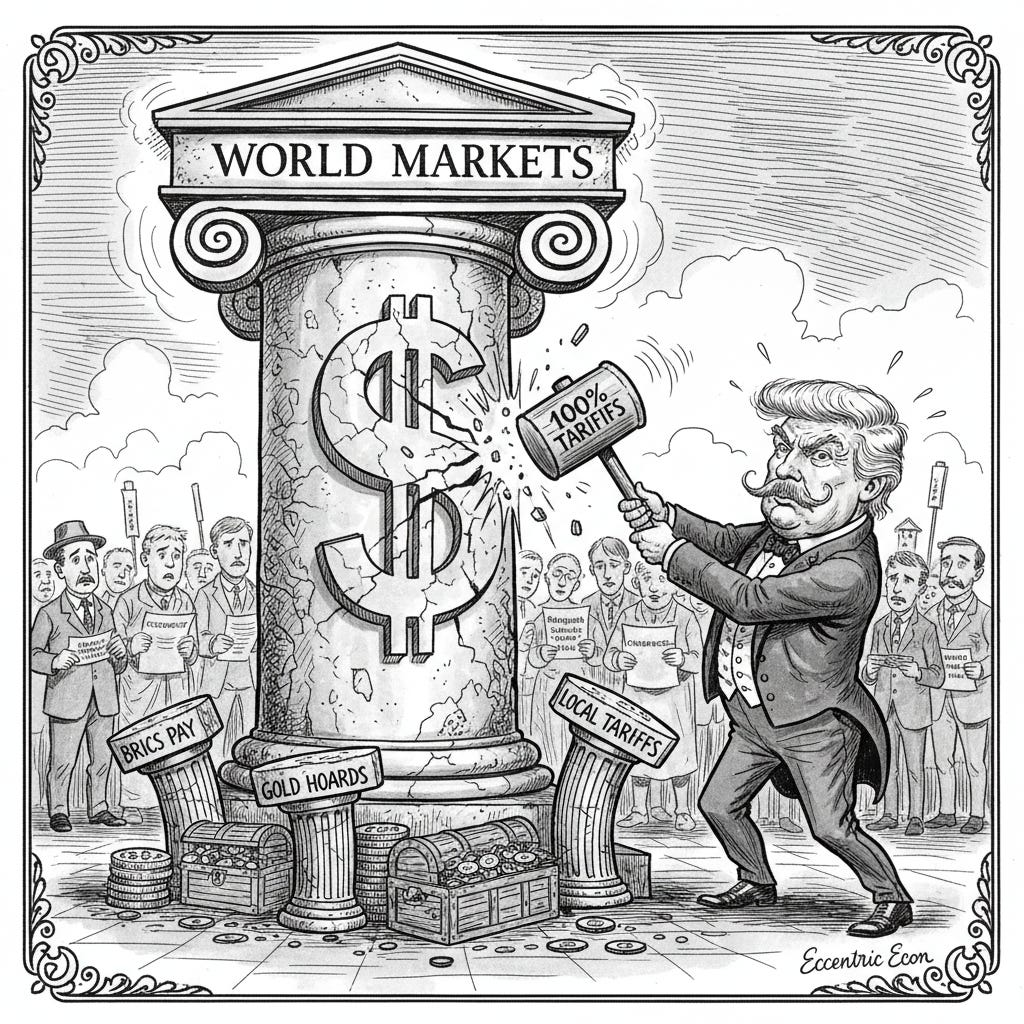

BRICS Mirage: Why Dollar Hegemony Endures, Trump’s Tariff Threats Miss the Point, and Attacking BRICS Backfires

BRICS de dollarization makes great television. As a real threat to U.S. monetary power, it’s mostly theater—and the loudest American response so far risks doing more damage than the problem it claims

I was talking to a couple associates of mine – not economists, mind you, but folk who actually work for a living -and they had some strong opinions on, of all things, BRICS. At first, I rolled my eyes because I couldn’t figure out why, and then it came to me; If you take Donald Trump at his word, the future of the dollar now hinges on how hard Washington is willing to swing a tariff hammer.

In late 2024 and early 2025, Trump vowed that any BRICS country that “even thinks” about creating a rival currency or shifting away from the dollar will face 100 percent tariffs on its exports to the United States. The message on Truth Social was unambiguous: pledge allegiance to “the mighty U.S. Dollar,” or “say goodbye” to the U.S. market. Since then, the threat has metastasized into a standing promise of at least 10 percent tariffs on countries that “align” with BRICS.

You do not roll out that kind of language for a marginal issue. You roll it out when you think the foundation is cracking under your feet.

The problem is that the foundation—while far from perfect—simply is not cracking in the way Trump says it is. As of early 2026, the dollar still anchors roughly 58 percent of global foreign‑exchange reserves, about 54 percent of export invoicing, and nearly 88 percent of FX transactions. The euro is a distant second at around 20 percent of reserves, with the yen, pound, and renminbi scraping together single‑digit shares. Even the recent slippage in the dollar’s share—from the low 60s to the high‑50s range—looks a lot smaller once you adjust for valuation effects, something the IMF has quietly noted in its reserve data.

Dollar dominance is not costless, and it is not guaranteed forever. BRICS‑style de‑dollarization is one of several slow‑moving forces pushing the world toward something more multipolar. But if you were designing an order in which the greenback gradually lost pride of place, you probably wouldn’t start with a club of countries that do not trust one another’s statistics, much less one another’s central banks.

You also wouldn’t respond to their hedging by advertising to half the planet that the United States is now so anxious about currency competition that it is willing to tax their exports into submission.

From a classical liberal perspective, that is the more serious problem. The immediate question is not whether BRICS can “kill” the dollar. It is whether U.S. policymakers will panic their way into responses that make a slower erosion of trust more likely.

What BRICS Is Actually Doing

To understand why the panic is overblown, it helps to distinguish between the rhetoric and the plumbing.

On the rhetoric side, BRICS officials and sympathetic commentators talk about building an alternative Bretton Woods: a BRICS “unit” currency potentially backed by a basket of member currencies and commodities, a parallel network of institutions like the New Development Bank and Contingent Reserve Arrangement, and a concerted push to settle trade in local currencies rather than dollars. At the 2024 Kazan summit and again in 2025, leaders floated plans for a “BRICS Pay” messaging and payments system, meant to route around Western‑dominated infrastructure like SWIFT.

On the plumbing side, the reality looks far more incremental.

Russia and China have shifted much of their bilateral trade into yuan to dodge sanctions and reduce dollar exposure.

India has experimented with rupee payments for Russian oil, with mixed uptake.

Brazil and China have set up local‑currency settlement arrangements to reduce dollar demand in their trade.

The New Development Bank does a rising share of its lending in non‑dollar currencies, explicitly in the name of reducing dollar dependence.

As Peter C. Earle notes in his overview of BRICS 2025: Expansion, De‑Dollarization, and the Shift Toward a Multipolar World at The Daily Economy, these steps add up to more than symbolism: expanded membership, gold accumulation, and plumbing projects like BRICS Pay give the bloc more options than it had a decade ago. They nibble at the edges of a system that has taken the dollar’s centrality for granted.

But the key word there is “edges.” Even Earle’s generally sympathetic treatment acknowledges that much of the agenda remains aspirational, and that internal contradictions—economic, political, and strategic—keep BRICS a long way from offering a full‑spectrum alternative.

BRICS intra‑bloc trade still makes up only about 15 percent of members’ total trade, and the New Development Bank’s balance sheet, in the tens of billions, is tiny next to the trillion‑plus firepower of institutions like the IMF. The idea of a full blown BRICS currency remains, for now, a talking point rather than a treaty.

In that sense, BRICS is better understood as a hedging vehicle inside an already dollar‑centric system, not as a replacement for it.

The Dollar’s Uncomfortable Advantages

Saying that BRICS is not an imminent threat is not the same as saying the dollar has no problems. It is saying that the bar for replacing—or even meaningfully displacing—the dollar is extraordinarily high.

Reserve currencies are held not just because their home economies are big, but because they offer a combination of:

Deep, liquid financial markets.

Convertibility and open capital accounts.

Legal and institutional protections that give investors confidence.

On those fronts, the dollar retains three uncomfortable advantages.

First, the U.S. still offers the deepest, most liquid market for high‑quality sovereign debt in the form of Treasuries. Even with higher yields and rising debt‑to‑GDP, those securities remain the default safe asset for much of the world.

Second, the legal and political environment—while clearly more volatile than it was twenty years ago—still looks predictable compared with authoritarian alternatives. Foreign investors may not love Congress, but they generally trust U.S. courts more than courts in Beijing or Moscow.

Third, the alternatives remain under‑developed. The euro is bogged down by fragmentation and unresolved questions about fiscal union. The renminbi is constrained by capital controls and a legal system where politics can trump contract law. A synthetic BRICS unit, if it ever comes into being, will have to overcome not just technical hurdles but deep, mutual suspicion among member governments.

That helps explain why, as Earle emphasizes in another widely shared piece—Dollar’s Decline Meets Rising Dedollarization: The Threat Comes from Within—“dollar weakness and de‑dollarization are not synonymous.” The Bloomberg Dollar Index can fall nearly nine percent, gold purchases by central banks can surge past 1,000 tons a year, and investors can rotate into higher‑yield emerging‑market currencies—without that necessarily adding up to a structural dethroning of the dollar.

True de‑dollarization, as he points out, “requires the sustained development of viable alternatives that can match the dollar’s liquidity, legal protections, and institutional depth—an outcome that remains distant, though not unimaginable over the long term.” That is the background against which Trump’s tariff theatrics should be judged.

Trump’s “Tariff Shield” for the Dollar

Trump’s core proposition is simple: if BRICS countries want to play games with currency, they can “say hello to tariffs and goodbye to America.” In his telling, the threat of a 100‑percent levy is a blunt but necessary tool to protect U.S. workers, punish “anti‑American” coalitions, and defend dollar primacy.

If your model of global finance is a zero‑sum wrestling match, this kind of posture has a certain intuitive appeal. Punish defectors. Make an example of them. Remind smaller economies that access to the U.S. market is contingent on good behavior.

As a macro strategy, though, it is almost perfectly backward.

When economists at the Peterson Institute modeled a hypothetical 100‑percent tariff on imports from BRICS countries, they found that by 2029, U.S. GDP would be roughly $430 billion smaller than it otherwise would be, with inflation about 1.6 percentage points higher as higher import prices ripple through the economy. BRICS members would take substantial hits as well, but the tariffs are hardly a free lunch for American households or firms.

More importantly for the de‑dollarization debate, those tariffs would reshape trade and financial flows in exactly the direction Trump says he fears. If shipping into the U.S. becomes politically precarious and permanently more expensive, then building out alternative markets and payment networks stops being a boutique project and becomes a strategic necessity.

Earle’s own BRICS survey makes that logic explicit. He warns that “the threat of substantial tariffs, such as the proposed 100 percent levy on imports from BRICS nations, could incentivize these countries to expedite efforts toward de‑dollarization and the development of alternative financial systems,” precisely so they can “insulate their economies from US economic policies and potential sanctions.” The more loudly Washington advertises its willingness to weaponize both tariffs and the dollar, the stronger the incentive becomes for governments—especially in the Global South—to reduce exposure on both fronts.

In that sense, Trump’s threats are not a shield for the dollar. They are an open invitation for rivals and fence‑sitters to invest more heavily in end‑runs around the U.S.-centric system.

How to Actually Undermine Dollar Hegemony

If you were trying to script the gradual erosion of dollar dominance from the inside, you might lay out a sequence something like this:

Politicize your central bank, attacking its independence whenever it tightens policy in ways the White House dislikes.

Run persistent fiscal deficits and signal little appetite for reform, making long‑term debt dynamics look increasingly shaky.

Use sanctions and export controls so broadly that even friendly governments start to see the dollar as a vulnerability.

Turn access to the U.S. market into a discretionary favor, threatening sweeping tariffs over everything from steel imports to currency choices.

The uncomfortable reality is that American politics has been checking boxes on that list for years, and Trump’s BRICS crusade simply extends the pattern into a new theater.

In his de‑dollarization essay, Earle drives home the point in a way that should resonate with classical liberals: “The greatest threat to continued dollar dominance comes not from external challengers but within.” Persistent fiscal indiscipline, rising debt‑to‑GDP ratios, erratic trade and foreign‑policy shifts, and the politicization of monetary and financial institutions all “erode the confidence that anchors reserve currency status.”

Where Earle is right is in treating BRICS de‑dollarization as a symptom of a fraying monetary order rather than its cause. Where his analysis invites sharpening is in the political economy: the decisive variable is not what happens at BRICS summits in Kazan or Johannesburg, but what happens in Washington—at the Fed, in Congress, and in a White House that increasingly treats the dollar like a cudgel.

From that vantage point, obsessing over the technical details of BRICS Pay looks like a category error. The most powerful way to weaken the dollar is not to invent a rival currency basket in Shanghai. It is to convince markets that the U.S. has lost interest in being a predictable steward of the system it built.

Why Attacking the BRICS Arena Backfires

The classical liberal case for a dollar‑centric system is not that the U.S. “deserves” tribute. It is that a world organized around a single, reasonably stable, widely accepted unit of account makes trade cheaper, contracts clearer, and investment less risky—even when that unit is imperfect and occasionally abused.

In that frame, the sensible response to BRICS experiments is boring:

Keep your fiscal house in better order than your rivals.

Protect central‑bank independence, even when higher rates are politically painful.

Use sanctions sparingly and predictably, anchored in law and alliances rather than impulse.

Deepen trade and security ties so that holding dollars feels safe because the U.S. feels safe as a partner.

Trump’s approach flips this logic. By turning currency choice into a loyalty test—“use our money or face our tariffs”—he validates the core BRICS narrative that the dollar is less a neutral platform and more an instrument of domination. By portraying every local‑currency settlement or payment pilot as a kind of economic treason, he raises the political returns on building alternatives that might otherwise have remained marginal hedges.

Once you normalize the idea that the U.S. will slap large, across‑the‑board tariffs on trade over financial policy disagreements, you teach the rest of the world three lessons:

Access to the U.S. market is a contingent privilege, not a predictable, rule‑governed framework.

Domestic financial policies—even those that do not directly target the U.S.—are fair game for coercive leverage.

Any country large enough to matter needs an exit strategy from a purely dollar‑centric system.

Seen from Brasília or Riyadh, that is not a reason to double down on the greenback. It is a flashing neon sign over the exit.

The Real Work of Preserving Dollar Primacy

Strip away the theatrics, and the project of preserving dollar primacy is an exercise in institutional maintenance.

It looks like letting an independent Federal Reserve say “no” to the White House when the political temptation is to demand easier money. It looks like doing the slow, unpopular work of putting the U.S. on a more sustainable fiscal path, so that Treasury bonds remain the world’s preferred collateral rather than a reluctant compromise.

It looks like calibrating sanctions so they remain a powerful, credible tool for punishing genuine aggression and corruption, instead of a reflexive response to every diplomatic slight. It looks like treating allies in Europe and Asia as partners in managing a shared monetary system, not as vassals to be threatened with tariffs whenever a president wants to look tough.

Above all, it looks like resisting the urge to turn every structural question into a television‑ready showdown. BRICS de‑dollarization is, for now, a marginal shift in how a specific set of countries handle some of their trade and reserves. It is worth tracking; it is worth debating; it is not worth detonating America’s reputation as a predictable hegemon over.

There is a legitimate conversation to be had about whether the world should, over time, move toward a more plural currency landscape—one where the dollar shares space with a stronger euro, a more open renminbi, and perhaps a handful of regional units. There is an equally serious debate about whether the U.S. would actually be healthier in the long run with slightly less “exorbitant privilege” and slightly more budgetary discipline.

But those are debates for legislatures, central‑bank boards, and long‑horizon investors—not for all‑caps threats on social media.

BRICS, as currently constituted, is not in a position to topple the dollar. The more plausible danger is that American policymakers will react to modest hedging abroad by behaving in ways that make a genuine exit from the dollar system look more attractive than it has any right to be.

A liberal monetary order is sustained by consent and credibility, not by daring smaller countries to “say hello to tariffs.” If the U.S. wants to keep the privileges that come with issuing the world’s balance sheet, it should spend less time shadow‑boxing with the BRICS mirage—and more time making sure the real threat to the dollar does not keep coming from within.